Pirates

By Tim Hayburn

Essay

Philadelphia, like many cities throughout the Atlantic world, encountered a new threat in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries from pirates who raided the numerous merchant vessels in the region. Several historians have labeled this era as the golden age of piracy. Pirates also remained active after 1730, using the city as a staging ground, especially during conflicts such as the Revolutionary War. While Pennsylvania authorities sought to end piracy throughout the colonial and early national periods, their policy appears ambivalent as they sometimes extended leniency toward pirates rather than confront them with the full force of the law.

Pirates were outlaws on the sea who attacked all ships, regardless of their nation of origin. They plagued shipping routes, which had at times a devastating effect on trade in Philadelphia. Many pirates first served as privateers, who were employed by nations such as England as alternatives or in addition to a formal navy during times of war. Privateers received a letter of marque, or commission, to raid enemy ships. When the conflicts came to an end, however, many of the privateers became pirates, continuing to rob ships of their cargoes, which the pirates shared.

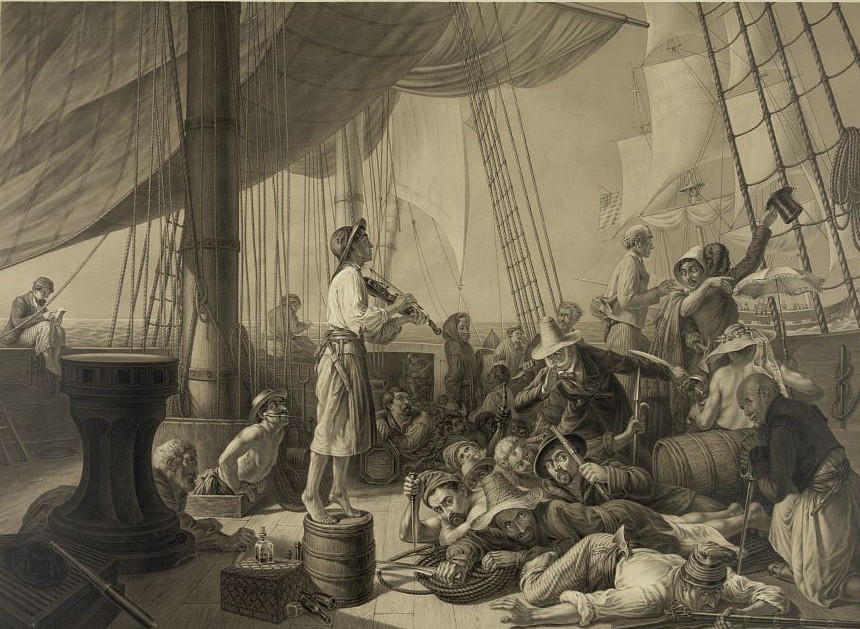

Soon after Philadelphia’s founding, the city’s growing population and economic importance attracted pirates who threatened the region’s thriving trade. Piracy offered local sailors the opportunity to earn higher profits and benefits that they would not receive on merchant or naval vessels. Life on board pirate ships tended to be much more democratic than on other ships as pirates could even depose an unpopular captain and discipline was much more lax.

Pirates regularly operated around the Delaware River by the late seventeenth century, which fueled fears about the safety of the local waterways. In 1699, the colony arrested four men believed to serve under the notorious pirate Captain William Kidd (c. 1645-1701). The Pennsylvania Assembly enacted several statutes to prevent pirates from moving freely in society and to keep others from collaborating with them. Some merchants in the Delaware Valley willingly tolerated piracy, however, because of its economic benefits. Pirates spent their booty freely in port cities such as Philadelphia and contributed to the region’s economic development. William Markham (1635-1704), Pennsylvania’s deputy governor, even allegedly received a bribe from the pirate John Avery (1659-c. 1696), who raided ships throughout the Indian Ocean and was subject to an English manhunt. Markham’s relationship with Avery extended beyond simply accepting a bribe as he also allowed one of his daughters to marry the infamous pirate captain.

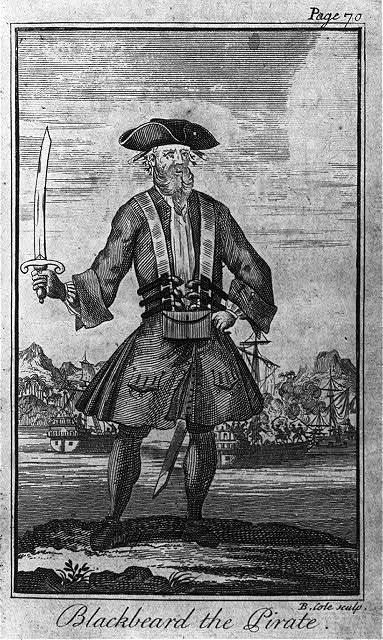

Piracy continued to be a major concern for many merchants in the early 1700s, despite the unofficial toleration of some officials and the potential benefits of piracy for some segments of the Delaware Valley economy. Lieutenant Governor William Keith (1669-1749) issued a warrant for the arrest of Edward Teach (c. 1680-1718), better known as Blackbeard, for his attacks on merchant ships. Keith feared that Blackbeard maintained contact with former pirates, who now lived in Philadelphia and aided him in his raids against Philadelphia’s merchants. The local newspaper provided periodic reports of pirate activity in the Philadelphia region by the early 1720s. Pirates even managed to prevent ships from leaving Philadelphia for an entire week in 1722. The Pennsylvania Assembly sought to eliminate property crimes such as robbery by making them subject to capital punishment, which could be used in cases against pirates.

A Trial for Piracy

Perhaps because local authorities realized the financial contribution of pirates to the region, Philadelphia witnessed only one trial for piracy in the first half of the eighteenth century. In 1730, English sailors serving on board a Portuguese ship mutinied and became pirates before finally being arrested and condemned to death in Philadelphia. During an era when pirates could hope for little mercy, four of these condemned pirates surprisingly received a pardon from Pennsylvania authorities after their ringleader escaped. Indeed, many Philadelphians may have supported pirates, as testimony in a 1718 case alleged that Pennsylvania merchants provided pirates with ammunition and supplies.

After 1730, piracy ceased to be a major problem for Philadelphia although privateers occasionally disrupted the city’s shipping. Both colonial officials and the British government sought to reduce the threat of piracy. The Revolutionary War, however, allowed for a resurgence of pirates by the 1780s. When the Continental Congress employed privateers to supplement its meager naval forces, several crews turned to piracy. Local newspapers complained about these “villains” who disrupted the Revolutionary War effort, but Pennsylvania’s courts condemned only four men for piracy in the 1780s. One condemned pirate was even sentenced to have his body gibbeted to deter other potential pirates. Nevertheless, Pennsylvania’s government again surprisingly opted for leniency in his case as well as most of the other condemned pirates and executed only one convicted pirate during this time.

By the 1790s, the Pennsylvania legislature removed piracy from the list of capital crimes. Cases of piracy declined into the nineteenth century. The state did witness several cases of piracy in the early nineteenth century, but applied the death penalty only in cases in which the pirates committed murder as well. Indeed, in 1837, convicted pirate James Moran was the last individual publicly executed in Pennsylvania for any crime. Although Philadelphia merchants could occasionally fall victim to pirates in other corners of the globe such as the Mediterranean Sea, piracy ceased to be a major concern in the Delaware Valley, thus ending Pennsylvania’s ambivalent policy towards piracy as well.

Tim Hayburn received his doctorate in Colonial American History from Lehigh University.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History