Bootlegging

Essay

Bootleg liquor, produced illegally during the Prohibition (1920-33), flowed into the Philadelphia region from a variety of sources, including overseas shipments, small home stills, large stills in urban factories and country barns, beer breweries, and manufacturers of industrial alcohol. Philadelphia’s location at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, just inland from the Atlantic Ocean, enabled deliveries of alcohol on ships from Canada, Europe, and the Caribbean. Trucks hauled imported liquor from coastal New Jersey towns like Atlantic City inland to Camden and Philadelphia, while beer arrived on trains from rural locales like Berks County.

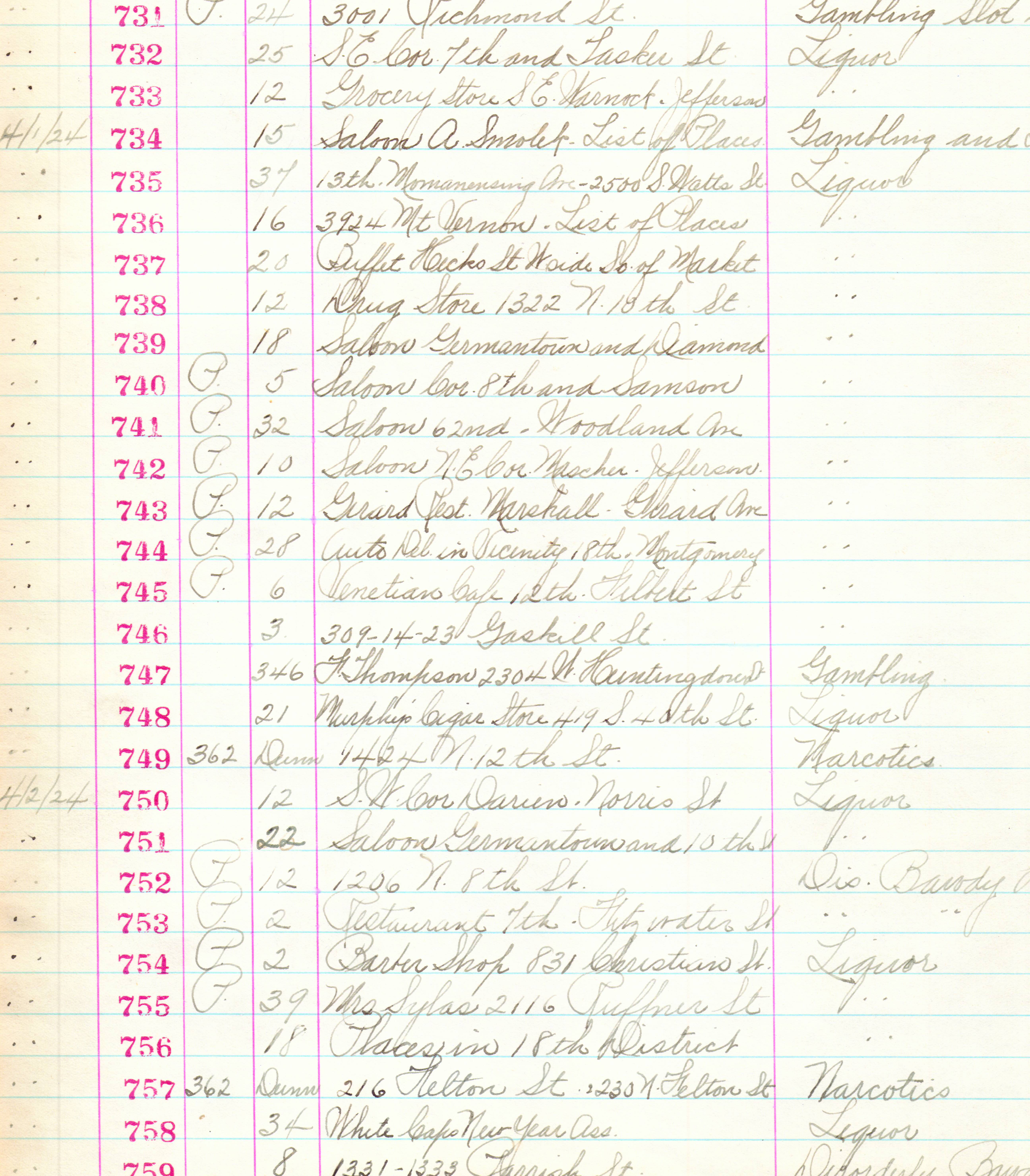

Bootlegging gained protected status in a region where neighborhood saloons often served as informal offices for local ward bosses. Corrupt politicians, many operating within the Republican machine, worked in concert with police captains to protect vice industries like prostitution and bootlegging. Police heads often received kickbacks from both their underlings—for job protection—and from the illegal entities in their district—for ignoring their illicit operations.

Just before Prohibition took effect, Philadelphia was home to 1,700 saloons. Nearly a decade later, investigators estimated that nearly 1,200 saloons still operated more or less openly. Philadelphians abided a city of speakeasies, patronizing the candy stores, barber shops, pool halls, and private residences that served illegal liquor. The multitude of breweries in Philadelphia, which had an extensive and centuries-old history of beer production, also continued to supply the region.

Risks of Bootleg Liquor

While police guessed that 8,000 unlicensed taverns operated throughout the city, journalists estimated that at least 8,000 more “blind tigers” sold intoxicants to Philadelphians. Imbibing bootleg liquor carried risk; over the course of one month in 1923, Philadelphia reported 307 alcohol-poisoning deaths to the federal Prohibition Bureau. Government chemists noted that most of their confiscated bootleg liquor samples contained wood alcohol, chloride, sulfuric acid, iodine, or some other poison. By the late 1920s, temperance forces in the government ramped up their anti-liquor crusade by introducing a formula that doubled the poison in denatured industrial alcohol. Imbibing a product redistilled improperly by amateur moonshiners, consumers ran the risk of blindness and death. Nonetheless, forty million dollars poured through Philadelphia’s liquor trade annually.

The Delaware Valley, a hub of the chemical industry, produced millions of gallons of industrial alcohol. Those holding federal permits to manufacture perfumes, medicines, and barber supplies received about 430,000 gallons of alcohol every month. Many of these permit-holders operated “coverup houses” that distributed alcohol to consumers. Investigators unearthed records detailing implausibly large deliveries of hair tonics and perfumes throughout the Philadelphia region, including a delivery of 500 gallons of “hair oil” to an unidentified town of just fifty people. From 1924 to 1928, the number of gallons of industrial alcohol released in Philadelphia doubled, from five million to ten million.

As Philadelphia’s industrial alcohol purveyors moved their product over land, high-profile rum-runners like Bill McCoy (1877-1948) set up shop in the Quaker City, moving their liquor into the city via its waterways. Bootleg liquor bound for Philadelphia often ran first through Atlantic City, described as a “smugglers’ paradise” because of the cooperation among rum-runners, local politicians, and Coast Guard officials. Rum-runners ushered as many as ten million quarts of liquor per year through the Bahamas and up the Atlantic Coast. McCoy and others sailed “Rum Row,” an Atlantic Ocean corridor stretching from Atlantic City to New York’s Long Island, making sure to stay outside of U.S. maritime limits (or working with corrupt Coast Guard officers) as they brought bootleg shipments northward. Though the term “the real McCoy” emerged in an earlier era, it was used by McCoy’s biographer in 1931 to signal the bootlegger’s unadulterated product: high-quality, single-source imported liquor.

The Regional Network

Numerous bootlegging gangs serviced the city alongside Philadelphia’s bootlegging kings, Max “Boo Boo” Hoff (liquor) (1895-1941) and Mickey Duffy (beer) (1888-1931). Philadelphia bootleggers worked in concert with South Jersey syndicates, who in turn partnered with North Jersey and New York City operatives. Max Hassel (1900-33), a bootlegger from Reading, Pennsylvania, who owned more than a dozen breweries in Pennsylvania, New York State, and New Jersey, paired with Duffy to operate several beer breweries in South Jersey, including Camden County Breweries Inc. and Camden County Cereal Beverage Company. Hassel also worked with Irving Wexler (1888-1952), commonly known as Waxey Gordon, a prominent bootlegger and associate of New York City crime kingpin Arnold Rothstein (1882-1928).

Philadelphia’s bootleg trade depended on the region’s roads, rail routes, and waterways—its interconnectivity and proximity to other import and export hubs, like Trenton, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware. Bootleg business that affected Philadelphia often affected the surrounding region. When investigators probed bootleggers and racketeers in Philadelphia during the 1928 Special August Grand Jury investigation, some illicit entities crossed the Delaware River to Camden, New Jersey; as Philadelphia became more temperate, Camden became less so.

Charged with investigating bootlegging and its attendant gang violence, the 1928 Special August Grand Jury revealed the extent to which illegal liquor saturated the region, putting bootleggers on the defensive. The grand jury found that over the course of a few months, in excess of a million gallons of consumable liquor was released into the city, much of it diverted from denatured industrial alcohol. Philadelphia boxing promoter and nightclub owner Max Hoff built a bootlegging empire from industrial alcohol and amassed a fortune. Hoff operated several financial firms, including the Franklin Mortgage & Investment Co., to manage the revenue from his bootlegging ventures.

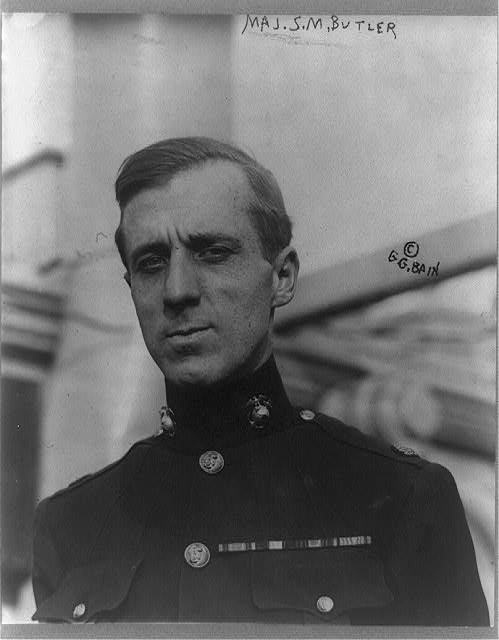

Despite interviewing 748 witnesses, the grand jury failed to indict Hoff or any other big-name bootlegger. Its success lay in uncovering police graft. When the grand jury finished its work, 138 police officers were deemed unfit for service. Many of these officers worked within Unit No. 1, an elite vice force established in 1924 by Director of Public Safety Smedley Butler (1881-1940).

In its report, the grand jury admitted it failed to destroy an underworld architecture built on bootlegging. In noting the lack of a permanent solution to the liquor racket problem, it implicated the residents of Philadelphia. It reasoned that only a constantly vigilant citizenry could prevent bootlegging, violence, and police graft. District Attorney John Monaghan (1870-1954), leading the investigation, implored Philadelphians to insist upon clean government and law and order. His exhortation echoed the voices of many Pennsylvania reformers of the 1920s, including Butler and Governor Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946). The will of Philadelphians to abide by Prohibition remained limited, however, and officials who zealously enforced the unpopular federal mandate assumed a hefty political liability. Bootlegging in Philadelphia continued until Prohibition’s repeal, meeting the unwavering demand for liquor.

Annie Anderson is the senior research and public programming specialist at Eastern State Penitentiary and the co-author, with John Binder, of Philadelphia Organized Crime in the 1920s and 1930s (Arcadia Publishing, 2014). She received her M.A. in American Studies from the University of Massachusetts Boston. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University