Democratic-Republican Societies

Essay

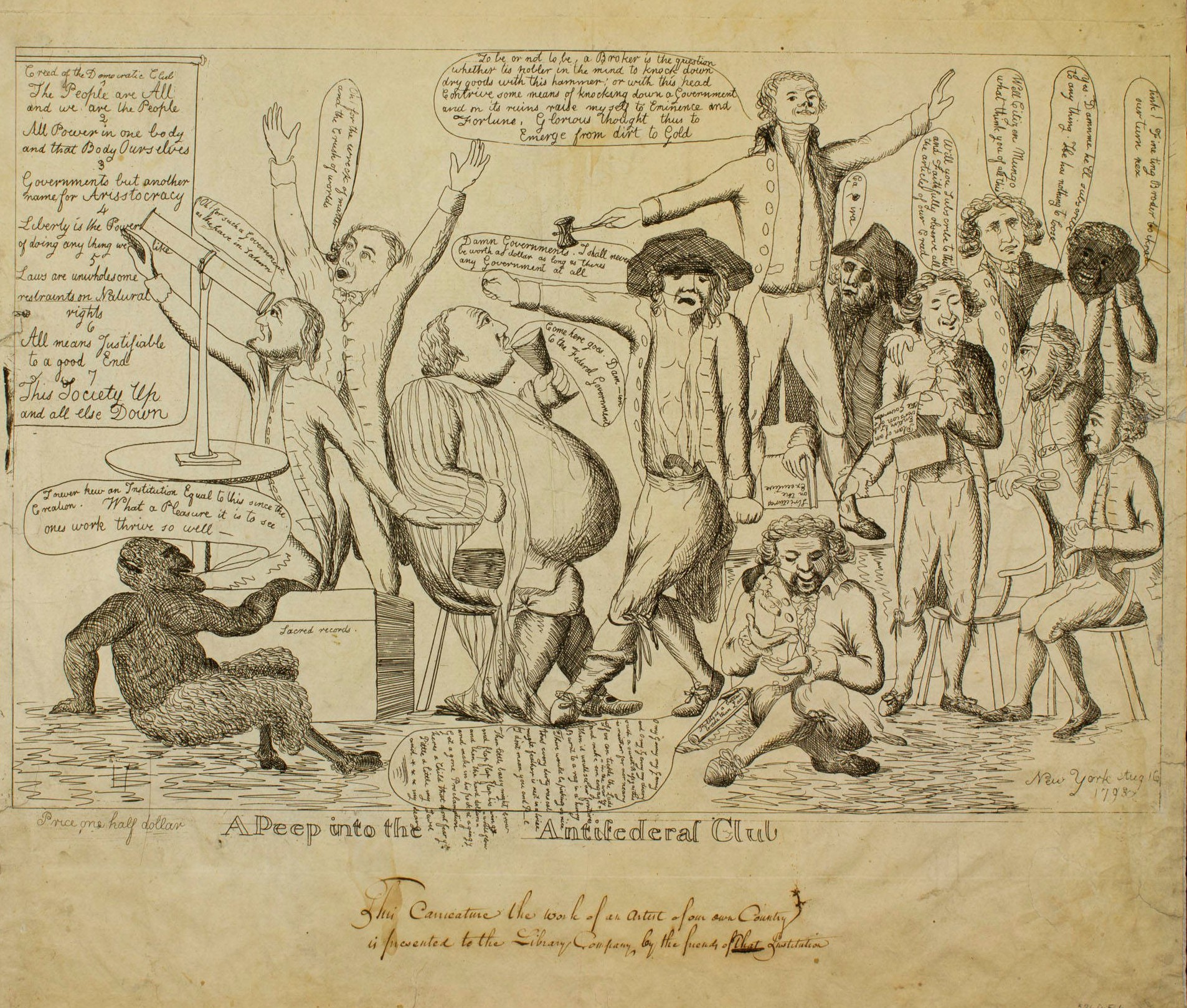

In the 1790s the Democratic-Republican Societies emerged and helped to establish the precedent in the United States for political organization and government opposition at the local and regional level. In April 1793 in Philadelphia, then the capital of the United States, Peter Muhlenberg (1746-1807) and Michael Leib (1760-1822) founded the first of these societies, the German Republican Society of Philadelphia. Over the next two years, six more societies organized in Pennsylvania, while others, numbering forty-two at their height, appeared nationwide from Massachusetts to Georgia.

Designed by their founders to scrutinize government actions, the societies saw themselves as overseers of republican virtue, harkening back to the ideals of the American Revolution. They supported revolutionary France and stood ready to guard against corruption in the state and federal governments. The German Republican Society and the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania, which formed in May 1793 in Philadelphia, involved themselves in many political issues of the early 1790s such as the new federal excise tax (1791), the Proclamation of Neutrality (1793), and the Jay Mission to Great Britain (1794) to rally their followers and point out differences between themselves and the Washington administration. Opposing these issues gave the societies a forum by which they could publicly criticize the administration, holding up to the public the dangers of a government that neglected the needs or interests of the people, while promoting their own candidates for political office. Thus, the societies attacked the administration for both ideological and practical reasons.

Through letters published mainly in the National Gazette and the General Advertiser, the German Republican Society explained that it had been formed for “republican purposes.” It emphasized the need for every citizen to participate in the affairs of state by taking part in government at the local level and guarding against corruption. The German Republican Society also saw itself as a vehicle for promoting public discussion and educating the German population in the affairs of state. Its formation illustrates the growing German influence in Philadelphia and national politics in the 1790s. In mid-1794 the German Republican Society and the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania merged because they believed working together would better serve their common goals and interests.

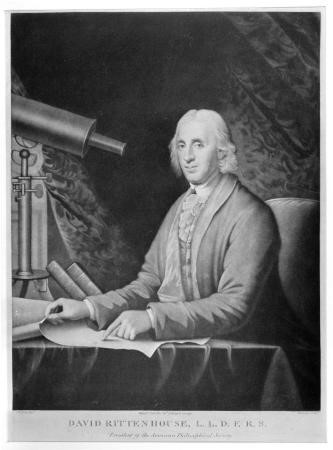

The largest society in the nation, the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania had a membership that topped three hundred. Composed mostly of craftsmen, merchants, and manufacturers, leadership in the society came predominantly from public officials, merchants, printers, lawyers, and doctors. Many prominent Philadelphians, such as David Rittenhouse (1732-96), George Logan (1753-1821), and Alexander James Dallas (1759-1817), became officers in the society.

Through letters, proclamations, resolutions, and toasts, members of the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania first used their support for the new French republic to define differences between themselves and the Washington administration. The society’s opposition to the federal excise tax initially unified the Philadelphia-based society with those in the western part of the state, but when western societies became linked to the violence of the Whiskey Rebellion in July 1794, the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania tried to disassociate itself from the uprising, and from those who participated in it.

The Washington administration used this opportunity to publicly condemn all Democratic societies. The administration’s ridicule of the societies as fomenters of rebellion certainly contributed to the demise of the Democratic-Republican Societies nationwide and in Pennsylvania. By 1796 the Democratic Society of Pennsylvania had disbanded. The Democratic societies had built a framework on which the emergent Democratic-Republican movement could build to oppose the tide of Federalism. Additionally, many of the former leaders within the Democratic societies took on new leadership roles within the Democratic-Republican Party.

A new group, the True Republican Society of Philadelphia, organized in 1797, is considered by some historians as an extension of the defunct Democratic Society of Pennsylvania. The True Republican Society did not become active until the Democratic-Republicans had coalesced into a party, however, and consequently most of its public pronouncements appeared after the turn of the century. The society’s activities centered on supporting Republican candidates for office, whereas the earlier Democratic-Republican societies acted strictly to disseminate republican sentiments and to inform the public of corruption and anti-democratic policies.

The Democratic societies had set a precedent for political opposition that the newly formed Democratic-Republican Party developed further. Therefore, the Democratic-Republican societies based in Philadelphia contributed to and helped establish the long tradition, in the United States, of political opposition through grass-roots societies.

Jeffrey A. Davis, Ph. D., is Professor and Chair in the History Department at Bloomsburg University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History