Burlesque

Essay

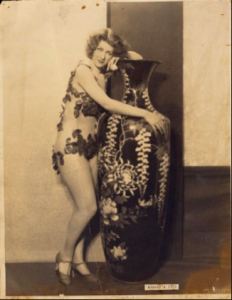

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Philadelphia became one of the central nodes of American burlesque, a genre with origins in the ribald Victorian “travesties”—theatrical parodies of well-known operas that relied upon risqué and absurd humor. Distinct from its English counterpart, American burlesque incorporated elements of minstrelsy and, especially by the end of the nineteenth century, striptease and vaudeville acts. The ebb and flow of burlesque’s popularity from its origins through the early twenty-first century reflected shifting sexual mores in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

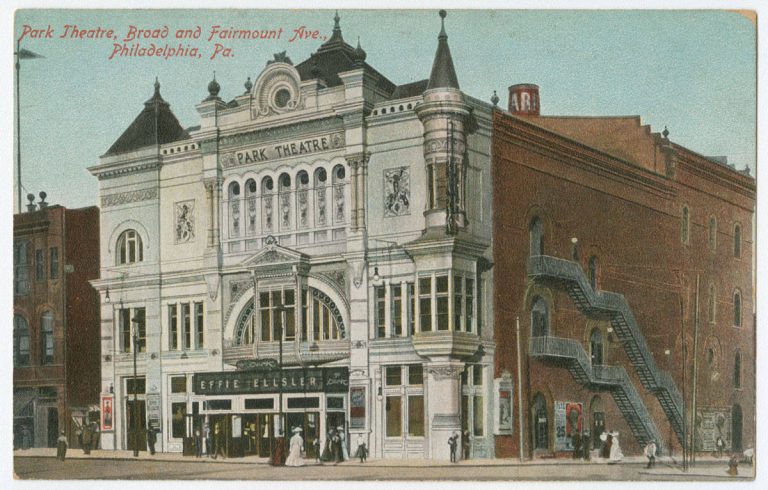

In contrast to vaudeville entertainments, burlesque shows thrived on crossing boundaries of social acceptability and liberated performers from traditional categories of race and gender, which became slippery and ambiguous. Philadelphia hosted perhaps a dozen burlesque theaters in the late nineteenth century, clustered primarily in the Center City district of commercial sex and vice industries known as the Tenderloin. The venues included Dumont’s Theater, the 11th Street Opera House, the Gayety, the Empire, the Nixon, the Keystone, the Liberty, the Grand, the Star, the William Penn Theatre, the Auditorium, and the Arch Street Opera House.

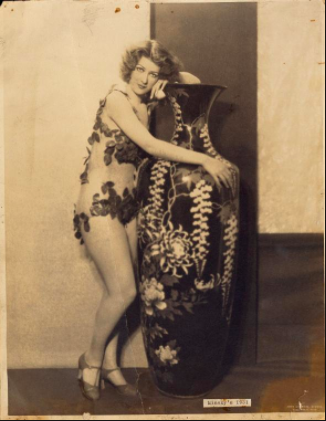

Established in 1870, the Arch Street Opera House—known in the twentieth century as the Casino Theatre, the Palace Theatre, the Troc Theatre, and the Trocadero Theatre—served as the hub of burlesque performances in Philadelphia throughout the first half of the twentieth century. In the heart of the Tenderloin at Tenth and Arch Streets, the Arch Street Opera House stood within walking distance of brothels, opium dens, saloons, and shooting galleries. Primarily a minstrelsy theater until the end of the nineteenth century, the Arch Street Opera House served as a significant appendage of a wider circuit of traveling burlesque performers into the mid-twentieth century, hosting such celebrated burlesque artists as Gypsy Rose Lee (1911-70) and Blaze Starr (1932-2015). In fact, it was in Philadelphia that Billy Minsky (1887-1932) of Minsky’s Burlesque in New York first saw Gypsy Rose Lee perform, leading him to offer her a position as the troupe’s headliner.

By the early twentieth century, the field of American burlesque had split into two main circuits: the Columbia Circuit and the Empire Circuit. While the former preferred to produce somewhat “cleaner” shows, the latter designed “their shows to be as smutty as they could convince local authorities to overlook.” By this time, Philadelphians could also see burlesque shows at the Lyceum Theatre on Vine Street, and the Bijou Theatre on North Eighth Street, formerly a vaudeville theater, introduced burlesque performances starting in 1910. By the 1920s, however, burlesque became increasingly professionalized and lost its subversive edge, with performers designing their performances to meet the interests of male producers and booking agents, who marketed burlesque primarily toward the voyeuristic pleasure of white male viewers, to the exclusion of mixed-gender audiences and viewers of color. For example, historian Robert C. Allen has noted that, with the rising popularity of the cooch dance—a kind of gyrating, highly sexualized dance—“the burlesque performer’s mouth became the only part of her body that did not move,” indicating the degree to which she had become “linguistically disempowered.” Progressive reformers also worked to clamp down on urban vice, and the Tenderloin district entered into a period of decline.

Burlesque lost much of its titillating appeal with American audiences as nudity became more common in cinema and live theater. In the words of cultural studies scholar Alan Trachtenberg, American burlesque reached “its final shabby demise” by the 1950s. Consequently, venues like the Bijou Theatre closed down. The Troc rebranded itself in the 1970s as an art house cinema and, by the end of the twentieth century, as a concert venue for rock music.

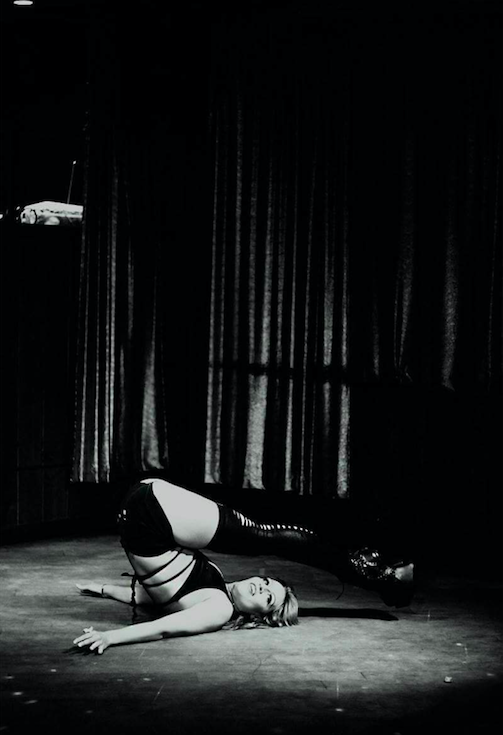

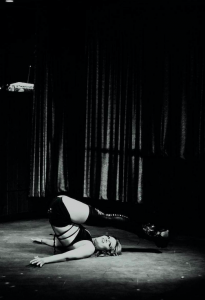

If burlesque’s midcentury demise was shabby, though, it was not final. In the 1990s, American burlesque experienced a revival. Dubbed “neo-burlesque,” the new genre combined elements of traditional burlesque with contemporary ideas from feminism and queer theory (a challenge to standard heterosexual ideas). As neo-burlesque took hold in Philadelphia, these themes came to dominate local burlesque. At the forefront, Anna Frangiosa (b. 1976) performed under the name Annie A-Bomb, beginning her career as a burlesque dancer with the burlesque group The Peek-A-Boo Revue in 1998. Later, she co-founded Cabaret Red Light, a troupe active between 2008 and 2011 that integrated elements of tongue-in-cheek agitprop—that is, overtly political art—into their burlesque shows, promoting what they called “pornographic socialism” with a stated goal of establishing “a carefully orchestrated, nonstop orgy on a national scale.” In 2009, Frangiosa founded the Philadelphia School of Burlesque in Fishtown. Outside of burlesque, Annie A-Bomb maintained an active political presence, participating in direct actions movements such as Occupy Philadelphia, a part of the larger Occupy Movement that protested economic inequality beginning in 2011.

Hallmarks of neo-burlesque included themes of sex-positivity, body-positivity, and queerness—that is, a radical non-assimilation to societal norms—often geared toward audiences of women. In empowering both performers and audience members, neo-burlesque returned to early burlesque’s liberatory potential for women, which had eroded with the dominance of male agents and audiences in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second decade of the twenty-first century saw the rise to prominence in Philadelphia of politicized burlesque performers, such as HoneyTree EvilEye (b. 1982), who actively incorporated more overtly political messages into their work. Concurrently, with the establishment of troupes like Bearlesque, Philadelphia burlesque expanded to incorporate more male-identified dancers. This trend was part of the development of the genre of boylesque—burlesque featuring eroticized portrayals of masculinity.

As the contours of American burlesque evolved throughout the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, Philadelphia performers kept pace. While often unjustly overshadowed by the larger New York burlesque scene, Philadelphia hosted established performers as part of a wider national and international burlesque circuit, and nourished local talent as well. Over the years, burlesque performers modified their routines—sometimes at their own discretion, sometimes at the behest of money-minded managers—to capture audiences’ changing tastes and expectations, intentionally defying those expectations at least as often as they met them.

Timothy Kent Holliday is a Ph.D. student at the University of Pennsylvania, where he studies the history of gender, sexuality, and the body in early America. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University