Children’s Theater

Essay

In Philadelphia, the theater capital of the United States until New York overtook it in the 1830s, an array of children’s theater activity has long sparked creativity and imagination, informed, and educated young people with live performances. Early staged productions for the entire family increasingly gave way to child-specific theater combining education with entertainment. In the twentieth century, the children’s theater company grew to include commercial and non–commercial professional productions, non–professional community groups, and educational theater companies.

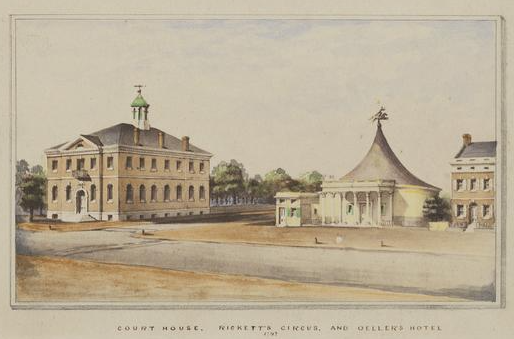

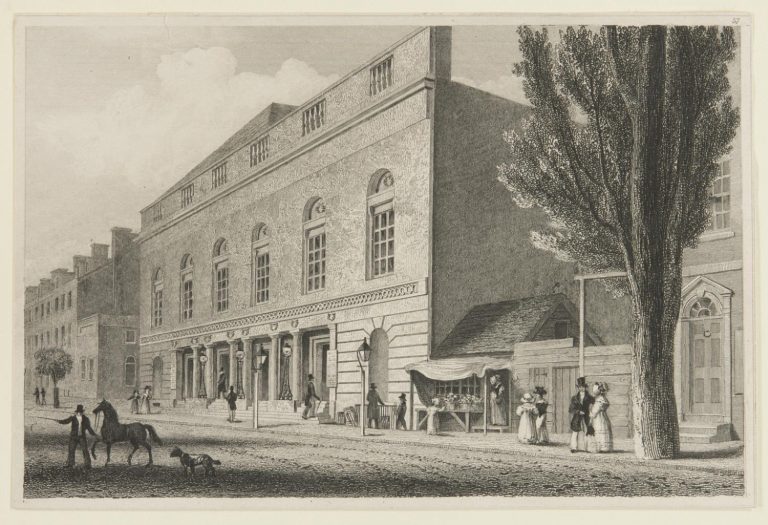

Throughout the eighteenth and into the late nineteenth century, theatrical entertainment was generally not segmented by age. Rather than “children’s productions” or “adult productions” theater producers assumed attendance by a general audience that included children with their parents or working youths who could afford the price of admission. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, an evening’s dramatic entertainment often included pantomimes (pantos), usually based on fairy or folk tales with strong comic elements. The pantomime Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper by Michael Kelly (1762-1826), first performed in 1804 at London’s Theatre Royal, debuted at the Chestnut Street Theater in 1806 to great success. In addition to legitimate stage productions such as those at the Walnut and Chestnut Street Theaters, Philadelphia’s children and youths attended the first American circus, founded in 1793 at Twelfth and Market Streets by the Scottish circus impresario John Bill Ricketts (1769–1800). Later generations of children and working youth attended vaudeville and minstrel shows at venues such as the Arch Street Opera House (founded in 1870 and later renamed the Trocadero Theater) and spectacles including Philadelphia’s Cyclorama (1888-90), which presented spectacular –360– degree paintings such as The Battle of Gettysburg and Jerusalem on the Day of the Crucifixion in a circular-shaped building at Broad and Cherry Streets.

While children remained part of a general audience for amusements the city offered, in the late nineteenth century child-specific theater arose in response to the emerging concept of a “protected childhood.” This era of a rising middle class, urbanization, and shifting cultural values produced specialized child-related material culture such as furnishings, clothing, literature, and entertainment. Theaters advertised offerings specifically for children or matinees adapted and advertised as “suitable for ladies and children.” For example, in 1891 the Grand Opera House (Broad Street and Montgomery Avenue) produced Gulliver’s Travels with the Lilliputians played by the “Royal Midgets.” In 1893 the Walnut Street Theater offered a matinee performance of “Terry’s Funny Pantomime,” and in 1895 a “specially adapted” matinee vaudeville performance took place at Mathews and Bulger’s Company at The Auditorium (Eighth and Walnut Streets).

Encouraging Creativity

Educational theater emerged during the Progressive Era (c. 1890-1920) of social and political reform as teachers, social workers, and other child advocates viewed live theater as a venue for introducing language skills, encouraging creativity, and teaching positive values to the growing number of immigrant children in America’s cities. The City of Philadelphia created play spaces for children and youth as well as opportunities for adult-led leisure activities such as sports, arts, and crafts. By the early 1930s, Philadelphia’s fifteen recreation centers offered a robust dramatic program for children and youth with a reported 1,100 participants. While the Recreation Department’s productions featured child actors participating in a volunteer activity, the Junior League of America also brought theater to Philadelphia’s children in the form of professionally produced plays with adult actors and the goal of promoting literacy and academic achievement. The Children’s Theater, sponsored by the Junior League of Philadelphia beginning in 1927, continued to serve school children in the twenty-first century. The Women’s International League and the Philadelphia Art Alliance also sponsored professional productions such as those by the Clara Tree Major players for area children at theaters across Philadelphia from the 1920s into the 1950s.

By the latter part of the twentieth century Philadelphia’s children’s theater community became increasingly interactive and participatory, create a new role for child audiences. In the late 1960s the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts sponsored several successful children’s theater initiatives, including the Society Hill Playhouse’s Philadelphia Youth Theater (1970–83); Society Hill’s Street Theater (1968–70), in which young adult and adult actors traveled to Philadelphia neighborhoods with live productions; and the Free Children’s Theater of the Germantown Theater Guild, which offered free children’s programming throughout the 1970s.

The Children’s Repertory Theater, founded by Dr. Hans Walter Wenkaert (1909–80) and active during the 1960s and 1970s, demonstrated collaboration between adults and children. Featuring a company of child actors who performed for a child audience, the company originally was located at 1617 Locust Street home of the Philadelphia Musical Academy. Wenkaert, who immigrated to the United States from Germany before World War II, brought to his work the European tradition of regarding children’s theater as a venue for encouraging agency, identity, and creativity. The company produced shows based on fairy tales and children’s literature such as Puss in Boots and Peter Pan.

Child Empowerment

The political climate of the 1960s and 1970s shaped educational theater with progressive themes of child empowerment, tolerance, and acceptance. The Philadelphia Youth Theater under the direction of Susan Turlish (b. 1946) produced versions of A Clockwork Orange and Animal Farm. Laurie Wagman (b. 1932) founded American Theater Arts for Youth in 1971 with the goal of educating and entertaining children through theater arts, particularly children who may not have had access to live theater previously. Performances, based on children’s classics and historical figures, featured high production values and Equity actors. They included Black Journey, an original musical that surveyed three hundred 300 years of African American history. Based in Philadelphia, this organization garnered a national reputation for bringing live theater productions to children for over forty years.

As the baby boom of children born 1946-60 produced an expanded youth audience, children’s shows became a staple of the summer tent music venues such as the Valley Forge Music Fair (active 1954–96), the Camden County Music Fair (active 1956-69 and 1972-73), the Lambertville Music Circus (1949–69), and the Playhouse in the Park in Fairmount Park (1952–79). Performance spaces that hosted children’s shows also included the Electric Factory Children’s Theater at 2201 Arch Street, the Karenga Cultural Arts House at 1711 N. Croskey Street, and the Society Hill Playhouse. University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts became home to the annual Philadelphia International Children’s Festival of performing arts in 1975.

By the twenty-first century, children were encouraged to be not only participants but also writers and artists. The children’s theater community consisted of commercial and non-commercial ventures including professional productions (those employing Actor’s Equity members), non–professional community groups, and educational theater companies. Children’s series and acting programs continued in Philadelphia at the Walnut Street Theater, the Arden Theater, and the MacGuffin Theater and Film Company (Twentieth and Sansom Streets); People’s Light in Malvern; and the Hedgerow Theater in Media. Philadelphia Young Playwrights (1219 Vine Street) worked with elementary and high school-aged children and to encourage creative writing skills and an interest in the lively arts through its classes and, beginning in 1987, an annual Playwriting Festival.

As the concept of “child audience” evolved in popular culture from the early the nineteenth century to the present, so did productions in children’s theater. In addition to attending adult-created and produced plays, children and youth in Philadelphia gained a hand in writing and directing their own content. By engaging the next generation of thespians, Philadelphia’s theater community continued a centuries-long history of live stage productions for child audiences.

Vibiana Bowman Cvetkovic is a Librarian Emerita of the Rutgers Universities Libraries and an adjunct professor of English at Atlantic Cape Community College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University