Common Sense

Essay

Published in Philadelphia in its first edition in January 1776, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense became one of the most widely disseminated and most often read political treatises in history. It looked forward to democratic politics and universal human rights, yet it also reflected local circumstances in Philadelphia. Common Sense was thus an overture to democracy and human rights as well as part of Philadelphia print culture and local politics.

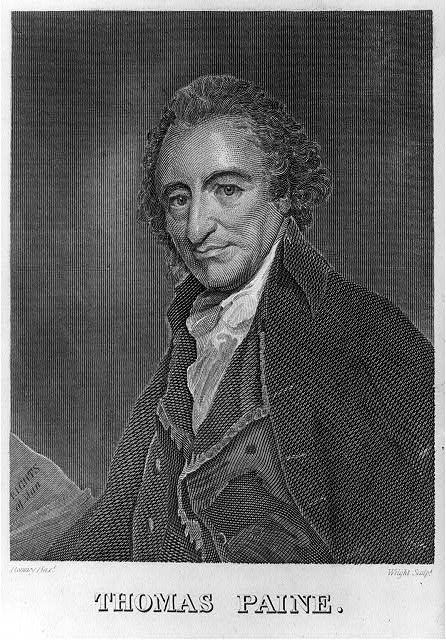

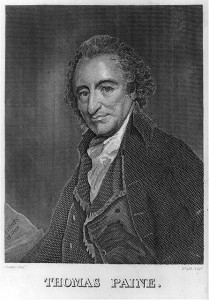

Born in England, Paine (1737-1809) adopted Philadelphia as a temporary home in November 1774, when he arrived with a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), whom he had met in London. Franklin recognized Paine’s skills as a writer and polemicist, and his letter helped Paine secure a position as the first editor of The Pennsylvania Magazine. In eight months as editor, Paine increased subscriptions and popularized colonial essays and poetry (as opposed to reprints of British material). Upon leaving The Pennsylvania Magazine, Paine was encouraged by Franklin and Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) to write Common Sense.

Philadelphia, the leading colonial political and mercantile city, was central to American resistance to exertions of British power in the 1770s. Delegates from most of the North American British colonies met in Philadelphia as the first Continental Congress in September and October 1774. A second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in May 1775, then declared independence in July 1776. Throughout 1776, Philadelphians feared invasion by water as well as by land. British ships blockaded Delaware Bay, while British soldiers moved south from New York through New Jersey toward Philadelphia. Appearing in the midst of this heightened political state, Common Sense found an audience in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

Attacking Traditional Authority

Paine’s renown in his own time and in later eras rested on his attack on traditional political authority and his defense of a radical form of democratic political participation. Paine had little inkling that politics dominated by white men would be, beginning in the nineteenth century, challenged by women and racial, ethnic, and sexual minorities. But he did define political participation and representation in ways that were in theory open to all. Much of American political thought after the War of Independence has entailed accepting or rejecting the notion of full political participation that Paine enunciated in Common Sense.

Paine’s arguments against traditional political authority dissected notions like the divine right of kings, the legitimacy of custom, the social value of aristocrats, and the ability of monarchs to ensure peace and prosperity for their subjects. Often Paine used familial metaphors such as King George III as a father who had turned against his children. The implication was that ordinary people, who had experienced familial relations, could make informed judgments about weighty political matters. He cast the situation in the Anglo-American colonies in 1776 as historic and universal. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” he wrote. “Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind are affected.”

Accordingly, in Common Sense, Paine cast himself as “under no sort of Influence public or private, but the influence of reason and principle.” His arguments for democratic politics rested on a broad suffrage, annual elections, and a large unicameral body of legislators. He aimed for representative government close to voters and responsive to their interests. Since the government recommended in Common Sense was a revolutionary alternative to the English Parliament, the British Crown, and the colonial royal governors and councils, then Paine’s conclusion was obvious. Reconciliation between Americans and the British government was impossible, and separation, independence, and unification of the colonies into a new nation should proceed.

First Edition Published Anonymously

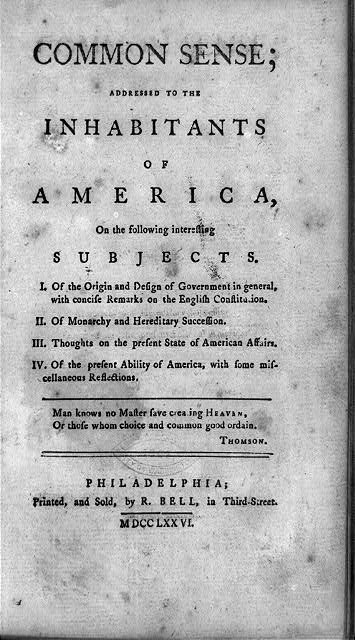

The form of government Common Sense recommended—a unicameral legislature with annual elections—was indeed crafted in 1776 by a Pennsylvania convention charged with writing a constitution for the new state. Most of the former colonies wrote new constitutions at this time as replacements for their colonial charters. The first edition of Common Sense was published anonymously by Scottish-born Philadelphia printer Robert Bell (c. 1732-84), who risked a charge of treason for disseminating the work. After arguing with Bell about profits and copyright, Paine appealed to Bell’s competitors, the Bradford Brothers, who published several enlarged editions, including the one most known to posterity, a third edition with new front and end matter and, for the first time, with Paine’s name on the title page. The wrangling over the work simply added to its notoriety. Moreover, Paine castigated Pennsylvania Quakers for mixing religion and politics in their appeals for peace. The book was quickly republished in a number of American and European cities.

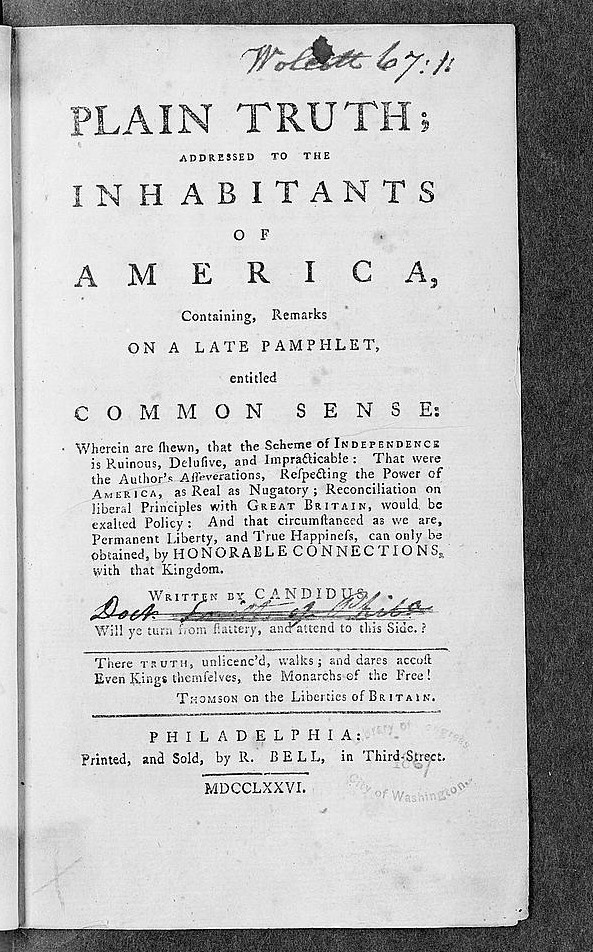

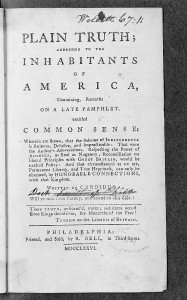

In the mid-1770s many Americans as well as many Philadelphians were torn between loyalty to the British empire and anger over the incursions of imperial power into the colonies in the late 1760s and early 1770s. Paine’s contemporaries (like modern scholars) perceived Common Sense as the decisive text that propelled colonial sentiment into independence. George Washington (1732-99), for instance, praised its “sound Doctrine, and unanswerable reasoning.” Edmund Randolph (1753-1813) wrote that after the dissemination of Common Sense, “public sentiment which a few weeks before had shuddered at the tremendous obstacles, with which independence was environed, overleaped every barrier.” Still, Common Sense also had critics, for example James Chalmers (1734-1806) in Plain Truth (1776, printed by Bell).

Paine continued to exhort for the patriot cause in a series of essays, American Crisis. Some of the language that Americans associate with the revolution—for example, “These are the times that try men’s souls”—flowed from Paine’s pen in these years. But in 1790 Pennsylvanians dismantled and modified their radically democratic government. A new constitution enacted mixed government, balancing a lower house with an upper house and a governor. By then Paine had moved to England (where he wrote Rights of Man) and then France (where he wrote The Age of Reason).

In sum, Common Sense was one of the most significant catalysts of the War of Independence as well as a bellwether of democratic thought. Although the radical structure of government that Paine recommended proved short lived in Pennsylvania, Americans at large have since the revolution grappled with some of the central concerns of Common Sense. Americans still contest the balance between popularly elected governments (both state and federal) and individual rights. Moreover, Paine, often called “a citizen of the world,” wrote in the American Crisis, “My attachment is to all the world, and not to any particular part.” His sense of world citizenship remains pertinent in the twenty-first century, an era of energetic human migration, instantaneous electronic communication, and global ecological interdependence.

John Saillant is Professor of English and History at Western Michigan University. He is the author of the monograph Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Revolutionary Politics (ExplorePaHistory.com)

- Books That Shaped America, 1750–1800 (Library of Congress)

- Creating the United States, Founded on a Set of Beliefs (Library of Congress)

- The American Enlightenment: From Royal to Republican (Stanford University Digital Collections)

- Democratic Origins and Revolutionary Writers, 1776-1820 (U.S. Department of State)

- Paine v. Chalmers: Was Declaring Independence Common Sense? (Smithsonian Associates)