U.S. Presidency (1790-1800)

Essay

Although the federal government under the U.S. Constitution went into operation in New York City in April 1789, the capital moved to Philadelphia late in 1790 and remained until 1800. This decade encompassed formative years for the U.S. presidency, including nearly seven years of the administration of George Washington (1732-99) and more than three years of the single term of John Adams (1735-1826). Among other notable events, Philadelphia witnessed Washington’s second inauguration and John Adams’s inauguration, significantly the first transfer of power from one president to another.

Washington took up residence in Philadelphia in December 1790. For his executive mansion, he rented from the city for 500 pounds a year the house of Robert Morris (1734-1806) at 190 High Street (526-30 Market Street today) near the corner of Sixth Street. One of the largest homes in the city, the President’s House (as it became known) stood three stories tall and featured a spacious backyard with several outbuildings including a wash house, kitchen, ice house, smoke house, coach house, and stables. Amenities also included a walled garden, a paved yard, and a wood yard. Before moving in, Washington had a two-story bow added to the southwest corner of the house to enlarge the State Dining Room and State Drawing Room, and also built slave and servant quarters in the backyard. In addition to one or two secretaries, a staff of about a dozen white servants plus three or four enslaved African Americans from Mount Vernon served the president’s family, which included Martha Washington (1731-1802) and two of Martha’s grandchildren, Eleanor “Nelly” Parke Custis (1779-1852) and George Washington Parke Custis (1781-1857). Washington regularly rotated his slaves out of Pennsylvania to keep them from becoming free through the state’s 1780 Gradual Abolition Act, which freed nonresident slaves who had lived there continuously for six months. Enslaved seamstress Ona Judge (1773-1848) fled to freedom from the city, while a cook named Hercules (b. ca. 1754) escaped on Washington’s birthday in 1797 after returning to Mount Vernon.

Washington enjoyed Philadelphia’s amenities (especially the theater and the shops) and admired the industrious economy of the middle states more than he did the slave-based economy of the South. But Washington thwarted the hopes of Philadelphians by ensuring the capital’s removal to Washington, D.C., in 1800. He did this by declining to occupy an immense residence built by the city on Ninth Street and by pushing forward construction of the new capital on the Potomac River.

Social Life at the President’s House

Entertainments at the President’s House consisted of Tuesday afternoon “levees,” Thursday afternoon state dinners, and Friday evening “drawing rooms” that Martha Washington hosted and her husband informally attended. At the levees, Washington appeared in formal dress, stood in the bow of the State Dining Room, and exchanged greetings with gentlemen attendees formed in a circle. “On fryday Evenings mrs. Washington has a drawing Room which is usually very full of the well Born and well Bred,” wrote Abigail Adams (1744-1818). “Some times it is as full as her Britanick majesties Room, & with quite as Handsome Ladies.” The “company are entertained with Coffee Tea cake Ice creams Lemonade &c…this shew lasts from seven, till Nine oclock comeing & going…as it is not Etiquette for any person to stay Long.” Wealthy Philadelphians such as Samuel Powel (1738-93) and his wife Elizabeth Willing Powel (1743-1830) also hosted a variety of parties for socializing and political networking, forming what became known as the “Republican Court.” Abigail Adams witnessed “Parties upon Parties, Balls & entertainments” in Philadelphia “equal to any European city.”

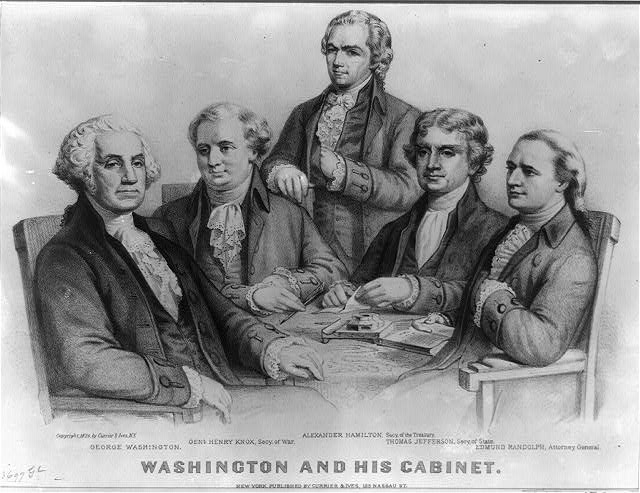

In Philadelphia, President Washington continued the challenging task of establishing presidential precedents that he had begun in New York. For example, he conferred with his department heads— Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Secretary of War Henry Knox (1750-1806), and Attorney General Edmund Randolph (1753-1813)—as a group advisory board that became known as the cabinet. Washington issued the first presidential veto in 1792 when he rejected a bill to reapportion congressional representation.

Philadelphia witnessed the emergence of political parties, with Washington endorsing the use of implied powers and loose construction of the Constitution advocated by Hamilton and the Federalist Party to create a strong federal government and to promote an industrial economy. In 1791, for example, he signed the controversial bill creating the Bank of the United States (the institution moved into its home on Third Street in 1797). The opposition Republican Party led by James Madison (1751-1836) and Jefferson favored an agrarian republic of limited federal power and feared that the administration’s “high toned” policies foreshadowed a return of monarchy to America. Washington, who deplored partisanship and who viewed parties as special interests hostile to the public good, tried unsuccessfully to reconcile cabinet members Hamilton and Jefferson. In response to pleas from both parties, Washington reluctantly accepted a second term as the new nation’s president starting in 1793.

Fleeing Yellow Fever

When, in the summer and fall of 1793, a yellow fever epidemic killed ten percent of Philadelphia’s residents, the Washingtons safeguarded themselves by traveling to Virginia. After returning to the city in November, the president moved his residence to Germantown, first to the Dove House and then to the Deshler-Morris House. The following summer, the Washingtons occupied the latter home to escape the heat of the city.

President Washington sought to evict British forces from posts in the Northwest Territory, to provide western farmers with protection from Indian attacks, and to obtain the right from Spain for Americans to navigate the Mississippi River. He sent military expeditions against the Northwest Indians led by Josiah Harmer (1753-1813) in 1790 and Arthur St. Clair (1737-1818) in 1791 that ended in disastrous American defeats. The latter loss led to the first congressional investigation of the executive in U.S. history. A third expedition led by Anthony Wayne (1745-96) defeated the Indians in 1794 at Fallen Timbers in present northwestern Ohio. The administration negotiated peace treaties with the southern Indians, and secured the right to navigate the Mississippi River from Spain in 1795.

Frontier farmers, angry over a 1791 federal excise on whiskey, both a staple drink and a form of currency in the region, defied the tax and harassed revenue collectors in four western Pennsylvania counties near Pittsburgh. After Washington’s attempts to redress grievances failed to subdue the uprising, in 1794 he federalized 13,000 militiamen from New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, establishing a precedent that President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) followed in 1861 to resist the secession of the southern states.

Hoping to steer clear of war between Great Britain and France, Washington issued the 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality. The following year he appointed John Jay (1745-1829) a special envoy to Great Britain to negotiate an end to British seizures of American ships and impressment of sailors. Washington signed the controversial Jay Treaty in 1795 even though it did not end ship seizures and impressment, because he was determined to keep the new nation at peace. Mobs celebrating the French Revolution and critical of the agreement soon roamed the city and even threatened the president’s safety. A major dispute between the executive branch and the Republican-controlled House of Representatives occurred when Washington refused to turn over sensitive documents pertaining to the treaty negotiations, citing executive privilege. By holding political gatherings and public meetings to rally public opinion behind the president, the Federalists pressured the House of Representatives into appropriating funds to implement the treaty. In exploiting Washington’s popularity to win the battle over the treaty, however, the Federalists unleashed democratic forces in American politics that lost them the war for control of the federal government when the Jeffersonian Republicans won the election of 1800. The Republicans, whose democratic ideology proved more appealing to common voters than the deferential, aristocratic ideology of the Federalists, also began seeking support directly from the voters on specific issues.

Washington’s Farewell Address

On September 19, 1796, Washington’s Farewell Address announced that he would not serve a third term as president. A printed message, not a public speech, the farewell appeared in the Philadelphia American Daily Advertiser published by David C. Claypoole (1757-1849). In addition to warning against entangling foreign alliances, the address called on the American people to place national interests and the common good ahead of political partisanship.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were sworn in as the second president and vice president, respectively, at Congress Hall on March 4, 1797. This first transfer of executive power marked a great triumph for the new republic and a milestone in the history of representative democracy. By choosing to occupy the High Street house (despite a doubling of the rent and the building’s severe state of disrepair) rather than the palace on Ninth Street, Adams helped guarantee the removal of the capital to Washington, D.C., in 1800. Adams hosted weekly “great dinners,” each attended by about “36 Gentlemen,” as well as Fourth of July celebrations.

Adams, like Washington, admired Philadelphia. “It is a great City,” he wrote, “and has Science, Literature, Wealth and Beauty.” But he found the presidency even more trying and disagreeable than his predecessor, and spent much of his term at home in Massachusetts with his wife, Abigail, who suffered poor health.

Faced with French anger over the Jay Treaty, Adams sent diplomats to Paris to seek a peaceful resolution. Instead, the envoys received an insulting demand from the French for a bribe. This failure of diplomacy led to the Quasi-War in 1798, an undeclared naval war with France on the Atlantic Ocean. Republican opposition to a military buildup, the presence in Philadelphia of hundreds of French refugees fleeing the slave rebellion in Haiti, and vicious attacks on Adams in the partisan press convinced the Federalists in Congress to pass, and Adams to sign, the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws made it a crime to falsely or maliciously criticize the president or Congress, authorized the president to deport aliens without due process, and increased the residency requirement for U.S. citizenship from five to fourteen years. The unpopularity of these acts, tax increases caused by the military buildup, and an ongoing divide between the Adams and Hamilton factions in the Federalist Party, intensified by the president’s decision in 1800 once again to try to negotiate peace with France, contributed to the 1800 defeat of Adams and the Federalists by Jefferson and the Republicans.

Early in the nineteenth century the President’s House, located in a thriving commercial neighborhood, was converted into shops. All but the side walls of the building were knocked down in 1832 to accommodate bigger stores. Early in the twentieth century, confusion arose over the exact size and location of the President’s House. In 1951, the state of Pennsylvania, not realizing the historical significance of the site, demolished the surviving exterior walls of the building to clear land for Independence Mall, and then erected a restroom on the site. In 2000, the ice house pit was unearthed while building the Liberty Bell Center. The ironic location of the quarters of Washington’s slaves near the entrance to the Liberty Bell Center drew considerable public attention. Archaeologists excavating the site in 2007 discovered significant portions of the original foundations. Beginning in 2010, visitors to the President’s House Site (an open air exhibit within Independence National Historical Park) could view the building’s original footprint and underground remains.

Philadelphia hosted perhaps the most pivotal decade in the evolution of the presidency, during which the emergence of an independent but democratic chief executive set the stage for Thomas Jefferson’s Revolution of 1800.

Stuart Leibiger is a Professor and History Department Chair at La Salle University. He is the author of Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic (University of Virginia Press, 1999) and editor of a Companion to James Madison and James Monroe (Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- The President's House Site (Independence National Historical Park)

- The President's House in Philadelphia (USHistory.org)

- The President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation (Visit Philadelphia)

- Reopening a House That's Still Divided (New York Times, December 14, 2010)

- Ten Facts About Washington's Presidency (MountVernon.org)

- George Washington, the Reluctant President (Smithsonian Magazine, February 2011)

- John Adams (WhiteHouse.gov)

- John Adams, Second President of the United States (John Adams Historical Society)

- Case Study: The President's House

- George Washington Digital Encyclopedia (Mount Vernon)