Colonization Movement (Africa)

Essay

The African colonization movement, dedicated to resettling North American free Black people in West Africa, caused heated debates in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century. Proposals to remove free Black individuals from North America date from the 1770s, but the heyday of African colonization occurred between 1818 and 1865. Often described as a “return to Africa,” the resettlement plans actually focused on free Black people who had never set foot on African soil. Colonization is better described as a semivoluntary expatriation than as a return to a homeland.

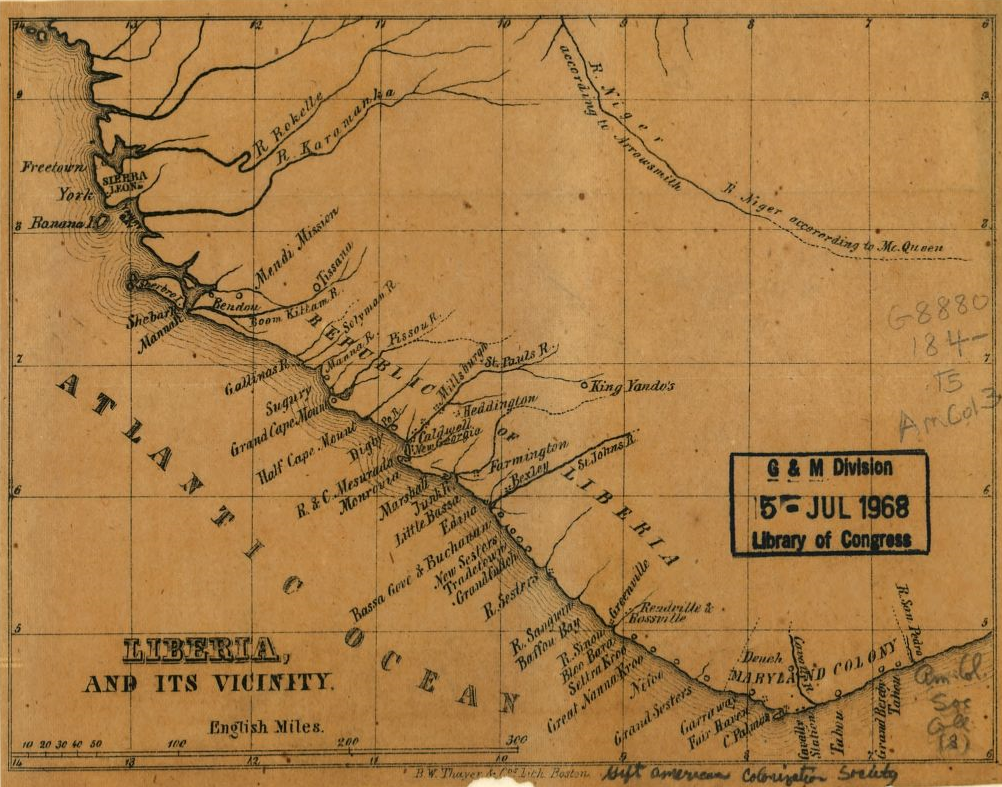

White Americans were the most active in promoting colonization, but many Black people desired opportunities outside North America in places that appeared to offer greater self-determination and economic gain. The first colonizationists, Black and white, envisioned various territories for expatriates. The West Indies, which after 1776 seemed separate from the mainland to most citizens of the United States, were a possibility. Haiti was the most commonly mentioned island. In West Africa, Sierra Leone, a British colony (first proprietary, then Crown), also seemed a possibility, since its residents included Black settlers from England, North America, and Jamaica. By the early 1820s, American colonizationists focused on Cape Mesurado in Africa, where Monrovia (named for President James Monroe) was established in a territory soon called Liberia (after the Latin word for freedom). Some also proposed removing free Black people to the American western frontier, where they might be distant from white Americans as well as useful as a buffer against Native Americans.

Although often considered an American colony, Liberia was a territory initially purchased by American settlers from African chiefs in several transactions in the 1820s with financial support from the American Colonization Society, a national organization founded in Washington, D.C., in 1817. The Americo-Liberian settlement expanded from the coastal town of Monrovia along the banks of the St. Paul and Mesurado Rivers. Settlers declared Liberia an independent nation, with its own constitution, in 1847. It was then home to about 3,000 Americo-Liberians, a number sufficient to establish political dominance over native Africans but far fewer than the number of free Black individuals that colonizationists had hoped to resettle from the United States.

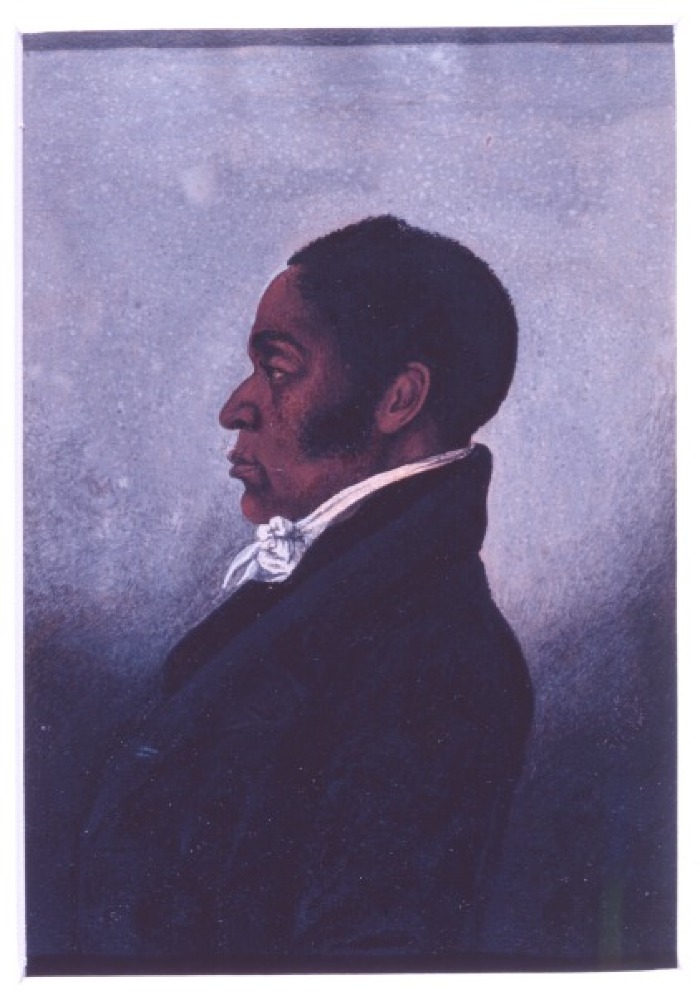

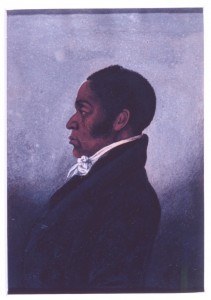

In Philadelphia, members of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society discussed colonization in the 1810s as a response to the growing number of freedpeople or runaways coming to Philadelphia from Southern states. At that time, leaders of Black Philadelphia including Richard Allen (1760–1831) and James Forten (1766–1842) endorsed colonization. But soon, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, colonizationist sentiment was attacked from several angles. In 1817 a gathering of Black Philadelphians at Mother Bethel Church denounced colonization as an insult to African Americans and a forced removal hidden behind a thin veil of voluntary emigration.

Reversal of Views

Allen and Forten modified their earlier views although at times they articulated lukewarm support for colonization. Allen declared: “This land which we have watered with our tears and our blood, is now our mother country, and we are well satisfied to stay where wisdom abounds and the gospel is free.” Similarly, in an 1818 address to white Pennsylvanians, Forten stated the desires of free Black persons to remain in their homes and to assist in the abolition of slavery and the improvement of Black life in the United States. In 1818, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society moved firmly against colonization by noting that most free Black people were committed to remaining in the country of their birth, that progress for free African Americans was most likely to occur in the United States, and that Sierra Leone had failed to thrive, after two decades, as a home for Black emigrants from Canada and England. Still, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society expressed belief that resettlement might be salutary in some circumstances.

Despite these mixed opinions, the American Colonization Society enjoyed strong support in the Greater Philadelphia region. Robert Finley (1772–1817), who led the committee that established the American Colonization Society, was born in Princeton, New Jersey. Like most states beginning in the 1820s, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland had local colonization societies that identified likely settlers and drummed up financial support for travel and the needs of the Liberian settlements. Often these societies raised funds for the national organization as well. A settlement at Cape Palmas was known as “Maryland in Africa,” then the Republic of Maryland, until it was annexed by Liberia in 1857. Baltimore was a common point of embarkation for emigration to Liberia. Delaware politicians joined with their counterparts in Southern states in the call for colonization.

Even after the Pennsylvania Abolition Society condemned African colonization in 1818, Philadelphians were involved in the movement of free Black people to Liberia. Episcopal Bishop William White (1748-1836) became a vice president of the American Colonization Society in 1819. Philadelphia Quaker Roberts Vaux (1786-1836) became a colonizationist in the 1820s, when he decided that a Liberian settlement would help suppress the African slave trade as well as provide a home for victims of the slave trade (known as recaptives) who were seized by the American government, sometimes at sea, from illicit slave-traders. Other Quakers including Joseph Hemphill (1770-1842) and Sarah Moore Grimké (1792-1873) adopted the colonizationist cause. Philadelphia luminaries such as Mathew Carey (1760-1839) and Elliott Cresson (1796-1854) also supported colonization.

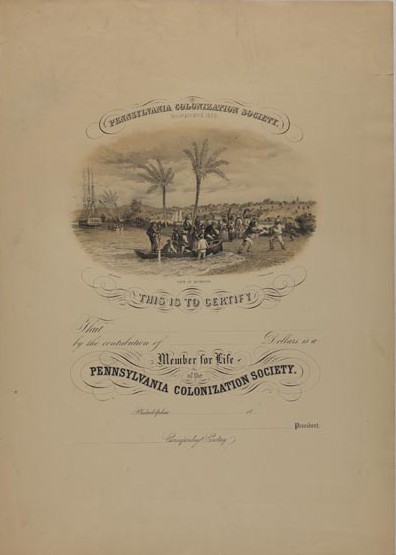

Colonization Societies Emerge

The Pennsylvania Colonization Society formed in 1828 to promote Black emigration from Pennsylvania as well as to fund transportation of freedpeople from other states to Liberia. It was followed in 1834 by the Young Men’s Colonization Society of Pennsylvania, which, in cooperation with the national society and the Colonization Society of the City of New-York funded the travel of 126 freed Afro-Virginians from Norfolk to a new settlement in Liberia called Bassa Cove. In 1835 this settlement was attacked by the dominant local slave trader, King Joe. Although the new settlers were routed in the first battle, they were able, with the assistance of the Monrovian settlers, to force King Joe to cede territory to the United Colonization Societies of New-York and Pennsylvania. However, the Young Men’s Colonization Society of Pennsylvania could not maintain itself as a separate organization and was absorbed into the American Colonization Society in 1838.

A Philadelphia Ladies’ Liberia School Association formed in 1832 under the leadership of Quaker Beulah Biddle Sansom (1768-1837). The Young Men’s Colonization Society of Pennsylvania had been calling for women to support the work of colonization, and in the early 1830s Philadelphia women began raising money to support schools in Liberia. Such charitable support was part of a larger pattern of women’s benevolence in antebellum America. Missions and schools were considered natural interests of middle-class Christian women. The enthusiasm of the Ladies’ Liberia School Association remained high throughout the 1830s, as its members funded construction of schoolhouses and selected teachers for its schools in Liberia. This enthusiasm declined in the 1840s as the funds raised by the association proved inadequate to maintain the Liberian schools and as the growth of the American Anti-Slavery Society (always opposed to colonization) dimmed the association’s Liberian hopes. Indeed, one of the association’s teachers, Massachusetts-born Ishmael Locke, left Liberia in despair over the state of the schools and ultimately settled in Philadelphia, where he became principal of the Institute for Colored Youth in the 1850s. His grandson, born in Philadelphia, was Alain Leroy Locke (1885-1954), proponent of the arts and thought of the Harlem Renaissance.

Some of the early Americo-Liberian settlers were Black Philadelphians. By 1822, about fifty-four Black Philadelphians had emigrated to Liberia (a tiny number compared to about 10,000 free Black individuals in Philadelphia, but significant in the settlement). One of the folk heroes of early Liberia was Matilda Newport, a young woman who emigrated from Philadelphia in 1820 around age twenty-five and, according to the legend, stood her ground singlehandedly with a rifle in a battle with local people in 1822.

Both Black and white residents of the Philadelphia region thus participated in a resettlement effort that would have momentous implications in the modern world. Although colonization’s advocates and its foes expressed mixed sentiments about the resettlement, and Philadelphians’ initiatives were mostly limited to the 1820s and 1830s, the repercussions of colonization both in the United States and in West Africa made it a crucial phase in Philadelphia’s history.

John Saillant is Professor of English and History at Western Michigan University. He is the author of the monograph Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University