Kwanzaa

Essay

Because of its large African American population and the presence and influence of prominent Black Nationalist individuals and organizations, the Philadelphia area has been especially active in celebrating Kwanzaa, an African cultural holiday that emerged out of the Black Nationalist Movement of the 1960s. Kwanzaa emphasizes remembering and reconstructing African identity, which was forcibly erased in the United States by enslavement of African peoples.

Created by California State University Professor Maulana Karenga (b. 1941) in 1966, Kwanzaa is a nonreligious holiday that originates from the Swahili phrase “matunda ya kwanzaa,” meaning “first fruits of the harvest.” The holiday is fashioned to represent the various harvest festivals that take place in many African communities and is rooted in a tradition that extends back to ancient Egyptian civilization. Kwanzaa is celebrated from December 26 to January 1 with each day focusing on one of seven principles that make up the Nguzo Saba—Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity), and Imani (faith). While no official statistics exist, Karenga has estimated that Kwanzaa is celebrated by up to twenty-eight million people around the world.

Celebration of Kwanzaa in Philadelphia began as early as 1968, when Falaka Fattah (b. 1931) and her husband, David Fattah (b.1943), cofounded a group home for troubled African American males called the House of Umoja. This grassroots project, named after the first principle of Kwanzaa, incorporated all seven principles in daily operations as a methodology for ending gang wars in Philadelphia. The House also held an annual Kwanzaa celebration in conjunction with its anniversary. In 1969, the Urban Survival Training Institute organized one of the first large community Kwanzaa celebrations in Philadelphia. During the 1970s several cooperative groups–including the Camden Kwanzaa Committee, the Kwanzaa Planning Committee, and the Kwanzaa Cooperative–formed to organize Kwanzaa celebrations in the greater Philadelphia region.

Reginald Mtumishi (1945-2009), cofounder and chairman of the Kwanzaa Cooperative, was also an early celebrant of Kwanzaa who influenced its proliferation in Philadelphia. A student and friend of Maulana Karenga, Mtumishi brought the Kwanzaa creator to Philadelphia each year to be the keynote speaker for one of the many events he organized during the week of Kwanzaa. Additionally, Mtumishi introduced the holiday to the Philadelphia Department of Human Services and organized celebrations at the Free Library of Philadelphia each year, contributing greatly to the local growth and acceptance of the holiday.

Philadelphia area residents have been influential in promoting the principles and celebration of Kwanzaa both locally and internationally. In 1980 Baba Abiodun (also known as Phillip Harris, b. 1937) produced the award-winning film Kwanzaa: The Gathering of a People, one of the first major documentaries on Kwanzaa. Baba Abiodun also served as chair of the Kwanzaa Planning Committee from 1971-74 and performed as a griot (storyteller) at many Kwanzaa and African cultural events with the nationally acclaimed Universal African Dance and Drum Ensemble, founded at the Unity Community Center in Camden, New Jersey, by Robert Dickerson (b. 1954) and his wife, Wanda. (b. 1957). For years, the Dickersons and their ensemble participated in Reginald Mtumishi’s Kwanzaa celebrations in Philadelphia. Following Mtumishi’s death in 2009, the Dickersons took over hosting the yearly celebration that featured the ensemble and Maulana Karenga.

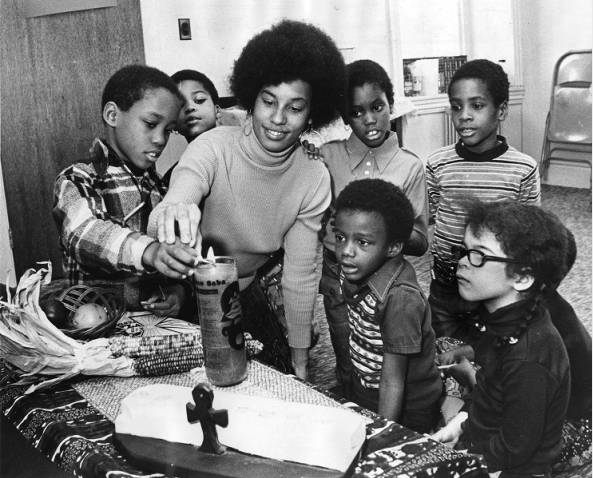

While many people celebrate Kwanzaa at home with family, communal celebrating also has been emphasized. Each December, pre-Kwanzaa activities held by civic, community, religious, and education organizations have included workshops, forums, bazaars, and instructional candle lighting ceremonies to educate the community about how to celebrate Kwanzaa, provide opportunities to purchase Kwanzaa-related items, and spread information about Kwanzaa events. Celebrations have included dance drum exhibits and workshops, arts and crafts, candle-lighting ceremonies, art exhibits, storytelling, and spoken word and poetry readings.

Beginning in 1986, the African American Studies Department at Temple University hosted an annual Kwanzaa celebration for its students and the Philadelphia community. Molefi Kete Asante (b. 1942), chair of the department and founder of the first doctoral program in the field of Black Studies, also began an annual Kwanzaa celebration at the MKA Institute (an African think tank and nonprofit public policy organization) in conjunction with the Philadelphia chapter of Afrocentricity International. Asante’s son, M.K. Asante (b. 1982), directed the award-winning Kwanzaa documentary The Black Candle, narrated by Maya Angelou (1928-2014).

In 2013, Oshunbumi Fernandez (b. 1974), lead organizer of Philadelphia’s annual Odunde festival, collaborated with celebrated music producer Kenny Gamble (b. 1943) to start Kwanzaabration—a community event that aimed to educate children and adults about Kwanzaa and to foster a yearlong celebration of the principles of Kwanzaa. The project carried on the goals of Kwanzaa’s founders to demonstrate and defend the cultural unity of Africans both on the continent and throughout the diaspora.

Christina Afia Harris is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Africology and African American Studies at Temple University. This essay is derived from her research and her personal experience celebrating Kwanzaa. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Molefi Kete Asante Institute in Germantown (WHYY, May 8, 2012)

- African think-tank opens in Germantown to 'be a part of a cultural renaissance' (WHYY, May 23, 2012)

- 3 places to celebrate Kwanzaa this season (WHYY, December 26, 2013)

- Kwanzaa celebrates 50 years of honoring African-American culture (WHYY, December 26, 2016)