Reading Terminal Market

By Matthew Smalarz | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Opened to the public in 1893, Reading Terminal Market came into being amid the chaotic, but transformative, industrial and commercial forces that swept through late nineteenth-century Philadelphia. A descendant of the market-oriented atmosphere and culture entrenched primarily along High (subsequently Market) Street since the colonial era, the Reading Terminal weathered myriad commercial, labor, and legal hurdles during its storied evolution, standing apart as a marketplace innovator that overcame structural and competitive challenges that repeatedly threatened its continued development.

Rooted in the long tradition of market venues scattered throughout the city that pedaled and sold various farm goods and meats, the origins of the Reading Terminal Market stemmed from a change in state law in the early 1850s conferring new economic powers on private market houses. Responding to the poor condition and fiscal mismanagement of the aging and decrepit market sheds that had long dotted the congested corridor of High Street, the city ordered them to close in October 1859. To replace them, the proprietors of private market halls invested considerable capital to attract customers by constructing ornately designed, well-ventilated, and refrigerated facilities. By the advent of the Centennial celebration in 1876, guidebooks could tout a vast array of market house options throughout the city’s neighborhoods.

Two private markets houses—The Farmers’ Market and the Twelfth Street Market—exemplified the push to erect appealing facilities, but their success was threatened by the intense rivalry between the Reading and Pennsylvania railroads in the 1880s and early 1890s. Feeling the pressure to expand its operations to counter the Pennsylvania Railroad’s recent construction of a new railroad shed—Broad Street Station—at Broad and Filbert, the Reading lobbied City Council to build a new train terminal at Twelfth and Market Streets, threatening in the process to displace the two markets through eminent domain. To compete with its rival in the heart of downtown, the Reading also aimed to erect a marketplace venue that would attract more customers to utilize its passenger lines. Unwilling to allow the Reading Railroad to determine their fates, however, representatives from both markets lobbied the Reading throughout the summer of 1891, finally brokering a deal that granted them commercial space on the ground level of Market Street, immediately beneath the rail line’s proposed elevated track and terminal. There, they could expect to operate their stalls, as well as to maintain access to a newly constructed cold storage basement in which to store perishable foodstuffs.

To elevate the physical grandeur of the proposed market, the Reading Railroad contracted the services of George McKay, who had built the resplendent Center Market in Washington, D.C., to monitor the construction of its grandiose terminal facility, while consulting with Francis Kimball (1845-1919), a New York-based architect, to devise the ornamental features that would grace its structural façade. The train shed alone was estimated at 559 feet in length and 88 feet in height and sheltering thirteen train tracks, on which thirteen load-bearing locomotives and an endless array of train cars could be placed. The terminal’s architectural features, which included 135,000 feet of glass and 50 million pounds of iron, soon marked it as one of the finest market venues in the nation. The market officially debuted February 22, 1892, even as ongoing construction forced multiple delays, such as a leaky, makeshift roof and the installation of the cold storage unit. Upon completion in January 1893, the market was almost entirely occupied by vendors of all types, selling a wide array of seafood, meat, produce, and poultry items, while its outstanding architectural and engineering flaws had been fully resolved.

Reading Railroad Bankruptcy

The Reading Railroad, however, after falling into financial disrepair as part of a devastating national depression, declared bankruptcy in 1893. To salvage the railroad from further financial ruin, the Philadelphia and Reading Railway Company, which obtained the lease to the Reading Terminal, converted its assets into a holding company after consulting with J. Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), the most influential financier of the Gilded Age.

The market weathered a series of maintenance challenges upon its opening, the most notable being the replacement of the recently installed roof from 1897 with a sturdier and less porous one in 1901. Despite this, the market prospered into the mid-twentieth century because of its wholesale supply operations with local dining establishments, its ability to ship goods across the country through the U.S. Express Parcel Company—a shipping entity under the direction of the Reading Company—and the importance of its cold storage unit. In the first decade of the market’s existence, 380 vendors established their presence by selling a wide variety of foodstuffs, most notably fish, poultry, various meats, flour, tea, coffee, spices, and ice cream. Bassett’s Ice Cream, which occupied a room in the upstairs of the market beginning in 1898, became a notable fixture in the market by creating ice cream at its own stand.

The emergence of supermarket chains, with the capacity to sell a wider variety of foodstuffs, threatened the stability of the market during the early twentieth century. The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company debuted its “economy stores” starting in 1912, and soon thereafter opened a store on Twelfth Street directly across from the Reading market to compete for its customers.

Challenges of the 1950s

The Reading Railroad and its market merchants also dealt with a multitude of structural and financial hardships following World War II, as the rise of an automobile culture, changing consumer trends, and marketplace competition affected their industries. Despite efforts to refurbish its facilities in order to attract more passengers and alleviate labor tensions among its rank and file, the Reading Railroad was forced to downsize by closing numerous stations and unloading unprofitable property holdings by the late 1950s. The economic decline of the railroad affected, and coincided with, the falling revenues and occupancy rates of the market during the 1950s, which increasingly struggled to retain merchants and attract customers.

Faced with these mounting obstacles, the Merchants’ Association of the Reading Terminal Market in 1958 petitioned the rail company to provide security through long-term leases, but quickly shelved the plan when disagreements arose among its members over the proposal’s financial viability. Instead, the Reading raised rental fees on its merchants to offset its financial losses and entertained offers from real estate developers to convert the market into a “Merchandise Mart,” which would sell discounted goods to improve the financial standing of its merchants. The company also considered an offer from the city to transform the market into a bus station and parking garage at a time when major planning initiatives, including the proposed construction of the Vine Street Expressway and Market East, aimed at drawing in affluent, white suburbanites to patronize the Central Business District. The physical redevelopment of Society Hill momentarily increased market patronage, but the ongoing decline of tenants, which rested at 70 percent occupancy in 1959, only dampened hopes that it could withstand the financial challenges besieging it.

The Reading Company, which declared bankruptcy in 1971, further distanced itself from the financial calamities that plagued the market by selling a third of its shares to Chicago real estate investors and then proceeded to hand control of train operations over to Conrail and SEPTA. The railroad also sold the property on which the market stood to free itself from further financial entanglements, reaching a five-year lease agreement in 1976 with Sam Rappaport (1932-2016), a prominent real estate mogul who hoped to profit from his investment by transforming the market into a festival marketplace akin to the recently refurbished Faneuil Hall in Boston to coincide with the city’s Bicentennial celebrations. Challenging Rappaport’s plan to compel them to sign long-term leases on individual terms rather than traditional, monthly leases, its remaining merchants, especially the outspoken butcher Harry Ochs (1929-2009) rallied to force Rappaport to acquiesce to their demand for short-term agreements. To further appease the merchants, the Reading Company negotiated a deal whereby it acquired his remaining financial holdings in the market in the late 1970s.

1980s Revitalization

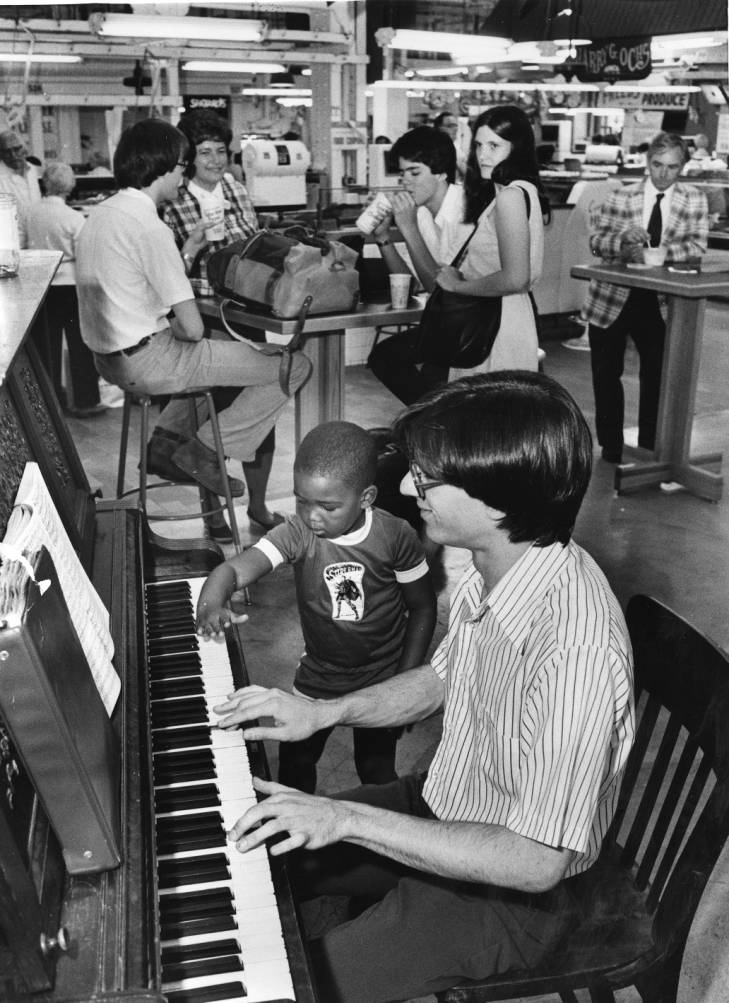

The ambitious push to revitalize the market and its surrounding neighborhoods in Center City compelled Reading to develop and invest in new real estate projects, the most notable being the construction in the early 1980s of a thirty-two-story office structure and an immense parking garage aimed at catering to market patrons. To demonstrate its commitment to the revitalization of the market, the company also planned to shift its real estate operation back to the terminal to bolster its property assets. The diversification and addition of new vendors, notably Amish farmers and Asian produce vendors, also widened the variety of food offerings. It became the embodiment of what ethnologist Elijah Anderson has called a “cosmopolitan canopy”—a social space where diverse peoples come together, and for the most part practice getting along—amid its resurgence during the 1980s.

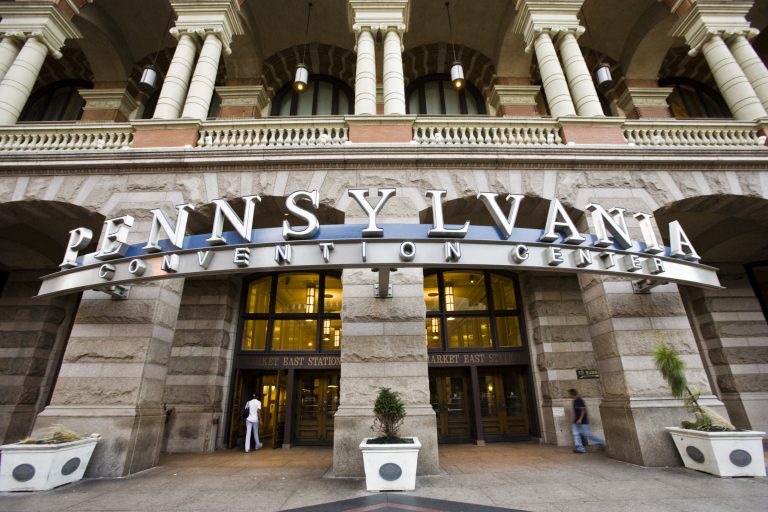

Concerned merchants, however, worried that plans to redevelop the area around the market with an immense, new convention center would threaten its existence under the direction of a new state entity—the Convention Center Authority. Fearful about the possible implications of the state’s assumption of the convention project on the market, Robert Brecht and Harry G. Ochs Jr. (1929-2009), two of the market’s most visible tenants, revived the Merchants’ Association—which at various points throughout the history of the market had represented the legal and negotiating needs of market tenants—in order to launch a petition campaign to keep it from closing. They obtained over seventy thousand signatures in support of their campaign to modify the convention center proposal in order to keep the market open. Heeding the voices of frustrated merchants and customers, city politicians and leaders organized a blue-ribbon panel to protect the physical appearance of the market. Immediately prior to assuming full control of the project in late 1990, the Convention Center Authority reached an accord with merchants in which it not only promised to keep the market operational during the construction project, but also to reimburse them for any structural damages incurred and preserve important historical trappings of the market, specifically merchant counters and stalls.

Having endured countless economic trials, structural hurdles, and legal obstacles throughout its storied past, the revitalization of the market enabled it to thrive well into the twenty-first century. Fresh produce and a vast array of food offerings—Thai, Indian, Cajun, Pennsylvania Dutch, and other cuisines from around the nation and the world—drew consumers from various backgrounds into one of the most distinctive cultural, social, and culinary experiences in modern Philadelphia.

Matthew Smalarz teaches history at Manor College in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, where he serves as Chair of the Social Sciences Department and received the Outstanding Educator of the Year Award for the 2016-17 academic year. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University