Airports

By Demian Larry

Essay

Commercial aviation grew dramatically in the United States in the twentieth century, and a number of airports in the Philadelphia area grew to become regional centers of the industry. There was nothing assured or inevitable about this growth, however. It depended on the efforts of local political leaders, investments by the aviation companies, and state and federal aid.

Parks and racetracks served as the first landing areas for airplanes in Philadelphia, but by the late 1920s designated airfields dotted the city and surrounding region. While most were privately owned, the federal government established a flying field at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and a seaplane base on the Delaware River in Essington, Pennsylvania. Just upstream from Essington in the Eastwick section of southwest Philadelphia, the city built its first municipal airport in 1926 to serve as a site of operations for a Pennsylvania National Guard squadron, a commercial flying service called the Ludington Exhibition Company, and the U.S. Post Office’s new airmail flights between Washington, D.C., and New York City.

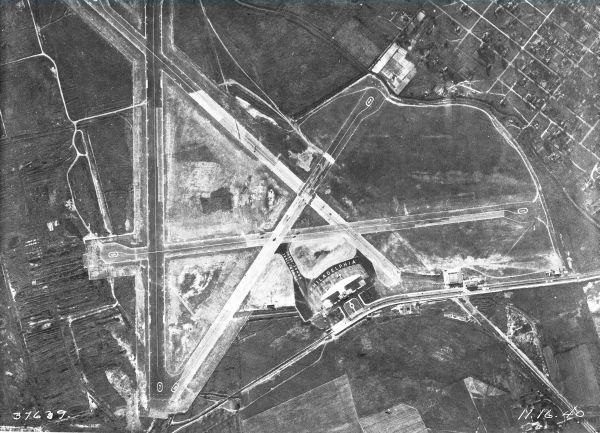

While the Eastwick field was soon deemed inadequate for Philadelphia’s needs, constructing a larger city-owned and -operated airport proved difficult. Work began in 1931 on an expanded tract, which included the Eastwick property and land on adjacent Hog Island purchased from the federal government, but this project ground to a halt the next year, a victim of the Depression and a fiscally conservative mayor, J. Hampton Moore (1864-1950), who cut the city’s public works budget. Most flying activity, including the airmail service, had already shifted across the Delaware River to the less flood-prone Central Airport on Crescent Boulevard in Pennsauken, New Jersey, and construction languished until 1936 when a new mayor, S. Davis Wilson (1881-1939), restarted the work with funds made available under the New Deal. Although a laborer strike and a dispute between the city and the federal government over the location of a runway delayed completion, the new Philadelphia Municipal Airport officially opened in 1940.

When the United States entered World War II, military operations at area airports increased. Philadelphia Municipal Airport and the Greater Wilmington Airport in New Castle County, Delaware, served as Army Air Corps bases, and Mercer Airport near Trenton functioned as a test site for Navy planes built at a nearby plant. The government also purchased a few privately owned airfields during the war. One in Northeast Philadelphia was improved and donated to the city in 1944, while another in Montgomery County, Willow Grove Naval Air Station, would remain an active military facility for decades after the war.

Postwar Aviation Boom

With the war’s end, commercial aviation in the United States boomed, and the City of Philadelphia worked to make its municipal airport a part of the growing industry. It renamed the facility Philadelphia International and turned to the federal government for money to help build longer runways and a larger terminal. Before 1946, the U.S. government funded municipal airport development on an ad hoc basis, via New Deal work relief programs and wartime national defense projects. In 1946, though, Congress established a grant program to subsidize construction and renovation and thereby promote a national network of airports. Federal grants became a continuous source of funding for airport construction from the late 1940s into the twenty-first century and helped fund a new international airport on Hog Island that opened in December 1953.

In the 1950s, Philadelphia International gained more flights to other cities in the United States and abroad. City leaders also campaigned to terminate the leases of the National Guard and air force reserve squadrons based at the international airport, believing they impeded commercial flying operations. Military leaders offered to pay for an expansion of the Northeast Philadelphia Airport if their units could operate there, but the city rejected the idea and the units eventually relocated to Willow Grove Naval Air Station in the early 1960s. The Mercer County and New Castle County fields served less controversially as homes to National Guard squadrons in the decades after World War II and, along with the Northeast Philadelphia Airport, supported business aviation, charter and recreational flying, and light manufacturing.

By the mid-1960s, traffic at Philadelphia International had reached record levels, and officials decided it would have to be expanded to accommodate future growth. With financial support from the state and federal governments, the city began construction of new runways, terminals, parking lots, and a SEPTA regional rail line connecting the airport to Center City. While the investments were welcome, their management drew heavy criticism in the 1970s because of delays, cost overruns, and revelations that city and political party officials had accepted bribes from construction firms bidding on contracts. Some critics called on Philadelphia to cede its control of the airport to an independent authority that they said would manage it impartially and in the best interests of the whole metropolitan region, but city leaders successfully resisted the idea.

When Congress voted in 1978 to deregulate the airline industry by abolishing the Civil Aeronautics Board, the airline business and the business of airport management both changed. For forty years, the CAB had dictated who could start an airline, what cities it could serve, and what fares it could charge. After 1978, market competition answered these questions and cities assumed more direct responsibility for attracting airlines to their airports. Greater competition encouraged airlines to establish hubs—specific airports where they concentrated their operations— and cities competed for hub status to gain more flights, jobs, and revenues. Deregulation also allowed low-cost carriers to proliferate. These airlines usually provided fewer amenities and routes but offered travelers lower fares and helped offset the inflationary effect a larger carrier operating a hub at the same airport tended to have on ticket prices.

Hub for US Airways and UPS

While the 1980s and 1990s were a volatile time for the industry as airlines grappled with the realities of deregulation and many new and long-established carriers went out of business, traffic at Philadelphia International generally increased. The airport became a hub for US Airways and United Parcel Service, attracted service from a number of low-cost carriers, and saw new facilities develop to handle growing airplane, passenger, and automobile traffic. This expansion sparked conflicts with neighboring communities like Delaware County’s Tinicum Township, in which much of the airport lay, over property tax payments and plane noise.

In the early twenty-first century, discount airlines began flying from some of Greater Philadelphia’s smaller regional airports. With reduced operating costs and less tenant demand, the fields charged airlines lower rents and landing fees, making them compatible with the budget airline business model, and the airports’ locations along limited-access freeways made them accessible to area travelers. The Atlantic City, Mercer County (now Trenton-Mercer), and New Castle County (now Wilmington-Philadelphia) airports all gained new service from discount airlines in this period.

Global demand for private jets and civilian helicopters grew after 1980, and a number of aircraft companies established assembly and maintenance facilities at area airports during that time. AgustaWestland, an Italian-British helicopter builder, opened a shop at Northeast Philadelphia Airport in 1982 that later expanded into a manufacturing facility; Dassault Aviation of France established a maintenance, repair, and overhaul station for its business jets at Wilmington-Philadelphia Airport in 2000; and in 2007, American firm Sikorsky began assembling helicopters in a plant at the Chester County Airport in Coatesville, Pennsylvania.

State and local governments helped entice these companies with tax breaks and construction financing. The fields also offered manufacturers less air traffic and lower rents than large commercial airports; proximity to deep-water ports, interstate highways, and railroads; and an established supply chain and skilled labor pool, thanks to Boeing’s long-time presence as a helicopter builder in Ridley Park, Pennsylvania.

By the early twenty-first century, many of Greater Philadelphia’s airports were regional centers of the world’s commercial aviation industries. While globalization led to the loss of traditional industrial jobs in the area, it fostered new employment, including manufacturing and mechanical jobs, at the airports. The growth of the local aviation economy was not an inevitable consequence of globalization, however. Intentional policies of development and investment, both public and private, made it possible.

Demian Larry is a Ph.D. candidate in American history at Temple University. His dissertation is about the politics and economics of airport development in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- A.C. Airport has built it... hoping international travelers will come (WHYY, November 26, 2012)

- Delaware airport's runway expansion finally takes off (WHYY, August 17, 2012)

- Frontier Airlines shows off accommodations at Delaware airport (WHYY, June 26, 2013)

- PHL airport expansion to include extended runway, longer routes (WHYY, March 24, 2015)

- New Philly airport expansion plan spares Tinicum residences (WHYY, May 6, 2014)

- PHL getting spruced up for pope, DNC (WHYY, April 28, 2015)

- Last flight for US Airways expected in October; final destination Philadelphia (WHYY, July 11, 2015)

- Final US Airways flight, lands in Philly; included NC stop (WHYY, October 17, 2015)

- Atlantic City will put Bader Field up for auction (WHYY, March 17, 2016)

- Trenton-Mercer airport expansion plans worry neighbors in Pa. and N.J. (WHYY, July 29, 2018)