Roosevelt Boulevard

Essay

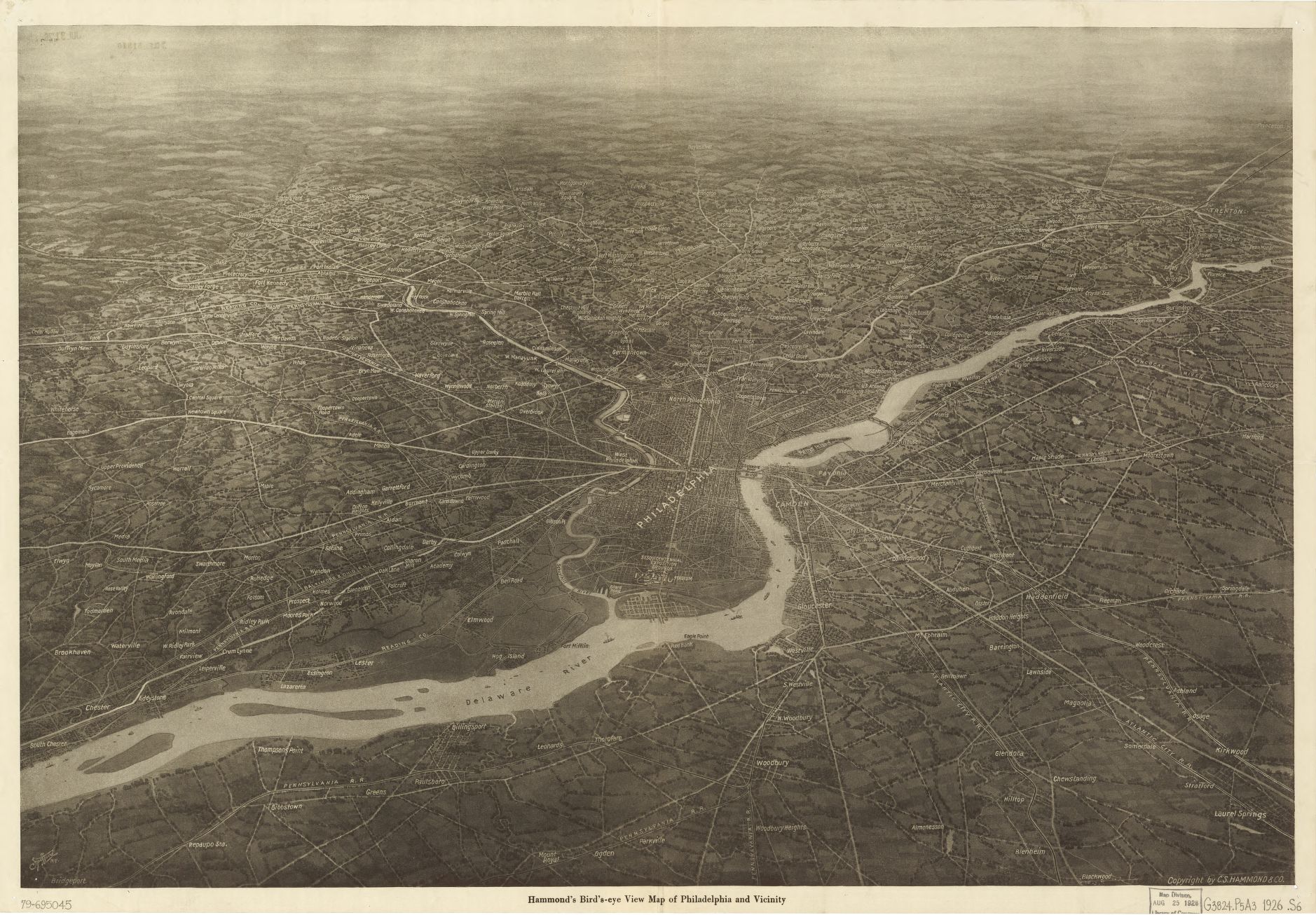

Snaking its way through parts of North and Northeast Philadelphia, the Roosevelt Boulevard, formally known as the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Boulevard, has become one of the most heavily traveled thoroughfares in the Philadelphia metropolitan region. Initially conceived amid political maelstroms during the “corrupt and contented” phase of Progressive Era Philadelphia, “the Boulevard,” as it became known, evolved in phases and embodied the complicated planning and political factors, especially following World War II, that went into its convoluted and still unsettled development.

The Boulevard’s history dates to 1902 when, in a bold effort to continue binding the commercial interests of downtown Philadelphia with the largely untrammeled and unoccupied lands of Northeast Philadelphia following the Act of Consolidation (1854), the mayoral administration of Samuel Ashbridge (1848-1906) called for building a modern transportation link to facilitate economic growth and residential opportunities along the proposed corridor. But the incestuous business and political relationships of the Republican Organization, the predominant political machine in Philadelphia, undermined the integrity of the venture from its onset.

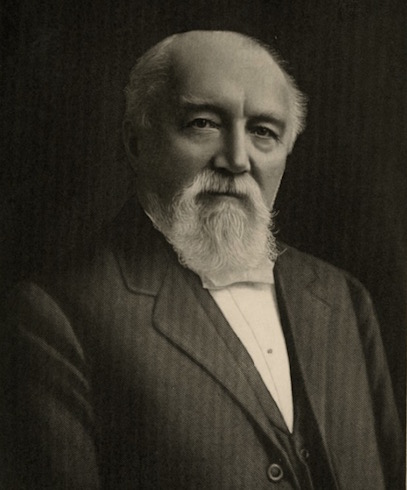

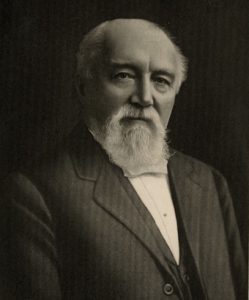

Engaging in the sordid practice of “honest graft,” the Philadelphia Land Company, which was established in 1902 by well-connected and corrupt Organization officials, purchased land extending from downtown Philadelphia to Torresdale through which the modern thoroughfare would be constructed, even though it served no immediate, practical purpose, largely because few inhabitants of the area lived close to the proposed roadway. Because of its close political ties with city officials, the Philadelphia Land Company eventually sold the properties it had acquired from local farmers to the City of Philadelphia for a generous return on its initial investment. Future mayor Rudolph Blankenburg (1843-1918), a highly respected businessmen and civic reformer, criticized the crass nature in which the Boulevard scheme had been conceived, for he deemed it the “culmination of Organization effrontery and thievery. . . which is open to curves as crooked as its projectors.”

Designated the “Torresdale Boulevard” at its inception–largely because Torresdale would serve as the roadway’s northeast terminus–the road developed in phases between 1903 and 1914. To forge the much sought-after link between downtown Philadelphia and Torresdale, home to many affluent families who might be enticed to patronize the department stores of downtown Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Department of Streets established a right-of-way from Broad and Cayuga Streets to the Boulevard, which was renamed the Northeast Boulevard—principally because it did not officially extend to Torresdale upon its initial development—by the time of its official opening in 1914. Over the next four years, real estate interests drove the continued expansion of the boulevard toward Pennypack Creek, largely because they sought to capitalize on the burgeoning, and potentially lucrative, housing market in the lower Northeast. The Boulevard underwent one final name change upon the completion of its extension to the Pennypack Creek—making the roadway seven miles long—in 1918, when its principal supporters renamed it the Roosevelt Boulevard, in honor of President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919).

1920s: The Boulevard Flourishes

As federal and state transportation agencies became more involved in the construction of new highways prior to the Second World War, the City of Philadelphia gradually relinquished control of the Boulevard to federal and state highway authorities. The Boulevard therefore slowly grew into part of the nation’s transportation infrastructure. With widespread ownership of automobiles and federal oversight of a nationalized highway system following the Federal Highway Act of 1921, the Boulevard and its surrounding environment flourished in the 1920s with the construction of new commercial facilities, such as the Sears-Roebuck department store and a mixture of row houses and single-family residences. Formally absorbed into the federal interstate highway system in 1926, the Boulevard became part of the newly created U.S. Route 1, a north-south interstate highway stretching from Maine to Florida. Although the Boulevard functioned as one of many vital arteries along U.S. 1, the federal government ceded control over its local, physical maintenance to the Philadelphia Department of Streets and then, in 1937, to the Pennsylvania Department of Highways (later renamed the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation or PennDOT), which became the primary vehicle for initiating construction projects and obtaining funds from the federal government to finance them.

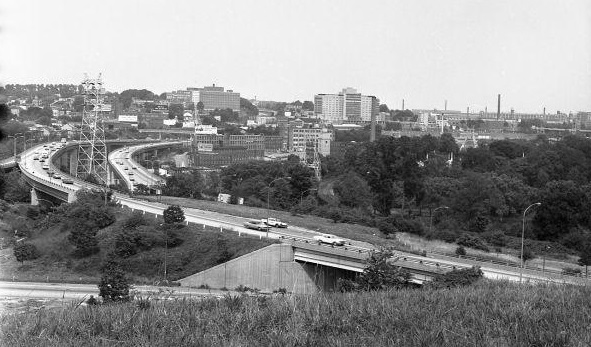

Following World War II, the City Planning Commission crafted highway policies in collaboration with state authorities that sought to remedy traffic issues and address residential concerns associated with postwar suburbanization and the entrenchment of an automobile culture. In 1947, the City Planning Commission, acknowledging the effects of the automobile on residential decentralization of the surrounding region, announced its plan to build the Roosevelt Expressway to bridge the physical divide between the existing Roosevelt Boulevard and the planned Schuylkill Expressway. Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), chairman of the Planning Commission, acted as an intermediary between aggrieved residents and state highway authorities over plans to construct the Boulevard Extension through densely populated neighborhoods. In 1950, Bacon met stiff resistance from Germantown residents who loathed the extension proposal and lobbied for the construction of a bypass north of the city to keep their neighborhoods free from the possible overflow of traffic congestion on the Boulevard. Bacon, however, disagreed with critics of the Planning Commission’s highway program, remarking that the bypass would only exacerbate, not alleviate, traffic problems inside city neighborhoods.

Although Bacon rejected the residents’ overtures for a bypass to divert traffic around their neighborhood, he nevertheless worked behind the scenes to secure support from the Pennsylvania Department of Highways to minimize the impact of the extension construction on local residents. He convinced the Department of Highways to narrow the lanes on the proposed extension from six to four, which kept 500 residents from being displaced. The eventual completion of the 3.5-mile Roosevelt Expressway in 1961, however, did little to ease traffic issues on the Boulevard, eventually compelling the commission to adopt another plan to relieve traffic snarls among the rapidly growing neighborhoods and thoroughfares of Northeast Philadelphia.

Northeast Expressway Proposal

The alternative remedy to the traffic quagmires on the Boulevard–a proposed Northeast Expressway devised by the City Planning Commission in 1964–met relentless attacks from state officials and Northeast residents. While the Boulevard had been expanded into the Far Northeast to accommodate residential expansion and shopping centers in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Northeast Expressway proposal would have extended 14.9 miles from Hunting Park in North Philadelphia to Bensalem in Bucks County. An accompanying nine-mile extension of the Broad Street Subway Line also would have expanded public transit options for those living in the Northeast. PennDOT purchased homes along the Boulevard during the early 1970s to make way for the expressway, but many residents and activists in the Near Northeast objected, arguing the extension would disrupt residential life and pollute Tacony Creek Park. PennDOT and Philadelphia city officials scrapped the expressway proposal in the early 1980s, daunted by the economic, political, and social hurdles they would have to overcome.

After the demise of the Northeast Expressway proposal, city and state officials attempted repeatedly to improve the quality of transportation and safety along the Roosevelt Boulevard. Attempting to resolve structural problems plaguing the twelve-lane boulevard, in 2003 the City Planning Commission completed the Roosevelt Boulevard Corridor Transportation Investment Study, which explored ways to improve the grading and routing of the Boulevard and called for mass transit alternatives to alleviate traffic. In 2008, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s Long-Range Vision for Transit modified some of the ideas in the 2003 study, envisioning, for instance, an extension of the Broad Street Subway and an elevated line along the Boulevard to the Bucks County boundary. Far from a settled issue, the ongoing policy debates about the Boulevard’s development remained not only an outstanding question among city planners and state officials but also reflected the complex, political forces that brought it into existence over a century ago.

Matthew Smalarz is a Ph.D candidate at the University of Rochester who teaches history at Manor College. His dissertation examines middle-class whiteness and public space in Northeast Philadelphia following World War II. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Speed cameras may go up on deadly Roosevelt Boulevard (WHYY, April 21, 2014)

- House Committee hears emotional testimony in favor of speed cameras on Roosevelt Boulevard (WHYY, September 19, 2016)

- SEPTA proposes new buses for University City, Roosevelt Blvd. (WHYY, February 15, 2017)

- Philadelphia's deadliest road inching toward speed cameras (PlanPhilly via WHYY, March 15, 2019)

Links

- Roosevelt Boulevard Transportation Investment Study (PDF, 2003)

- The Roosevelt Boulevard Subway Is Dead ... Unless It Isn't (Philadelphia Magazine)

- From Above: Roosevelt Boulevard, Oxford Circle, and Beyond in 1927 (PlanPhilly)

- "The Boulevard" (PhillyHistory.org)

- Roosevelt Boulevard: The Deadliest Road in Philly (WHYY Radio Times)