Deafness and the Deaf

Essay

Documentation of the lives of deaf individuals in the Philadelphia region, and elsewhere, is limited. Historic accounts depict desperate individuals roaming the streets or begging. Prior to the advent of public schools for the deaf, only elite deaf individuals received private tutoring. In the early nineteenth century, Philadelphia philanthropists, religious figures, educators, merchants, and policymakers came together and created the city’s first school for the deaf. Their successes inspired other advocates to expand deaf education and services. Though later educators judged some of their efforts misguided, these pioneers demonstrated that the region’s impoverished deaf residents could also become productive citizens.

During the colonial era, only elite deaf children received much education, and it typically took the form of private instruction or tutoring. William Mercer (1765?–1839?), who was congenitally deaf, studied under the distinguished Philadelphia artist Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) after his father was killed in the Battle of Princeton. Peale and his wife, Rachel (1744–70), welcomed Mercer into their family of ten children from 1783 until 1786. Mercer was one of the first congenitally deaf individuals in the United States to become a distinguished artist.

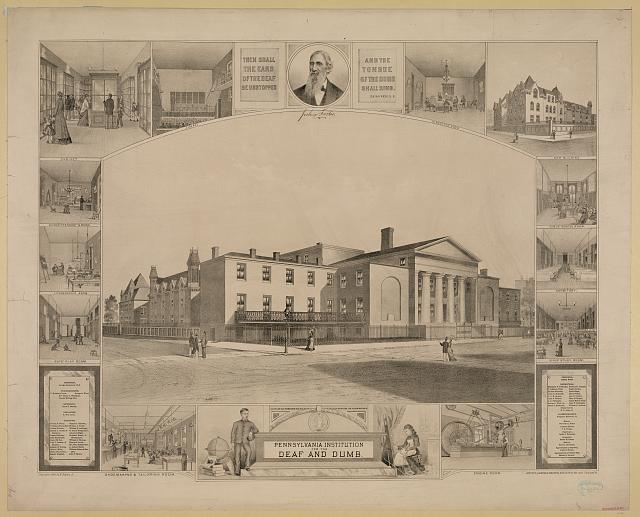

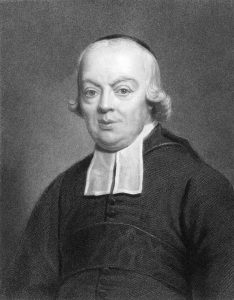

The Pennsylvania School for the Deaf in Philadelphia (formerly known as the Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb), the third-oldest school of its kind in the United States, was one of many that emerged in the early nineteenth century following the advent of deaf education in Europe. Public education for the deaf originated in France in the 1760s when Jansenist priest Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Epée (1712–89) created the National Deaf-Mute Institute in Paris, the world’s first public deaf school. His work eventually inspired deaf education programs in other nations, including the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf which began when David Seixas (1788–1864), a Philadelphia merchant and crockery owner, began to educate and provide room and board to a small group of local indigent deaf children.

The First Eleven

Moved by his concern for impoverished children whom he regularly witnessed roaming city streets, Seixas brought eleven poor deaf children into his home, where he fed, clothed, and educated them. Among the first group of children were future artists John Carlin (1813–91) and Albert Newsam (1809–64). Carlin, who became deaf as a young child, later studied portraiture in France under esteemed artist Paul Delaroche (1797–1856). He spent his adult life working as an artist and poet in New York, where he served as an activist for the deaf. Newsam, brought to Philadelphia from Steubenville, Ohio, in 1820 by William P. Davis, who allegedly convinced Newsam’s guardian to allow him to take the child to Philadelphia and intended to exploit the young boy’s artistic talent for his own gain, entered the school at age eleven after local Episcopal Bishop William White (1784–1836) found him on the streets and took him to Seixas’s home. There he received an education and developed his artistic talent. Newsam apprenticed with the local engraving firm of Cephas G. Childs (1793–1871) and eventually became a principal artist at the firm of Peter S. Duval (1805?–86).

Bishop White became intrigued by Seixas’s dedication to these poor deaf children and called for members of the American Philosophical Society to create a more permanent establishment. In May 1820, members of the society petitioned the Pennsylvania state legislature to officially recognize Seixas’s school, which it did in 1821. With the support of growing community interest and both philanthropic and state-sponsored funding, the institute officially opened at the corner of Eleventh and Market Streets in Philadelphia in the autumn of 1820 with Seixas as the institute’s first principal. Soon nearby states, including New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware, began sending their indigent deaf children there. Seixas was later dismissed from his post for alleged sexual misconduct with several female students. The Pennsylvania School for the Deaf eventually appointed Abraham B. Hutton (1798–1870) principal in 1830, and he remained in that position until his death.

Pedagogical shifts that focused on oralism, or training in the reading of lips, affected Philadelphia’s deaf community. Early efforts to instruct the deaf typically relied on the manual method, or sign language. In the 1870s, deaf education experienced a significant transformation as more programs began adopting the oral method. Educators throughout Europe and North America embraced oralism as the progressive approach to “normalize” the deaf and incorporate them into mainstream society.

In the late nineteenth century, sisters Emma (1846–93) and Mary Garrett (1854–1915) expanded services for the deaf in the region. Emma Garrett attended the program for teachers of the deaf at Boston University run by Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922), whose curriculum focused primarily on the oral method and on how to teach the deaf how to communicate and “behave” when interacting with the hearing community. After completing her education, Emma became a teacher at the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf and later served as principal of the Pennsylvania Oral School for Deaf-Mutes in Scranton. Like many deaf-education professionals of this period, she visited several countries to observe their teaching methods. Her observations of oralist methods, coupled with the widespread assumption that children (and especially deaf children) are incredibly imitative, led the sisters to establish an early intervention program in 1892.

The Bala Home

The Garretts established the Pennsylvania Home for the Training in Speech of Deaf Children Before They Are of School Age (also known as the Bala Home) at Belmont and Monument Avenues in Philadelphia. The school adopted a strict interventionist method that introduced the oral method at an early age. Emma served as superintendent of the institute until her death in 1893, when Mary assumed the post. Mary became a pioneer in the oral communication method as well as an advocate for the education of young women. She trained other notable educators of the deaf, including Margaret S. Sterck (1892–1984), who established the Delaware School for the Deaf in 1929, which remained active until 1945, when state regulations required that deaf children be taught in public schools.

After visiting oralist schools in other states, educators at the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf also shifted their program to include more training in the oral method. This decision reflected a broader international push for the method that had been adopted years earlier at the Milan Congress of 1880, where hearing delegates determined that sign language was a cumbersome form of communication and that the deaf should be taught to communicate in a “normal” way. In the decades following the Milan Congress, nineteenth-century pioneer in science Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922) advocated that schools throughout the United States and Europe adopt oralism, viewed as the progressive approach to “normalize” the deaf and incorporate them into mainstream society. The Pennsylvania School for the Deaf became one of the largest schools for the deaf in the United States. The widespread teaching of oralism later sparked controversy because it eventually led to the near elimination of sign language and disenfranchisement of the deaf community.

New advocacy groups such as the Pennsylvania Society for the Advancement of the Deaf, created in Philadelphia in 1881, also pushed to incorporate deaf individuals into society and maximize their potential. It was joined in the early twentieth century by such organizations as the Philadelphia League for the Hard of Hearing and the Speech-Reading Club of Philadelphia. Religious leaders contributed to helping local deaf populations as well. Concerned for his deaf parishioners, Archbishop Patrick Ryan (1831–1911) envisioned an institute that would serve the needs of deaf Catholics. While not realized until the year after his death, the Archbishop Ryan Memorial Institute for the Deaf, established first on Vine Street and then later moved to Thirty-Fifth and Spring Garden Streets and eventually to Delaware County, was named in his honor.

Sign Language Resurges

After nearly a century during which the oral method dominated, the study of sign language resurged in the late 1960s. After passage of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act in the 1970s, deaf schools nationwide employed a variety of educational methods. These approaches ranged from bicultural/bilingual education, in which American Sign Language is taught as a first language and written (or spoken) English is taught as a second language, to auditory-oral and auditory-verbal education. In the mid-1980s, Philadelphia schools adopted the more recent “mainstreaming” or inclusion model, in which deaf children attended public school for part of the school day while also receiving individualized deaf instruction. Programs such as the Clarke Schools for Hearing and Speech (located in Philadelphia and Bryn Mawr) later incorporated the “mainstreaming” model into their day school program. Critics argued that although this model provided inclusion and daily interaction with hearing individuals, deaf children found themselves isolated from other deaf individuals and received limited individualized support for special education needs.

Philadelphia played a significant role in the nation’s deaf education movement. The humanitarian project of a concerned citizen led to the creation of one of the nation’s largest and longstanding educational institutions for the deaf. In the early twenty-first century, the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf continued to serve deaf and hard-of-hearing children by offering a wide array of programs that served American Sign Language and English-language learning, as well as supported services and programming for students with cochlear implants. In 2013, St. Joseph’s University instituted a certification program to train teachers of the deaf and hard-of-hearing in 2013. Despite the strides in deaf education, however, mainstreaming programs remained the subject of debate over whether deafness should be categorized as a disability or as a condition to be “normalized.”

Holly Caldwell received her Ph.D. in history from the University of Delaware, where she wrote her dissertation on the medicalization of deafness and deaf education reform at Mexico’s Escuela Nacional de Sordomudos (National School for Deaf-Mutes). She is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of History at Chestnut Hill College and has also taught at Susquehanna University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University