Trenton and Princeton Campaign (Washington’s Crossing)

Essay

One of the most significant events in the Revolutionary War was the Continental Army’s December 25, 1776, crossing of the Delaware River, led by General George Washington (1732-99), which preceded three crucial American victories—two at Trenton and one at Princeton, New Jersey—that reignited the virtually extinguished Patriot cause. Immortalized in the famous 1851 painting by Emanuel Leutze (1816-68), the crossing has become one of the most commemorated scenes in American iconography. The campaign enabled the rebel militia to reclaim most of New Jersey from the British and their Loyalist allies, helped the Continental Congress to recruit new fighting forces, and boosted public confidence in the commander-in-chief.

During the fall of 1776, British troops under General William Howe (1729-1814) forced the Continental Army to evacuate Manhattan and to retreat southwest across New Jersey. Numbering about 3,000 men, Washington’s shattered army escaped across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania on December 7, with the British in pursuit. The Continental Congress, fearing an enemy occupation of Philadelphia, fled to Baltimore. Howe, hoping to pacify New Jersey, spread his forces into seventeen outposts across the state.

After first making his headquarters at Summerseat, the home of Thomas Barclay (1728-93) in Falls Township across the Delaware from Trenton, Washington a week later relocated ten miles upriver to the Keith House near McConkey’s Ferry in Upper Makefield Township. Washington deployed his men to guard the crossing points above and below Trenton as best they could, and ordered Continental forces still in New Jersey under generals Charles Lee (1732-82) and Horatio Gates (1727-1806) to reinforce him. Since the previous August, Washington had suffered a string of devastating defeats, had lost ninety percent of his men to battle casualties, desertion, and sickness, and lacked clothing and supplies for the few who remained. Nevertheless, he resolved to strike before expiring enlistments completely dissolved his army—and ended the revolution—at the end of the year. Recognizing an opportunity to achieve numerical superiority over the Hessian garrison of Colonel Johann Rall (1726-76) in Trenton, Washington decided to recross the river and attack. Meanwhile, New Jersey militia under General Philemon Dickinson (1739-1809) waged hit-and-run attacks that left the Hessians nervous and weary.

Three-Pronged Attack

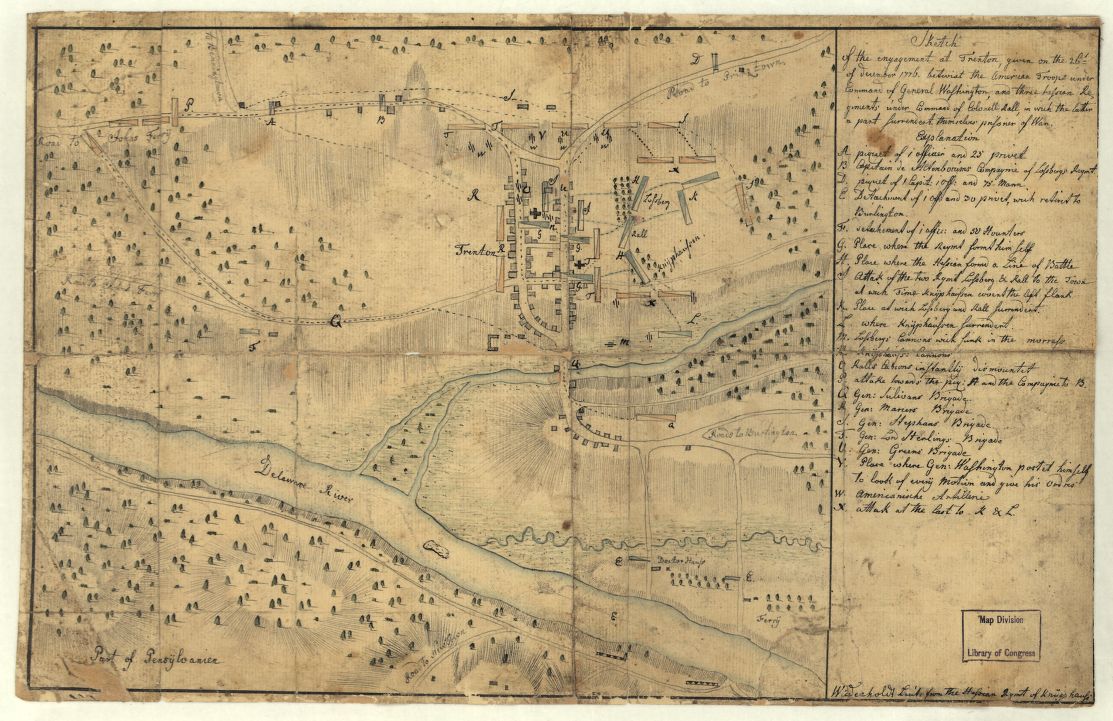

Washington planned a three-pronged crossing of the river for the night of December 25, to be followed by an attack on Trenton before sunrise. Contrary to myth, he did not strike on the day after Christmas because he expected the Hessians to be drunk from holiday revelry. Instead, he moved as soon as possible. Washington’s forces would cross the river at McConkey’s Ferry and hit Trenton from the north, while General James Ewing (1736-1806) of the Pennsylvania militia would cross with 700 men from Falls Township to the Assunpink Creek south of Trenton, to prevent the Hessians from escaping. The third prong, consisting of Philadelphia militia known as “The Associators” commanded by Colonel John Cadwalader (1742-86), would cross from Bristol, Pennsylvania, to Burlington, New Jersey, to stop Hessians under Colonel Carl von Donop (1732-77) from aiding Rall.

On the night of December 25, an ice-clogged river and a violent nor’easter featuring rain, hail, and snow delayed Washington’s crossing of the Delaware by four hours. Marblehead, Massachusetts, fishermen under Colonel John Glover (1732-97) ferried the army across using large Durham boats designed for carrying iron ore down the river. So severe were the conditions that neither Ewing nor Cadwalader could cross the river. Having been warned to expect a midnight attack, the enemy lowered its guard at dawn, shortly before 2,500 Continentals launched a weather-delayed assault. Although taken by surprise, the Hessians might have withstood the offensive had Rall not been mortally wounded. The Continentals killed or wounded 106 Hessians and captured 916 more without suffering a fatality. The victorious army and its prisoners recrossed the river back to Pennsylvania at McConkey’s Ferry.

Unaware of these developments, the Associators crossed on December 27 into New Jersey, where Cadwalader urged Washington to join him to renew the offensive. Persuading about half of his men to reenlist with a cash bounty of ten dollars, Washington on December 31 reoccupied Trenton, where he was joined by Cadwalader and Ewing. On the evening of January 2, the Continentals resisted probing attacks waged by Redcoats under General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) in the Second Battle of Trenton. Rather than risk annihilation when the fighting resumed in the morning, Washington instead slipped south out of town during the night. Turning east and then north, the Continentals marched through Quaker Bridge towards Princeton to attack another British outpost under General Alexander Leslie (1731-94). Instead they intercepted and routed an enemy regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood (1729-80) headed for Trenton, as well as two additional regiments coming out of Princeton. After flirting with the idea of attacking yet another British outpost at New Brunswick, Washington took his weary men into winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey.

Ten-Day Turnaround

In ten days, Washington’s three victories—two at Trenton and one at Princeton—turned the 1776-77 campaign around. To prevent further attacks against his vulnerable outposts, General Howe consolidated his forces in New Jersey, allowing Whigs to reassert themselves and leaving his pacification campaign in ruins. The victories lifted American spirits sufficiently to recruit additional forces to carry on the war. During the campaign, Washington, along with his officers, demonstrated charismatic leadership and moral courage. The commander-in-chief also gained confidence in himself, won newfound respect from his men, and shattered the belief in British invincibility. With the British threat no longer imminent, Congress returned to Philadelphia in March 1777 and remained there until Howe captured the city in September of that year.

State historical parks on the New Jersey and Pennsylvania shores of the Delaware River commemorate the Crossing, while The Trenton Barracks Museum and Princeton Battlefield State Park interpret the three American victories.

Stuart Leibiger is a Professor and History Department Chair at La Salle University. He is the author of Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic (University of Virginia Press, 1999) and editor of A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe (Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Retracing a well-worn path across the Delaware River (WHYY, December 23, 2011)

- The crossing of the Delaware you haven't heard about (WHYY, December 24, 2012)

- Washington Crossing reenactors strive for authenticity (WHYY, December 6, 2013)

- Mission to preserve Revolutionary War site in Princeton enlists further support (WHYY, November 11, 2014)

- Out from the crossing's shadow, Battle of Princeton gets re-enactment of its own (WHYY, January 2, 2015)

- National preservation groups enlist in fight over Princeton Battlefield (WHYY, March 4, 2016)

- Legal fight continues over Revolutionary War battlefield (WHYY, April 12, 2016)

- Conflict over Princeton Battlefield ends with deal to save bulk of tract from development (WHYY, December 13, 2016)

Links

- Washington Crossing Historic Park

- Battle of Trenton (BritishBattles.com)

- The Princeton Battlefield Society

- Princeton Battlefield State Park

- Washington Crossing The Delaware Redux (ABC News, December 27, 2011)

- The Re-enactment of Washington Crossing The Delaware (Bob Krist, December 12, 2010)

- Ten Days That Shook the World: Washington's Crossing (YouTube)