Liberians and Liberia

Essay

Greater Philadelphia has had close links to Liberia historically. Free Blacks and abolitionists from the region helped colonize and underwrite the nation of Liberia’s founding in the early nineteenth century. Yet Philadelphia and Liberia had little connection between the mid-nineteenth and late twentieth century. Most Liberian settlement in the region resulted from the Liberian civil war of 1989-96 and 1999-2003, when people fleeing conflict were resettled as refugees but granted Temporary Protected Status. This produced a diverse Liberian community in the region, with active civil society organizations working to rebuild Liberia as well as resident communities in Philadelphia and its suburbs. By 2010, Greater Philadelphia was home to the largest Liberian community in the United States, and Liberians were the largest group of African immigrants in the region.

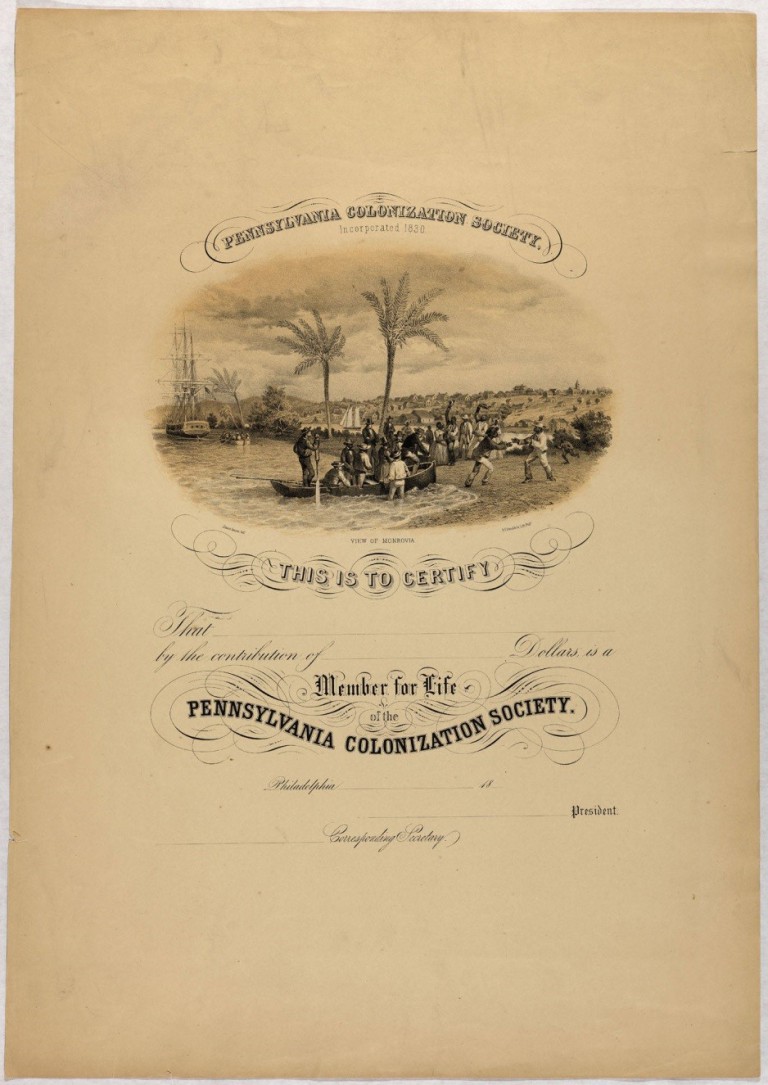

Liberia was established and colonized by free Black people from the United States, including some from the Philadelphia area, beginning in the 1820s. Some slaves in the United States came from the territories that became Liberia, though more came from neighboring Sierra Leone and Ghana. The colonization movement had deep ties to the Philadelphia area, though many of the region’s abolitionists condemned colonization and likened it to re-enslavement. Princeton native Robert Finley (1772-1817) founded the American Colonization Society, which underwrote and oversaw Liberia’s early development and the settlement of some thirteen thousand Black Americans. Its partner, the Pennsylvania Colonization Society, started in 1826 and in the early 1830s established Port Cresson (later Buchanan, Liberia), named for a society member and Philadelphia Quaker philanthropist, Elliot Cresson (1796-1854). At the bank of the St. John River, the settlement aimed to stem the outflow of more than one thousand slaves per month. Other partner institutions sponsored emigrants as well, including Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, which hosted two former slaves at its campus for training aimed at their migration to Liberia. The abolitionist and physician Martin Delaney (1812-85), who had been born free in Virginia, joined others in Pennsylvania pushing for emigration to Liberia into the 1860s, citing the poor prospects for Blacks in the United States and the imperative of creating a Black republic in Africa.

An independent nation since 1847, when it broke with the Colonization Society, Liberia had relatively little connection to the Philadelphia region from the late nineteenth until the second half of the twentieth century. As postcolonial African emigration took off in the 1960s, some middle class Liberians moved to Philadelphia and other parts of the United States to attend universities, including Temple, St. Joseph’s, and the University of Delaware. Many students returned home, but others stayed for a time. In the 1980s they formed the Union of Liberian Associations in the Americas (ULAA), with chapters in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Ohio, hosting social events and helping families cover funeral expenses.

Civil War Refugees

The Liberian civil war of the 1990s transformed the Liberian community in Greater Philadelphia and the U.S. Growing out of longstanding tension and exploitation by Americo-Liberians of the majority African population, the initial rebellion led by Caribbean-born Charles Taylor (b.1948) out of the American Firestone Tire Company rubber plantation ultimately spread to Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Ivory Coast. Liberians fled to neighboring countries, including Ghana, and to the United States, where many resettled as refugees. As one community leader noted, by the 1990s the Liberian population of Philadelphia and the U.S. was no longer “only college kids.” It had come to include people of varied ages, educational backgrounds, urban and rural origins, and personal and family problems resulting from the war. Liberians resettled in other U.S. regions also moved to Philadelphia, joining relatives and friends. By 2010, the U.S. Census counted roughly eight thousand Liberians in Greater Philadelphia, making up the largest nationality group among almost forty thousand African immigrants in the region. African community leaders estimated much higher numbers, including as many as fifteen thousand Liberians in Philadelphia and its suburbs.

A result of resettlement and of Black people’s segregation in American cities, most Liberians settled in working-class neighborhoods with other African and Caribbean immigrants and African Americans. Liberians of various education levels and occupations lived especially in West and Southwest Philadelphia, where a “Little Monrovia” formed along Woodland Avenue around Sixty-Sixth Street, and in nearby Delaware County suburbs including Colwyn, Darby, Upper Darby, and Lansdowne, as well as in Wilmington and Trenton. Like other African immigrants, Liberians worked a diverse range of jobs, from journalism, social work, and arts education to low-paid, irregular work as parking attendants, house cleaners, and home health aides, reflecting their bifurcation by class. Relative to other groups, in 2010, the median household income of Liberians in the region was $51,000, below the native-born in general ($72,000) but above African Americans ($35,000). Some 42 percent of Liberian households were homeowners (compared to over 70 percent of native-born households).

Liberians and Sierra Leoneans fleeing the civil wars in the 1990s and early 2000s were not accorded permanent refugee status and the ability to remain in the U.S. indefinitely, except in rare cases, although many were resettled through the federal refugee program by agencies like Philadelphia’s Nationalities Service Center and Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. Rather, the U.S. government granted them Temporary Protected Status, a designation for people from countries, typically at war, where refugee agencies expect displaced people will be able to return when conditions improve. The federal government allowed Liberians’ Temporary Protected Status to expire in 2007, placing them on Deferred Enforced Departure, a status renewable by the White House every twelve or eighteen months, but granted Temporary Protected Status again during the Ebola epidemic of 2014. Liberian community leaders and Philadelphia City Council, at the urging of West Philadelphia Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell (b.1945), regularly lobbied for renewing both statuses, with counterparts in other U.S. regions and Liberia. Under both statuses, Liberians received work permits, but under Deferred Enforced Departure they were not eligible for federal financial aid and could not leave the country. The impermanent nature of both statuses created instability in the lives of many Liberians, though many also attained permanent residency and some became U.S. citizens.

Like other refugees fleeing civil war, Liberians experienced a variety of trauma, compounded by resettlement and life in largely segregated and impoverished neighborhoods and schools of working class neighborhoods. Some Liberian residents of Philadelphia and Delaware County were charged as war criminals, and many testified from Philadelphia as witnesses of episodes in the war for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia, assisted by the Transnational Law Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania. People from the fifteen counties of Liberia, associated with different sides and events in the war, lived in Greater Philadelphia, meaning that sometimes in the supermarket or on the street Liberians encountered countrymen responsible for the deaths of their family members during the war. Liberian and other Black immigrants have also experienced tensions with one another and with African Americans. The most publicized event occurred in 2005, when a 13-year-old Liberian boy was attacked and his skull fractured by African American youth on his way home from school in Southwest Philadelphia. To protect themselves from such attacks, Liberian high school students in the region and nationally formed a gang named LIB.

Civil Society

In response to these and related challenges, Liberians developed a vibrant set of community organizations. The African Cultural Alliance of North America (ACANA), formed in 1999 and based in Southwest Philadelphia, became the largest African immigrant-run social service, arts and culture, and community development nonprofit in the region. Its annual festival at Penn’s Landing has drawn thousands of people each summer, while its adult education, youth anti-violence, health and wellness, and legal services programs have addressed a range of needs among African, Caribbean, and African American constituents in the region. ACANA partnered with Project Tamaa of the Children’s Crisis Treatment Center to serve young Liberians, Sierra Leoneans, and Guineans and their parents and teachers dealing with trauma. Another organization, Multicultural Community Family Services, founded in 2003 and based in Upper Darby, has run job readiness programs, a soccer league, and other community services especially for youth from Africa, Latin America, Asia, and the United States. The Agape African Senior Center in West Philadelphia, established in 2000 by a reverend from Liberia, has offered English classes, orientation to the neighborhood, and other basic supports for refugees and immigrants.

Other organizations in the region reflected the diversity of the Liberian community and its strong connections to other immigrant and receiving communities. These included professional and alumni associations, such as the Association of Liberian Journalists, Association of University of Liberia Alumni in the U.S.A., and Monrovia College Alumni Association in the Americas. Liberians played key roles in founding Philadelphia’s two most important Pan-African organizations, the Coalition of African Communities in Philadelphia (AFRICOM, established 2001) and the Mayor’s Commission for African and Caribbean Immigrant Affairs (established 2008). The Mayor’s Commission helped organize trade missions, including visits by Philadelphia area entrepreneurs and officials to Liberia as well as hosting Liberian dignitaries in Philadelphia.

Some Liberians who came to Philadelphia in the 1990s were prominent performing artists. Refugee resettlement caseworkers bemusedly recounted the story of waiting at the airport for a refugee couple, only to be told by the husband when they arrived that his wife, a famous singer, had booked tour dates around the United States and had a connecting flight, so could not accompany the caseworkers to the apartment they had arranged for the couple. The Philadelphia Folklore Project, based in Southwest Philadelphia, has supported Liberian dancers and musicians, as has ACANA. The Folklore Project helped former members of the Liberian National Cultural Troupe establish the activist Liberian Women’s Chorus for Change.

In addition to their local activities in Greater Philadelphia, many Liberian community organizations have worked transnationally to rebuild and remain connected to Liberia. The ULAA and members of its Pennsylvania chapter have been deeply engaged in the reconstruction of Liberia’s national government and civil society, supporting democratic elections and reforms. Immigrants and refugees from each of Liberia’s counties formed a nonprofit county association in the U.S., in which Liberian community leaders in Philadelphia have been active. The county associations have provided scholarships for school and university students in Liberia; helped finance, plan, and build schools, medical clinics, and roads, water, and telecommunications infrastructure, usually in collaboration with county governments; sent medical and school supplies; and launched agricultural enterprises. In these ways, Liberians in Greater Philadelphia have worked to revitalize the towns, counties, and nation of Liberia, as well as the city and suburban neighborhoods in which they settled.

Domenic Vitiello is Associate Professor of City Planning and Urban Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and an associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. He has been a member of AFRICOM, served on the board of the African Cultural Alliance of North America, and refereed the annual African Communities Soccer Tournament in Philadelphia and Delaware County. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University