Mexicans and Mexico

By Domenic Vitiello, Hilary Parsons Dick, Danielle DiVerde, and Veronica Willig

Essay

Greater Philadelphia’s economic ties to Mexico date to the era of European colonization. However, substantial Mexican immigration to the region started only in the 1970s, in Chester County’s mushroom growing towns, and in the 1990s in Philadelphia. Still, Mexicans became the region’s second-largest immigrant group in the early twenty-first century and were the largest immigrant group in the United States as well. With this surge in population, Mexicans had a substantial impact on the region’s culture and economy, sustaining its agricultural sector and revitalizing once-depressed city and suburban neighborhoods.

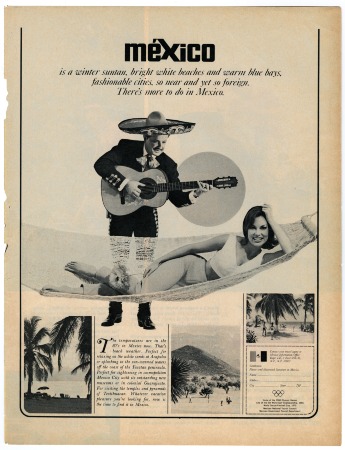

Greater Philadelphia’s ties to Mexico were relatively modest before the late twentieth century. Philadelphia merchants in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did a small trade with Mexican ports, mainly Alvarado and Veracruz. Typically, the Philadelphia ships brought re-exports from Europe and Africa, including cocoa, textiles, jewelry, and wine, and returned with specie, gold bullion, and cochineal for use in dyes. Some Philadelphians, including members of the First City Troop cavalry, fought in the Mexican-American War in 1845-46, in which the United States took the territories between Texas and California. In the twentieth century, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology acquired some ancient artifacts from Mexico, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired paintings, sculptures, and prints by prominent Mexican artists. As the tourism industry expanded in Mexico across the twentieth century, residents of Greater Philadelphia also increasingly visited the country, especially resorts like Acapulco and Cancún.

Small numbers of Mexicans also settled in the Philadelphia region in the twentieth century. In the 1910s and 1920s, as Mexicans increasingly emigrated in search of employment, some came to work in agriculture, construction, and railroads, and a few stayed in the area. During World War II, labor agents recruited Mexican men to work mainly for railroads in the region, part of a national effort to address wartime labor shortages, and again a small number remained. In the 1970s, another small group of Mexican men and women settled in Philadelphia. Some started small businesses in North Philadelphia, including Razo’s Grocery and La Raza restaurant at Second and Allegheny, and established Mexican teams in the Hispanic Soccer League of Philadelphia that played in Hunting Park. Mexican men also worked seasonally in the region, especially the agricultural townships of southern New Jersey, picking blueberries in Hammonton or tomatoes in Vineland and Bridgeton. These became more permanent settlements of Mexican families in the late twentieth century.

Greater Philadelphia became a significant destination for Mexican immigrants in the 1990s, when Mexican migration to the U.S. accelerated and spread beyond the older gateway regions of New York, Chicago, and the Southwest. Most migrants came from working-class or rural backgrounds in Mexico, often places whose agricultural economies struggled after the enactment of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. Many also came from the New York metropolitan region, attracted by Greater Philadelphia’s lower costs of living and seeking greater safety and opportunities for their children. By the early twenty-first century, Mexicans had become the second-largest immigrant group in the city of Philadelphia and the broader region, even though Mexicans are commonly undercounted in U.S. Census estimates.

Agricultural Towns

The first large concentration of Mexican immigrants in Greater Philadelphia grew up in the mushroom farming capital of the world in southwestern Chester County, around Kennett Square, Avondale, Oxford, and Toughkenamon. Like South Jersey agriculture, this area drew migrant labor beginning in the early twentieth century, first Italians, then African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and finally Mexicans. Mexican migration to this area began in the early 1970s, when some migrants already working in Chicago learned of the mushroom work from Puerto Ricans who had relocated from the region.

Most Mexican migrants in southern Chester County came from the state of Guanajuato, and many gained legal status in the United States through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. By the early twenty-first century, the population of people of Mexican origin in southern Chester County was around forty thousand. In Kennett Square, in 2014 at least half of the town’s six thousand residents were of Mexican origin.

Starting in the 1980s, Mexican men working in Vineland and Bridgeton also brought their wives and children to live in New Jersey. Some of these families opened small businesses like grocery stores and restaurants. Mexicans succeeded Italians and Southeast Asians as the primary resident agricultural labor force in South Jersey. Many Mexicans also passed through the region in the seasonal migration of farmworkers harvesting fields up and down the East Coast.

Suburbs

Beginning in the 1990s, significant numbers of Mexicans settled in suburban towns in the region, with the largest population in Norristown, the county seat of Montgomery County. The origin story relates that a man of Italian descent visited Acapulco on vacation, met and fell in love with a Mexican woman there, brought her back to Norristown, and she in turn invited family and friends. This began a “chain migration” in which Mexicans from Acapulco, Puebla, and Mexico City came to settle or work seasonally in the town’s construction and landscaping businesses. By 2000, the Census counted three thousand people of Hispanic origin in Norristown, and almost ten thousand by 2010, most of whom were Mexican immigrants and their children, though a smaller Puerto Rican community also contributed to those figures. Mexicans revived the commercial district of West Marshall Street and surrounding blocks and helped regrow the population of this older industrial town that lost residents in the 1970s and 1980s.

Mexican immigrants settled in suburban towns across the Philadelphia region in the first part of the twenty-first century. In Norristown, Pottstown, Hatboro, Bristol, Upper Darby, Pennsauken, Swedesboro, and other working-class suburbs, Mexicans settled usually in small numbers, finding affordable rents in towns that scholars Michael Katz and Kenneth Ginsburg have called “reservations for low-wage labor.” They commonly found work in landscaping, housekeeping, construction, and other services for the more affluent residents of nearby suburbs, as well as their malls and office parks.

Philadelphia and Camden

While Puerto Ricans remained the largest Latino group in the cities of Philadelphia and Camden, the Mexican communities of both cities grew significantly since the late 1990s. Migrants from the state of Puebla came to dominate the Mexican populations of Philadelphia and Camden, arriving first from New York and subsequently attracting newcomers directly from Mexico. People from the rural town of San Lucas in the mountains of Puebla settled in East Camden, via New York. One man from San Lucas invited an acquaintance from the neighboring town of San Mateo Ozolco in Puebla, who ventured across the Benjamin Franklin Bridge one day and found a job at the upscale Mexican restaurant Tequilas in Center City Philadelphia. He settled in South Philadelphia, and by the early 2000s roughly half of the residents of San Mateo had made their way to Philadelphia, along with other Mexicans from Oaxaca, Mexico City, and other states. Between 2000 and 2010, the Mexican population of Philadelphia more than doubled from 6,000 to 15,500, according to the Census.

Mexican immigrants played a large role in the revitalization of Philadelphia and its neighborhoods in the early twenty-first century, including the city’s restaurant and construction booms and gentrification of neighborhoods surrounding Center City. Mexicans opened shuttered storefronts in the historic Italian Market, which the city government had labeled blighted at the turn of the century, and established a vibrant Mexican restaurant scene in this and other neighborhoods. South Philadelphia became home to the second-largest community of Mexicans in the region, after the area around Kennett Square. As in the suburbs and agricultural towns of the region, and in the nation at large, what was initially a community composed mainly of single men transitioned to a community of families, a shift reflected in the opening of dress shops, bakeries, and other family-serving shops in the Ninth Street Market. Like the region at large, by the 2010s an estimated more than twenty thousand Mexican immigrants lived in neighborhoods across the city, contributing substantially to the reversal of Philadelphia’s decades of population decline.

Mexican Civil Society

As Mexican communities grew in Greater Philadelphia, organizations that served their needs—social service organizations, Catholic missions, migrant-led hometown associations, and immigrant rights groups—began to emerge, providing a range of services, from English as a Second Language classes to legal aid in Spanish. Some adapted from initially serving Puerto Rican constituencies, like the health and educational programs of La Comunidad Hispana in Chester County and Acción Comunal Latinomericana de Montgomery County (ACLAMO) Family Centers in Norristown and Pottstown. Others grew out of the Catholic Church, like Mission Santa Maria in Chester County and the Church of St. Patrick in Norristown, which offered bilingual services and hosted events for Mexican Independence Day and the feast day of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. CATA–the Farmworkers Support Committee–established by Puerto Ricans in South Jersey in 1979, advocated for Mexicans in the Bridgeton and Kennett Square areas. The Philadelphia Area Project on Occupational Safety and Health and the newer Restaurant Opportunities Center supported Mexicans working in the construction, landscaping, and food industries. Legal aid organizations assisted people without U.S. legal status who were brought to the region as children in applying for legal employment status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program of President Barack Obama (b. 1961).

In South Philadelphia, JUNTOS emerged as a community organizing and immigrant rights group supporting day laborers, immigrant parents advocating in public schools, and hometown associations. The hometown association from the village of Oyometepec in Puebla raised funds and organized community members in Mexico to plant trees for reforestation. Grupo Ozolco raised funds to build a high school and repair the main church in San Mateo, and with JUNTOS it established a bi-national cooperative in which members in Mexico grow and process indigenous blue corn and members in Philadelphia sell a corn flour called pinole to restaurants, cafes, and bakeries. JUNTOS members also helped found the Puentes de Salud health clinic, its community-led health promotion corps, and the Casa Monarca cultural center. Other cultural organizations in South Philadelphia included the San Mateo Carnavalero, which organized traditional festivals and participated in the Mummers Parade, as well as Philatinos Radio and other media ventures aimed at the Mexican community. The Mexican government opened a consulate on Independence Mall, where it established the Mexican Cultural Center as well.

Politics and Immigrant Rights

While many Philadelphians recognized Mexican migrants’ social and economic contributions to the region, the fact that most Mexican immigrants were in the United States illegally made their migration controversial. The United States recruited labor from Mexico for over a century, while never providing sufficient visas for this labor force to come legally. One controversy occurred in South Philadelphia, where Joey Vento (1939-2011), the owner of Geno’s Steaks, drew attention in early 2006 over a sign he placed in his establishment: This is AMERICA. WHEN ORDERING PLEASE “SPEAK ENGLISH” (emphasis in the original). Vento became a national figure in the illegal immigration restriction movement that erupted that year, demanding that his Mexican neighbors assimilate more quickly. That same spring, Philadelphia became the first city in the nation to mount immigrant rights protests, led by JUNTOS, in response to the U.S. House of Representatives passage of a bill aimed at criminalizing unauthorized immigrants and their supporters. Later that summer, first Hazleton in the Poconos and then the Philadelphia suburbs of Bridgeport, Pennsylvania, and Riverside, New Jersey, passed “illegal immigration relief acts” seeking to punish landlords and employers of unauthorized immigrants. Riverside soon repealed its ordinance, and federal courts later struck down these laws.

By contrast, local governments in Philadelphia and Norristown sought to welcome and protect immigrants in the U.S. illegally. In 2003, Norristown passed an ordinance recognizing the Mexican consular ID card as valid documentation for accessing local services such as public schools, libraries, and health clinics. Town council members convinced local banks to do the same for Mexicans to open bank accounts locally. In the early 2000s, the administration of Mayor John Street (b. 1943) issued a directive reminding Philadelphia police that they may not ask people about their immigration status, a policy originally established in the 1980s to protect Central American asylum seekers. In the late 2000s and 2010s, the city’s mayors and city council repeatedly reaffirmed Philadelphia’s Sanctuary City status, refusing to cooperate with increasing federal detention and deportation efforts under Presidents George W. Bush (b. 1946) and Obama. The only hiatus in this Sanctuary City policy came when Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) repealed it at the very end of his term, though incoming Mayor James Kenney (b. 1958) reinstated it on his first day in office. The New Sanctuary Movement, a coalition of city and suburban congregations supported by JUNTOS, was largely responsible for inspiring and sustaining this commitment.

As Philadelphia’s connections to Mexico grew markedly during the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, Mexican immigrants, many of whom were undocumented, contributed mightily to the city and region’s cultural and economic vitality. Although immigrant arrivals from Mexico declined after the recession of 2008, their number continued to grow and those already in Greater Philadelphia deepened their ties to local communities as they raised new generations of Mexican Philadelphians.

Domenic Vitiello is Associate Professor of City Planning and Urban Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. He is former board chair of JUNTOS and is co-editor with Thomas J. Sugrue of Immigration and Metropolitan Revitalization in the United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

Hilary Parsons Dick is an Associate Professor of International Studies at Arcadia University. She completed her Ph.D. in Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2016, she was a Wenner-Gren Hunt Fellow, during which time she completed her first book, Words of Passage: Discourse, National Belonging, and the Imagined Lives of Mexican Migrants (forthcoming, spring 2018, The University of Texas Press).

Danielle DiVerde has a B.A. in International Studies and Spanish from Arcadia University. She has worked as research assistant to Hilary Parsons Dick for three years and is currently a Lead Customer Service Representative and Latin America Specialist at MEJDI Tours.

Veronica Willig has a B.A. in International Studies from Arcadia University. She has worked as Hilary Parson Dick’s research assistant for two years and is currently serving as an AmeriCorps Community Projects Coordinator with YouthBuild Philadelphia Charter School.

(Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Play written for Philly butcher shop a lesson in Mexican-American history (WHYY, February 24, 2016)

- Philadelphia council president at odds with the mayor over sanctuary city status (WHYY, February 2, 2017)

- Some Pa. cities helping communities when immigration raids happen (WHYY, February 16, 2017)

- Rain, fear can't dampen Cinco de Mayo in Kennett Square (WHYY, May 8, 2017)

Links

- ACLAMO Family Centers, Norristown

- CATA – Farmworkers Support Committee

- JUNTOS

- Potehtli-Pinole Project (YouTube)

- Puentes de Salud

- The Mexican Cultural Center

- Church of St. Patrick

- "Mexican Community Comes of Age in South Philadelphia"

- Mexican Labor and World War II: The Bracero Program Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)