Greater Philadelphia Region

Essay

Variously defined as key elements of its identity have shifted over time, the Greater Philadelphia region has been an especially dynamic and unusually fragmented entity compared to other U.S. metropolitan areas. The region not only crosses multiple state lines; it is further divided into hundreds of extremely small communities, many of which date back to the colonial era. Although that formal fragmentation barely changed across the centuries, informal connections among residents reached across town boundaries, gradually building webs of regional relationships based on economic and transportation connections that linked producers to markets, workers to jobs, and households to churches, stores, and taverns. As those every-day connections multiplied across county and township lines, the fragmentation of governmental authority posed substantial obstacles to coordinated planning for the region–leading citizens to rely on nongovernmental organizations to span the governmental boundaries that subdivide the region.

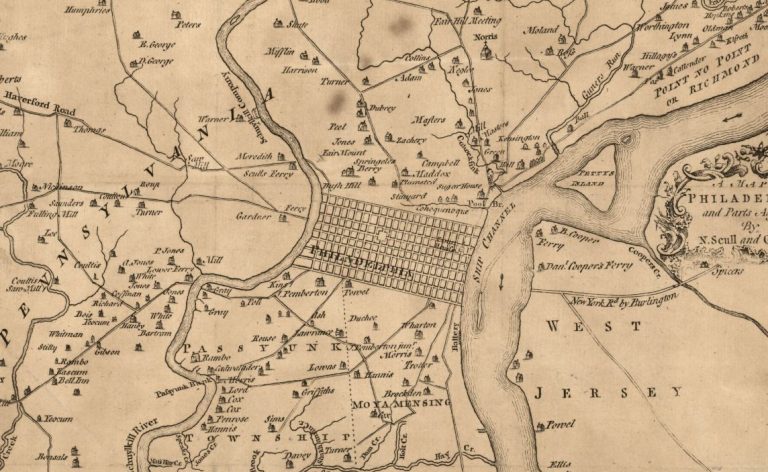

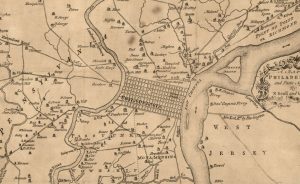

Natural features shaped the territory’s historical development. A range within the Appalachian Mountains separated the Atlantic coastline from the interior woodlands, stretching from northeast to southwest. The mountains’ long, even ridges, with deep valleys in between, presented an important obstacle to east–west land travel. This meant that the region’s early residents were better connected to other East Coast communities than to the interior, because of the difficulty of traveling across mountainous barriers.

The river system also exerted strong influences on human settlement. That system centered on the Delaware River flowing south from the Catskill Mountains. Several primary tributaries fed from the north and west into the Delaware River: the Lehigh River originating between ridges of the Appalachian Mountains, the Schuylkill River flowing from what later became the city of Reading, and the Brandywine River flowing from the Welsh Mountains in northern Chester County southeast into the Delaware River at the location where Europeans built the city of Wilmington.

The historic homeland of the indigenous Lenape people crisscrossed the entire Delaware River system, creating a complex pattern of overland paths leading to commonly-used locations to ford the rivers and streams. The Delaware River symbolized the regional unity among the Lenape, who explained to the European newcomers that “we reckon ourselves all one, because we drink one water.”

Europeans shattered that regional unity by subdividing the Lenape homeland into separate provinces, counties, and townships and establishing patterns of government that descended down to the twenty-first century. Dutch and Swedish trappers and timber merchants initially visited the territory on the eastern bank of the Delaware River in the 1600s, but they were displaced by British settlers in the 1660s when Britain’s King Charles II (1630-1685) granted the proprietorship of the colony to his brother James (1633-1701). James attracted Quakers to settle in Salem and Burlington and named the area after the isle of Jersey in Britain. In 1674 New Jersey was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey, two distinct provinces of the proprietary colony (a division that was soon reversed in 1702).

William Penn’s Grant

To develop the territory on the western bank of the Delaware River, Britain’s King Charles II in 1681 granted the province of Pennsylvania to William Penn (1644-1718), who also attracted Quakers and other religious nonconformists to the New World. William Penn’s land grant from the British Crown encompassed what eventually became the state of Pennsylvania. In addition, Penn acquired land farther south on the Delaware, but his rule there was only short-lived, ending in 1704 when the settlers broke away from Penn to form the Lower Counties of Delaware.

Using the river as the boundary dividing western New Jersey from Pennsylvania and Delaware, European settlers began creating county boundary lines, and in some instances subdividing those original counties as, for example, when Lancaster County was carved out of Chester County in 1729, and when Berks County was created from parts of Philadelphia, Chester, and Lancaster Counties in 1752. Well after the American Revolution had formally established state boundaries, citizens continued subdividing territory to create new county units like Montgomery County, Pennsylvania (carved out of Philadelphia County in 1784); Delaware County, Pennsylvania (carved out of Chester County in 1789); Mercer County, New Jersey (carved out of Somerset and Middlesex Counties in 1838); and Camden County, New Jersey (carved out of Gloucester County in 1844).

Below the county level, William Penn fervently supported the formation of small towns that could practice direct democracy to conduct local affairs. For example, most of the townships in Delaware County were originally incorporated before 1700. Already-small townships became even smaller wherever residents successfully petitioned the state to carve boroughs out of existing townships. Some settlers favored boroughs because, unlike townships, boroughs provided some public and commercial facilities like docks, weighing stations, and constables who could settle disputes and keep the peace in the area. Many of the townships in Montgomery County were incorporated in the eighteenth century, with boroughs carved out in the nineteenth century. That pattern was repeated in Bucks and Chester Counties.

New Jersey also adopted small townships, measured by both land area and population. By 1776, the entire state of New Jersey had been divided into thirteen counties, eight of which were ultimately sub-divided into smaller counties, which in turn were split into townships. Many of those early townships were further subdivided, sometimes reflecting political disputes, but most often to ensure that local farmers and merchants controlled road development and maintenance in their vicinity. From the 1840s through the 1920s, New Jersey incorporated a handful of new municipalities every year, often due to complaints that an existing local government was not responding to specific concerns. In some cases, residents in one part of town simply resisted spending for streets and sewers in other parts of town, thus leading to separation and creation of new municipalities.

Early Settlement Patterns

Early settlers immigrated mainly as farmers, turning both sides of the Delaware River into landscapes of scattered farmsteads that produced agricultural products and livestock. The main cultural groups populating Pennsylvania during the colonial period were the English (who predominated in the city of Philadelphia and townships closest to its borders); Germans (in the northern section of Bucks County and what became Montgomery County, as well as Lancaster County); the Scots-Irish in Chester County; and the Welsh on the northern border of Delaware County. In colonial West Jersey, William Penn’s influence assured the dominance of English Quakers among early colonists. The lower colonies on the Delaware—later the state of Delaware—first settled by Scandinavian Lutherans and Dutch Reformed, subsequently attracted English Quakers and Welsh Baptists. In the eighteenth century, Delaware became increasingly British, with the Church of England gaining adherents before the American Revolution. In all parts of the tri-state region, religious dissenters like Quakers and Mennonites settled in sizable numbers, lured by Penn’s promise of religious freedom.

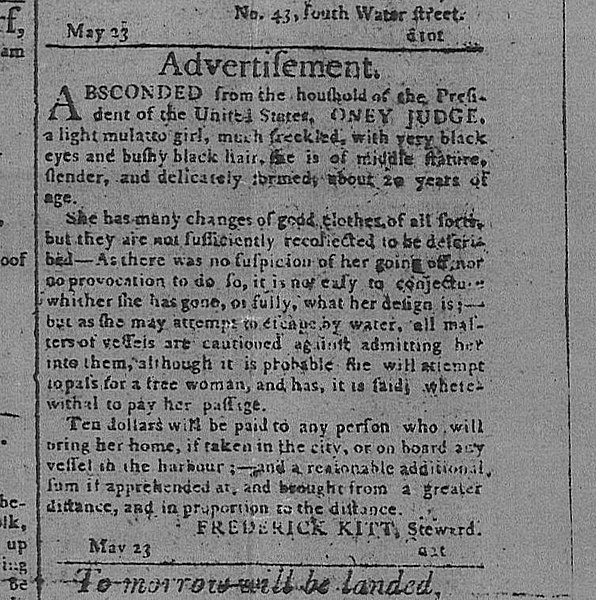

People of African descent arrived with the region’s earliest European settlers as enslaved laborers as early as 1639, although they were few in number. The first slave ship to arrive in Philadelphia, in 1684, brought 150 slaves into a population of about two thousand. Often arriving from previous bondage in the Caribbean, the enslaved filled many labor needs in the region’s diverse economy. Pennsylvania settlers’ preference for growing wheat on small farms meant they had a limited need for slaves, but Delaware growers cultivated more labor-intensive crops like tobacco and corn. Philadelphia, never as reliant on the institution as New York City, fostered slavery along with indentured servitude for most of a century until the enslaved population reached a peak of about one thousand on the eve of the Revolution. By 1783, however, the enslaved population had dropped to under 450 people, while the number of free Black people had increased tenfold to about one thousand. Increasing moral doubts about slavery as well as the Revolution’s rhetoric of liberty contributed to gradual abolition, although unevenly across the region. Local free Black residents and migrants into the region formed communities around new African American churches in Philadelphia and whole new settlements, especially in southern New Jersey, including Timbuctoo in Burlington County, Free Haven (later renamed Lawnside) in Camden County, and Gouldtown in Cumberland County. A number of these free African settlements sat along New Jersey’s so-called “Greenwich Line” of the Underground Railroad. In Philadelphia, the number of African Americans continued to climb in the first part of the nineteenth century comprising more than 10 percent of the population by 1810 and climbing to 14,500 in 1830.

The settlement pattern in this agricultural economy centered on family farms operating as self-contained units and producing most of what families needed. Itinerant craftsmen traveled from farm to farm, selling wares that families could not produce for themselves. The Irish traveler Isaac Weld (1774–1856) reported in the 1790s that between Philadelphia and Lancaster he found “not any two dwellings standing together” except in Downingtown. Towns were simply not necessary to rural life. The network of thriving agricultural towns that William Penn had envisioned failed to materialize in most parts of the region. Some taverns standing at important crossroads offered travelers food, drink and beds, spawning small settlements around them. Even the county seats that sat within thirty miles of Philadelphia (the distance of one day’s ride with a loaded wagon) remained small despite their important functions like holding courts, recording deeds, and registering wills.

Riverside Industrial Outposts

Early industrial outposts sprang up along the rivers because early mills were powered by water wheels. Already by the American Revolution, the riverbanks of the region were dotted with paper mills, flour mills, textile mills, and ironworks. With advanced mechanization, the Delaware River spawned factory towns like Trenton and Bristol upriver from Philadelphia, along with Camden and Wilmington on the lower Delaware, along with the city of Chester, which by mid-nineteenth century grew into a diversified manufacturing center of ships, steel, iron, and brass. Other manufacturing centers grew on the banks of the Schuylkill, for example Conshohocken, which was spawned in the 1830s by iron foundries that manufactured sheet-iron, saws, shovels, and spades. Also along the Schuylkill River, a major manufacturing district rose in Manayunk, whose massive cotton and woolen mills led it to be labeled “the Manchester of America” in the 1830s.

In the Pine Barrens of southern New Jersey, sizable iron deposits spawned eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ironworks, while abundant sand enabled the production of glassware well into the twentieth century. Rather than functioning as rivals, those secondary industrial centers along the two rivers and in southern New Jersey tended to reinforce Philadelphia’s regional dominance because they shipped their products through the port of Philadelphia.

The largest of Philadelphia’s manufacturing satellites was Camden, which grew during the nineteenth century into a major industrial hub, particularly after the Civil War. By 1870 the city boasted factories that produced iron, nickel, oil cloth, and chemicals. By 1880, woolen mills also operated there, and at the turn of the twentieth century, Camden attracted the gigantic New York Shipbuilding Company, which expanded rapidly with the coming of World War I. The Victor Talking Machine Company also employed thousands of workers. Camden became the undisputed industrial center of South Jersey, although it never rivaled Philadelphia’s dominance in the region.

Philadelphia’s business and civic leaders cemented their preeminent position in 1854 when they successfully pressured the Pennsylvania legislature to adopt the Act of Consolidation merging more than two dozen towns clustered near the Philadelphia port. After two decades of social disorder and rioting in the 1830s and 1840s, civic leaders demanded more effective services and security, which they hoped could be provided by a large-scale professionalized government. The state legislature responded to their plea by consolidating twenty-nine separate districts, townships, and boroughs into a single large city, declaring that Philadelphia would henceforth function as both a county and city government.

Economic and Transportation Linkages

While county and township lines gained legitimacy as legal and political boundaries, they did not constrain economic activity. Settlers across the Delaware Valley established cross-boundary transportation links to help them succeed economically. Early in the colonial era, successful farmers began carting their surplus crops to Philadelphia to sell in the region’s central marketplace or to export by ship. The river separating Pennsylvania from New Jersey posed no great obstacle to New Jersey growers because as early as 1688 a commercial ferry crossed the river between Philadelphia and Camden.

William Penn had declared Pennsylvania county governments to be responsible for building and maintaining roads–a function that county officials often fulfilled simply by connecting short stretches of roadbed that had been built earlier by settlers. Such jerry-rigged roadways rarely provided the shortest route to Philadelphia, where most farmers wanted to cart their produce. The roadbeds were treacherous, clogged by tree stumps and other debris. To improve the situation, the legislatures of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware began chartering private investment groups to build and maintain toll roads, the first of which was the Lancaster Turnpike built between 1793 and 1795. Dozens of toll roads followed until the advent of railroads. Along with the turnpikes, early mill owners and craftsmen used the rivers to ship their surplus to other parts of the colonies through the Philadelphia port.

Nineteenth-century railroad builders seized opportunities to deploy the new rail technology not only to tie local industries to distant markets, but also to transport local residents quickly and conveniently around the region. Among the first railroads in the nation, the Camden and Amboy Railroad was chartered in 1830 to provide passenger and freight service between New York City and Philadelphia via Camden, where passengers would shuttle between train and ferryboat to cross the Delaware River. In 1831, the Delaware Railroad built a line from Philadelphia to Wilmington. It was intended primarily for passenger service but served as a secondary freight route. Then in 1832 the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad (PGN) began operating within Philadelphia County. Two great railroad companies–the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Railroad–gradually built and bought out other rail companies in the region to create networks of passenger service to virtually every community within thirty miles of Philadelphia and to recreational locations like the Jersey Shore.

Across the second half of the nineteenth century, railroad companies shaped development patterns that persisted for a century or more. Nineteenth-century homebuilders created suburban developments in Pennsylvania and New Jersey that relied on railroad transportation to carry office workers daily into and out of Philadelphia. Mostly these new developments sold housing to middle- and upper-income families. For example, in the late 1850s the Pennsylvania Railroad began serving the early residents of the Main Line communities built in the Pennsylvania suburbs of Montgomery and Chester Counties. Also in the 1850s, the Camden and Atlantic Railroad offered New Jersey suburban residents daily service between Philadelphia and suburbs like Haddon Township. The viability of such desirable suburbs depended upon the thirteen rail branches that ultimately were consolidated into Conrail in 1976.

The Highway Transportation Boom

The internal combustion engine brought massive change to the region, the most obvious sign of which was the highway network built from the 1950s onward, giving individual households and businesses convenient door-to-door access to virtually any location in the region. For the first time since its founding, Philadelphia was threatened by competition from surrounding communities. Both families and companies used their new freedom to move away from the region’s urban centers—not just Philadelphia, but also the region’s other industrial centers: Trenton, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington. After 1950 all those cities, including Philadelphia, suffered dramatic population losses which they never regained in the twentieth century.

Instead, population gains after 1950 concentrated in the region’s suburbs. The mid-distance suburbs attracted the most affluent households. Early in the history of suburban development, these communities proved to be appealing to well-to-do families who sought to escape the city yet wanted to remain within easy traveling distance of Philadelphia. Even at the turn of the twenty-first century, the majority of the region’s affluent households (that is, those whose annual household incomes exceeding $75,000) still tended to prefer locations far enough from the city to offer a suburban lifestyle, yet close enough to offer a reasonable commute to jobs, entertainment, and other downtown attractions. A smaller yet significant number of affluent residents gained access to those amenities by moving into row houses and condominiums within walking distance of downtown.

Many of the suburbs closest to the edge of the city developed as working-class communities with older housing stocks built at higher densities. The most challenged communities in the region tended to be older boroughs with affordable housing that attracted residents with modest incomes. Some older suburbs sat along the banks of the Delaware River, reflecting the early geographic influence of the main commercial waterway and the ongoing decline of manufacturing firms that lined it. Since these older communities tended to be completely built out, with little room for new investment, they experienced the greatest difficulty maintaining public services on a restricted property tax base.

Towns at the outer edge of the region proved to be attractive to middle-income households who wanted a suburban lifestyle but could not afford to buy homes in the pricey mid-distance suburbs. They were willing to trade longer commutes in order to gain suburban amenities. Springfield Township, for example, sits on the northern edge of Bucks County, bordering Northampton and Lehigh Counties. As late as the mid-1960s, over 90 percent of that township’s acreage was in agriculture, woods and water. Yet by the turn of the twenty-first century, the town’s population had exploded to five thousand people, prompting town voters to establish a tax to fund open space preservation by buying land and conservation easements. A New Jersey example was Southampton Township in Burlington County, originally settled by Quakers and slow to develop in the twentieth century. In the 1980s almost three quarters of its land was declared to be part of the Pinelands Preserve, off-limits to suburban development. The small village of Vincentown served as a town center for other parts of the township that came to be dotted with housing developments and retirement communities.

The Cities Assert Themselves

Leaders in the region’s urban centers responded to the threatening tide of post-World War II suburbanization by undertaking massive redevelopment projects to reassert the centrality of cities in the region’s growth. The largest of those urban renewal efforts in the 1960s occurred in Philadelphia with the redevelopment of Society Hill and the construction of the Penn Center office complex near City Hall. Then in the 1970s, planners launched a downtown project that would link the region’s two great railroads, the Reading and the Pennsylvania, into a single transit network. With funding that came largely from the federal government, SEPTA broke ground in 1978 on a massive underground project to connect the two downtown rail hubs. When completed in 1984, the Commuter Tunnel created a unified rail system anchored in downtown Philadelphia that spanned the Pennsylvania side of the region. It also provided access to Camden and the New Jersey suburbs by intersecting with the PATCO High Speed Line at the transit station at Eighth and Market Streets.

Other regional cities also responded to the suburban exodus with revitalization campaigns, many of them designed to accommodate automobiles, a priority regarded as vital to reviving downtowns. In 1957 Trenton unveiled plans to demolish a declining downtown district known as Coalport in order to replace it with a gleaming new industrial and residential complex. Trenton leaders also supported the state’s proposal to build the N.J. Route 29 highway through downtown Trenton along the banks of the Delaware River (a decision later criticized for separating the waterfront from the heart of the city). Also in 1957, Wilmington’s city council approved routing I-95 through several of the city’s stable neighborhoods and, in the 1960s, favored urban renewal projects that cleared an African American neighborhood to make way for what would eventually become government buildings. Camden’s pro-growth coalition, which styled itself the Greater Camden Movement, backed a 1962 renewal plan that based its optimistic vision on the assumption that the urban core could be revitalized by making central parcels of land available and assuring easy automobile access to jobs in the city.

As they pursued downtown revival, few urban planners in the 1960s foresaw that suburbanites would use highway networks not just to gain access to the city, but also to move easily from suburb-to-suburb, creating new patterns of commuting that bypassed central cities altogether. For example, the U.S. Route 202 corridor spanning Philadelphia’s northern suburbs became a particularly important path for suburb-to-suburb trips. Nor did planners foresee the rapid rise in the last decades of the twentieth century of reverse commuting from city residences to suburban jobs. In 1980, almost 15 percent of Philadelphia workers held jobs in the suburbs; by 2000 that percentage had climbed to almost 25 percent, and it continued increasing in the twenty-first century. Reverse commuters were virtually forced to use increasingly congested highways because the region’s rail system did not easily accommodate reverse commuting.

Some observers speculated that Philadelphia faced unusual difficulty defining its regional footprint because it competed for regional dominance against New York City to the north and Washington, D.C., to the south, the two powerful centers of the U.S. economy and government. Although long regarded as a drawback, this geographic midpoint appeared by the turn of the twenty-first century to confer advantages in attracting residents and businesses that sought a location in the Northeast Corridor but wanted to avoid the congestion and cost of New York and Washington.

Who Defines the Region?

Since 1950 the federal government’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has defined metropolitan regions for purposes of the U.S. Census. OMB’s original definition of the Philadelphia region in 1950 included the central city plus Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery Counties in Pennsylvania and Burlington, Camden and Gloucester Counties in New Jersey. OMB based that definition on the adjacent counties having a high degree of economic and social integration with the central city, measured by commuting and employment. Over the half-century that followed, the federal definition of the region changed multiple times, as the commuting shed of Philadelphia expanded to incorporate more suburban territory. By the 2010 census, the OMB had added three counties to its original definition: Salem County, New Jersey; New Castle County, Delaware; and Cecil County, Maryland.

Nongovernmental groups, however, have drawn the region’s boundaries in different ways depending on the specific goals they pursued. Across the twentieth century, a variety of quasi- and nongovernmental commissions, special-purpose authorities and nonprofit associations emerged to pursue particular projects and goals, each of them defining the region to fit its own objectives. Whereas voters expected county and township officials to act for the benefit of their own citizens, nongovernmental organizations had wider latitude to pursue regional goals. Starting in the twentieth century, the region benefited from the work of such nonelected bodies.

For example, the state legislatures of New Jersey and Pennsylvania established a joint commission to build the Delaware River Bridge, which opened to traffic in 1926 (and was subsequently renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge). That regional commission eventually became the Delaware River Port Authority, with responsibility for the operation and maintenance of three more bridges spanning the Delaware: the Walt Whitman, the Commodore Barry, and the Betsy Ross. It also took responsibility for the PATCO High Speedline carrying passengers between Philadelphia and multiple destinations in Camden County. Over time, DRPA expanded its definition of the Port District to include not only Philadelphia and its four suburban counties (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery) but also eight New Jersey counties (Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, Ocean and Salem).

“Greater Philadelphia”

In the mid-1960s the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission was established as a metropolitan planning agency to receive and expend federal transportation dollars. DVRPC defined the metropolitan area as including five Pennsylvania counties (Philadelphia, Bucks, Delaware, Chester, and Montgomery) and four New Jersey counties (Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Mercer) because these counties shared a transportation network of roads, rails, and airports. “Delaware Valley” was a term in vogue in the mid-twentieth century. But civic leaders in Philadelphia who were determined to emphasize the city’s primacy as the critical heart of a rapidly growing region favored the label “Greater Philadelphia.”

A good example was the regional chamber of commerce, which until mid-twentieth century had been known as the Trades League of Philadelphia. As an increasingly regional body, it changed its name to the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce in 1950. The chamber’s regional footprint duplicated the set of counties in the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission but added Salem County in New Jersey and New Castle County in Delaware.

Much of the responsibility for preserving the region’s natural environment has been carried by nonprofit organizations with the ability to work across formal boundaries that separate counties and municipalities. A leading example was the Natural Lands Trust, which began in 1953 as the Philadelphia Conservationists, a volunteer group of avid bird watchers who convinced Gulf Oil to deed 168 acres of prime bird habitat in the Tinicum marsh, property that became the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum. In 1961 the group institutionalized itself as the Natural Lands Trust, a nonprofit land conservation organization with a mission to protect remaining open lands throughout the region. They defined that regional scope broadly, operating in more than a dozen counties in Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey.

The Delaware River Keeper Network, established in 1988, also illustrated the ability of nonprofit organizations to work across governmental boundaries. That regionwide effort to protect the river enlisted volunteers to collect water samples from streams throughout the Delaware River watershed, testing for pollutants and advocating legislation to improve water quality. The Riverkeeper Network defined the region to include portions of all four states through which the river flows.

Promoting Tourism

Yet a different boundary line was drawn in 1996 with the creation of the region’s top tourism promoter, the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation, which became VisitPhilly.com in 2010. Its definition of “Philadelphia and the Countryside” included only the central city and the four suburban counties of eastern Pennsylvania. It omitted the New Jersey counties because the agency was heavily financed by the Pennsylvania state government.

Another long-established nongovernmental organization was the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia, founded in 1909 as the Municipal Research Bureau (MRB) with a mission to focus on cost-effective government services within the city. In 1954 the MRB merged with the Pennsylvania Economy League, becoming PEL’s Eastern Division. In addition to its central offices in Philadelphia, the Eastern Division of PEL operated county committees in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties, increasingly focusing attention on the region as a whole. For example, a 1963 Economy League study of regional transportation contributed to the creation of SEPTA. By 2007 the organization had formally re-named itself the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia to reflect its focus on the region, defined as southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware. As a nonprofit think tank, it analyzed regional problems and promoted policy solutions ranging all the way from high-quality early childhood education in southeastern Pennsylvania to the impact on the region’s economy of extending rail transportation from downtown Philadelphia to King of Prussia.

As is obvious from the examples above, no fixed definition of the region’s boundaries attained universal acceptance. Each organization pursued its objectives by constructing its own definition of the region. Lacking a standard definition of what constitutes “the region,” area inhabitants have rarely identified themselves as residents of Greater Philadelphia, with the possible exception of sports fans throughout the city and suburbs who have historically identified with the city’s major teams.

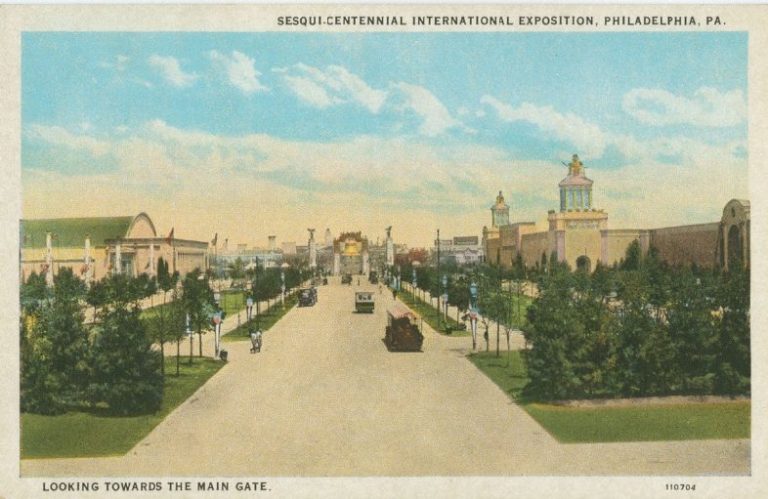

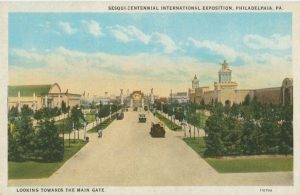

Philadelphia became one of only a handful of cities that built as many as three stadiums within a single sports complex. The chosen site in south Philadelphia had been developed in the 1920s to house Sesquicentennial Stadium for the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition. In 1967 the Flyers hockey team and the 76ers basketball team moved into the Spectrum Arena in that area. Then in 1971 nearby Veteran Stadium became home to the Phillies baseball team and Eagles football team. Both facilities served their resident teams until the opening decade of the twenty-first century, when new facilities replaced the older venues. Although other locations were considered, the teams chose to remain in the sports complex in South Philadelphia where they could be easily reached from the suburbs by car because of the location near exits off both I-95 and I-76. The fact that thousands of avid sports fans from the suburbs poured into South Philadelphia for every home game fostered their identification with the rest of the region as perhaps no other activity could.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and Associate Editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University