Women’s Clubs

Essay

The woman’s club movement began throughout the United States in the late nineteenth century. Although initially focused on self-improvement, women’s clubs in the Philadelphia region as in the nation quickly extended their goals to include community activism. Drawing upon contemporary assumptions about the inherent differences between men and women, leaders of the club movement argued that women’s spiritual and moral superiority prepared them for a more significant role in reforming society. Moreover, club members often utilized the rhetoric of domesticity to support women’s involvement, claiming their work would be an extension of their domestic role within the household.

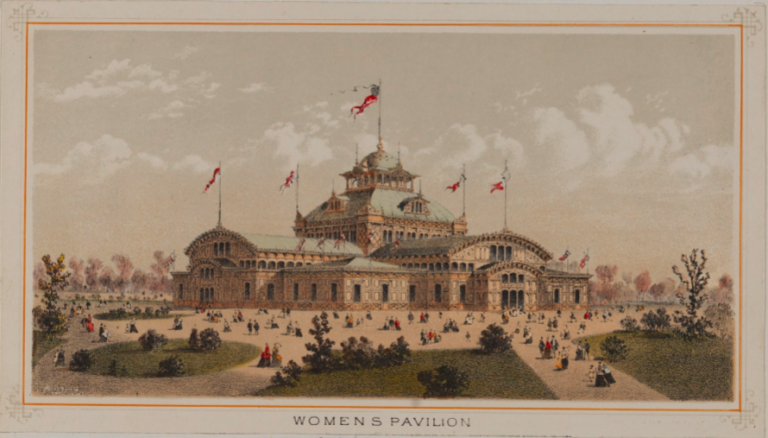

Building on the tradition of charitable work of early nineteenth-century church and benevolence societies, women’s clubs maintained a focus on social welfare, anticipating much of the work later taken up by the Progressive movement of the 1890s. The generation of women who established these clubs often built on the infrastructure established by women in the antebellum era. The nation’s first women’s club, the Sorosis Club of New York, formed in 1868, but in the Philadelphia area, women’s clubs emerged in the aftermath of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition. Eliza Sproat Turner (1826-1903) and Elizabeth Duane Gillespie (1821-1901), president of the Women’s Committee for the Centennial, joined other local women in hosting tea parties to raise money to build the Women’s Pavilion in West Fairmount Park. The Women’s Pavilion highlighted the significance of women’s contributions to society, including their support for the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. In the Pavilion’s newspaper, Turner published a rationale for the formation of women’s clubs, which in turn influenced the development of the women’s club movement throughout the nation. The impact of the Pavilion extended beyond national borders as women continued to reframe the historical narrative to include themselves as full participants whose contributions were not limited to the home.

Building on the energy unleashed with the Women’s Pavilion, Turner joined Sarah Catherine Fraley Hallowell (1833-1914) in 1877 to establish the New Century Club, one of the first women’s clubs in the nation. Initially conceived to promote science, literature, and art, by the turn of the twentieth century the club extended its influence to include social reform, offering programs to address municipal concerns as well as other issues related to women and children.

The New Century Guild emerged as a committee of the New Century Club, and in 1882 became an independent organization where Turner sought to expand educational and political activities related to women and their participation in the workforce. In 1893, the Guild became a committee of the newly formed New Century Trust. With the support of financial gifts, the Guild secured ownership of its own property, a house at 1307 Locust Street, which allowed it to offer more vocational training, as well as self-improvement programs. Turner also held one of the first local meetings in support of women’s suffrage meetings at the Guild’s building.

Federations of Women’s Clubs

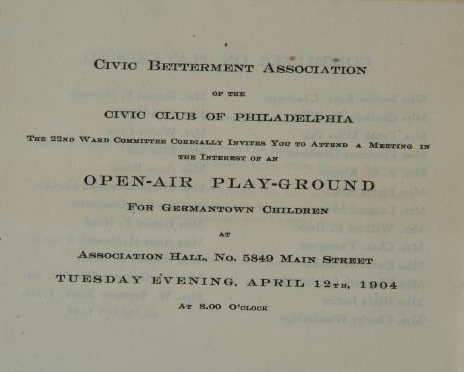

Women from the New Century Club also helped to organize the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) in 1890 under the leadership of Jane Cunningham Croly (1829-1901), who is credited with founding the Sorosis Club of New York. Organizations spread throughout the Philadelphia region. A New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs formed in 1894; the Woman’s Club of Camden not only led to the founding of Camden’s library system but also increased early childhood education and public playgrounds. In Delaware, where the New Century Club of Wilmington formed in 1889, a State Federation of Women’s Clubs began in 1898.

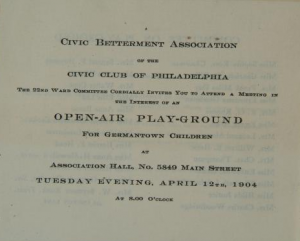

While the New Century Club remained the most prominent club in Philadelphia, the role and impact of local women’s clubs increased with the establishment of the Acorn Club in 1889 and the Civic Club of Philadelphia in 1894. Excluded from formal participation in electoral contests, women maintained political influence through voluntary organizations, often working in cooperation with men interested in municipal reform. In order to facilitate a greater coalition with men, Civic Club leaders such as Sara Yorke Stevenson (1847-1921) carefully defined their goal as work on behalf of women and children. Members of the Civic Club, organized into four departments for municipal government, education, social service, and art, conducted research and disseminated reports on issues ranging from education to housing. Leadership from the Civic Club and the New Century Guild supported each other by sending letters, delegations, as well as fund-raising to lobby for a wide variety of municipal and statewide reform initiatives, including the environment and conservation. Their investigations often led to legislation, including the Philadelphia Public School Reorganization Act of 1905, which granted authority to the schools superintendent to reform and standardize the city’s public schools, and the Philadelphia Housing Code of 1913, which established a Division of Housing and Sanitation in the Department of Health and Charities to improve standards for home lighting, ventilation, and occupancy.

The membership of most women’s clubs consisted primarily of white, middle class women. In response, African American women began organizing and by 1896 the National Association of Colored Women united more than one hundred local clubs under the leadership of Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954). Founded in 1870, the Colored Women’s Christian Association established what many consider to be the oldest African American YWCA. (Young Women’s Christian Association) in Philadelphia. The Southwest Branch, later known as the Southwest-Belmont Branch of the YWCA, maintained a significant presence in the Philadelphia African American community. Like women’s clubs, the Southwest Branch provided educational and social opportunities. With the financial support of John Wanamaker (1838-1922), the branch operated the Elizabeth Frye House to help African American women find affordable housing. Drawing primarily on the efforts of women from the Pittsburgh area, such as Rebecca Aldridge (1851-1933), the Pennsylvania State Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs was established in 1903. These organizations participated in anti-lynching campaigns and addressed educational and social reform issues.

The state federations of women’s clubs in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware contributed to the growth of the GFWC as the nation’s largest women’s voluntary association. The advocacy of Alice Leakey, club member from Cranford, New Jersey, ultimately led to the passage of the federal Pure Food and Drug Act (1906). Other notable efforts supported by women’s clubs include seatbelt legislation and the expansion of public libraries. Although the Civic Club of Philadelphia formally distributed its assets to other civic organizations in 1959, in the early decades of the twenty-first century the Acorn Club, formed primarily to promote “literary, musical and artistic tastes,” maintained a private membership. In 2012, at its original headquarters site at 1307 Locust Street in Philadelphia, the New Century Trust celebrated nearly 120 years of work improving the educational, economic and social status of women and girls.

Women’s clubs continued to increase, with more than eighty thousand members affiliated with the GFWC in the early twenty-first century. The mission statement, which remained centered on a commitment to education and civic involvement, broadened its scope to include supporting the arts, preserving natural resources, promoting healthy lifestyles, and working toward world peace and understanding. To that end, the State Federation of Women’s Clubs in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey continued to support higher education through annual scholarships and grants. With more than fifty clubs in the early decades of the twenty-first century, the Greater Philadelphia region maintained a strong affiliation with the GFWC and presence in the nationwide activism of women’s clubs.

Catherine Murray is a Ph.D. candidate in History at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- GFWC Women's Club of Newtown Square

- Acorn Club

- New Century Trust

- Minerva Parker Nichols: Architect of Gender Equality (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Viva Minerva! Celebrating America’s First Independent Female Architect (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Still Advancing The Goals Of The “New Century” (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- History of the Women's Club of Camden, New Jersey, 1894-1919 (dvrbs.com)

- The Porch Club of Riverton, New Jersey

- General Federation of Women's Clubs