Dentistry and Dentists

Essay

As dentistry slowly emerged as a profession in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, innovative dentists in Philadelphia helped to shape dental care, procedures, and tools. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, dental colleges, journals, and societies contributed to the expansion of dental training and practice, which gradually but increasingly became accessible to women and people of color.

Before the era of professional dentists, most minor dental complaints were handled within the household. Finnish naturalist Peter Kalm (1716-79) observed these folk dentistry practices while traveling through the American colonies. Writing from Raccoon, New Jersey, in 1749, he remarked: “The remedies against the tooth-ache are almost as numerous as days in a year. There is hardly an old woman but can tell you three or four score of them, of which she is perfectly certain that they are infallible and speedy in giving relief as a month’s fasting, by bread and water, is to a burthensome paunch.” Though skeptical of women’s popular medicine, Kalm listed a number of “effectual” American cures, including botanical remedies used by Native Americans. European colonists of all nationalities relied upon Native American knowledge to assess the pharmaceutical uses of new world plants. For example, Pennsylvania Germans learned from Native Americans how to apply a decoction of a tulip tree’s (Liriodendron tulipifera) root bark to cavities.

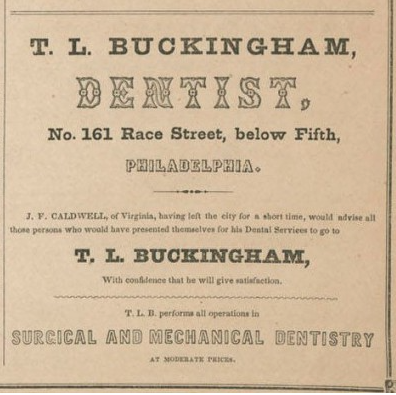

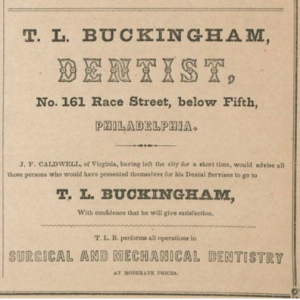

If a tooth could not be saved, eighteenth-century Philadelphians had several options. Doctors routinely performed extractions, but in the absence of a trained doctor, artisans handy with forceps, such as blacksmiths, might also suffice. The practitioners included enslaved people, such as the runaway sought by an advertisement in the 1740 Pennsylvania Gazette: “A Negro man named Simon, aged 40 years…” who could “Bleed and Draw Teeth… .” Doctors practiced dentistry into the nineteenth century, but beginning in the 1730s, individuals identifying as dentists advertised in American newspapers. On June 15, 1738, William Whitehead became the first in Philadelphia to place such an advertisement when he offered his services as an “Operator for the Teeth” in the American Weekly Mercury.

Itinerant Dentists

From the 1760s onward, an influx of formally-trained dentists arrived in Philadelphia from England and France. Some itinerants, like Robert Wooffendale, an immigrant from London, worked in temporary offices for weeks at a time. In advertising for patients, Wooffendale emphasized his training under Thomas Berdmore (c. 1740-85), who had served as dentist to King George III. By the end of the eighteenth century, these dentists offered diverse services ranging from teeth whitening to repairing scurvy-addled gums. Prices for dental work suggest that access to dentists may have been cost-prohibitive for many. In 1785, the well-regarded French dentist James Gardette (1756-1831) charged 11 shillings and 3 pence for a cleaning. This was slightly more than the cost of an evening’s concert ticket. However, charitable dentists such as James Molan (active in the 1790s) also treated impoverished Philadelphians for free.

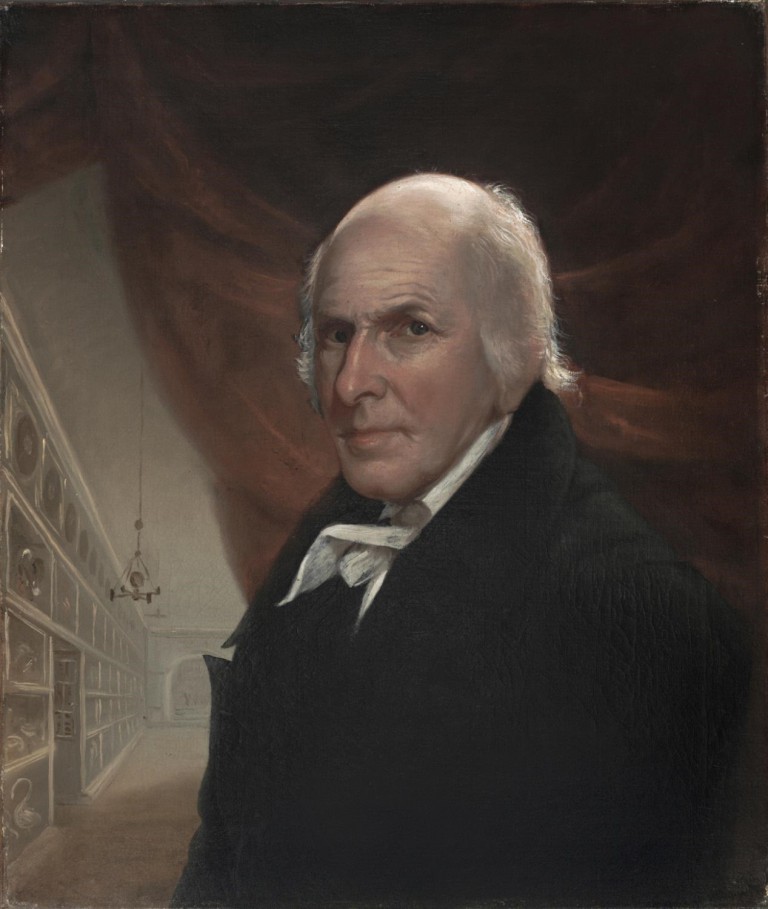

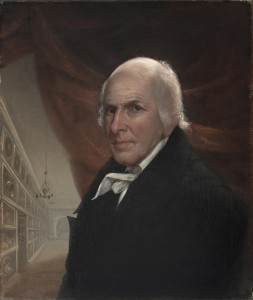

Individuals who extracted teeth or “plugged”–that is to say, filled cavities–often sold powders and instruments for home hygiene and cosmetics. In addition to boar-bristle brushes and scurvy lotions, their wares included false teeth made from a variety of natural materials. Making realistic, practical, and comfortable teeth required artistry. Painter and naturalist Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) carved dentures from ivory, the most common material for making teeth until about 1820. He later became an early experimenter with porcelain teeth. When he advertised porcelain dentures of his own design in 1826, local dentists responded by touting the superiority of their work. They included Frenchman Antoine A. Plantou, who very probably introduced what he called “incorruptible teeth” to Philadelphia in 1817. Incorruptible teeth were made of various inorganic materials, including porcelain, enamel, and minerals, although the exact composition varied with the manufacturer. Inorganic materials could withstand decay and wear far better than ivory, and thus became preferred materials for constructing dentures.

Many early innovations in dentistry emerged from the work of James Gardette (1756-1831), who improved the cosmetic appearance of dentures by using a mortised gold plate to mount one’s natural teeth. Gardette, a native of Agen, France, trained at the Royal Academy of Surgery in Paris in 1773-75 before becoming a surgeon in the French Navy. During the American Revolution, he was stationed in Newport, Rhode Island, where he first began practicing as a dentist. By 1784, Gardette had settled in Philadelphia, although he often worked itinerantly. Among his many accomplishments was the development of a procedure similar to extraction and reimplantation, in which he partially extracted a molar, severed and killed the nerve below, and allowed the tooth to reset in the gums. This allowed for a relatively painless filling afterward. Via this procedure, Gardette successfully determined that teeth could be replanted under particular conditions. Additional work in this vein demonstrated that it was not possible to transplant teeth from one human mouth to another.

Over 130 Dentists by 1845

By 1845, McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory listed more than one hundred and thirty dentists serving Philadelphia and one serving Camden, New Jersey. Some were second-generation dentists, such as Emile Blaise Gardette (1803-87), the son of James Gardette, and Gustavus Plantou, the son of Antoine Plantou. A number of these dentists had broad medical training, as denoted by their “M.D.” suffixes. Others, like James W. Newberry, were dentists and artisans. Newberry dabbled in watchmaking, likely because dental tools were versatile for fine jewelry work. Although the vast majority of the dentists listed in the 1845 directory were white, a handful of African American dentists operated in antebellum Philadelphia. They included James McCrummell (? – 1867), an abolitionist who in 1848 created a denture for an accused fugitive from slavery, Mary Walker (1818-95?). Walker was missing several of her front teeth, so the denture disguised a distinguishing feature of a suspected runaway.

Most medical colleges in Philadelphia offered courses and lectures on dentistry, but dental colleges did not appear until mid-century. The first was the short-lived Philadelphia College of Dental Surgery, which was founded in 1852 and became the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery in 1856, with Henry C. Carey (1793-1879) as president of the institution. By 1863, a second Philadelphia Dental College opened, followed by a dental school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1878. Some of these institutions admitted women. In 1869, German-born Henriette Hirschfield-Tiburtius (1834-1911) became the first woman to complete a full college course in dentistry when she graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. She returned home to practice as Germany’s first degreed woman dentist. Dentistry also became part of the curriculum at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, which was open to women of color. By the early twentieth century, Philadelphia’s independent dental colleges merged with local universities as Temple University acquired the Philadelphia College of Dental Surgery (1907) and the University of Pennsylvania absorbed the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery (1909).

Dental journals and societies marked the growing professionalism of dentistry. The most notable of the Philadelphia-based journals, The Dental Cosmos (1859-1936), became the most important national dental journal in the United States and later merged with the Journal of the American Dental Association. The Philadelphia County Dental Society met for the first time at the College of Physicians, then at Thirteenth and Locust Streets, on November 30, 1886. By 1899, a group of dentists on the other side of the Delaware River founded the Southern Dental Society of the State of New Jersey in Camden.

Dental Equipment Breakthroughs

The publisher of The Dental Cosmos, Dr. Samuel Stockton White (1822-79), also founded Philadelphia’s most successful dental depot. Established in 1844, for the next century the S.S. White firm offered functional and elaborately decorated dental tools and office furniture suitable for treating fashionable society. White’s company manufactured and sold dental engines, motor-operated machines with interchangeable heads for drilling and cleaning. A key component to the engines was a flexible rotary shaft. In contrast to a solid or fixed shaft, a flexible shaft allowed for more creative engine configurations. The realization that flexible shafts could be useful to aircraft manufacturers led the company to explore engine technology more broadly in the 1930s and 1940s. Other area companies contributed to the improvement of dental tools. In 1935, Wallace Carothers (1896-1937) invented nylon for Delaware-based chemical company DuPont, and nylon-bristled toothbrushes were introduced a few years later in 1938.

In the early twentieth century, the establishment of dental museums allowed local dental colleges to teach the history of dentistry alongside clinical practice. At their inception, these institutions consisted of collections of dental artifacts for the use of dental students. In 1915, the University of Pennsylvania acquired the Thomas W. Evans dental museum. Dr. Harold L. Faggart, D.D.S., both a practicing dentist and lecturer in dental history, helped to found Temple University’s dental museum in 1938. Faggart also donated some of his research on early dentistry to the Library Company of Philadelphia for the edification of the public. After extensive fund-raising efforts, Temple’s Dr. and Mrs. Edwin Weaver III Historical Dental Museum opened in 2003, allowing Temple’s collections to remain on permanent display. Its most notable holdings included the dental equipment of three generations of the Flagg family, but artifacts ranged from dental product ephemera to specimens of work created by former alums.

Dentistry continued to diversify in the early to middle twentieth century. In 1913, Latino students at the University of Pennsylvania founded the Latin American Dental Society. The following year, Penn admitted women to the School of Dental Medicine for the first time, yielding the school’s first class of women graduates in 1917. That same year, Carrie Kirk Bryant became the first woman to become an instructor in dental medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Helen E. Myers, D.D.S. (1912?-62), a 1942 graduate of Temple University, became the first woman to be commissioned by the U. S. Army Dental Corps. By 1952, women dental students at the University of Pennsylvania had founded their own dental society.

Growth of Dental Schools

As new areas of specialization developed and related professions, such as dental hygiene, emerged, dental campuses and enrollments expanded at Penn and Temple. In 1969 Penn added the Dental Research Building and the Levy Oral Health Sciences Building. By 2015, the University of Pennsylvania boasted more than 10,500 alumni of the dental school and offered both predoctoral and postdoctoral training in a variety of specializations. Temple’s Kornberg Dental School suffered a series of low ratings in the mid-1940s, but recovered by the 1980s and opened a sizable annex to its clinical facilities in 1990. Around this time, Temple faculty emphasized teaching new developments in cosmetic dentistry, as use of bleaching agents and veneers was becoming increasingly popular. Temple’s graduates maintained an active alumni community, with more than 7,000 members as of 2015. From the eighteenth to the twenty-first centuries, dentistry in Greater Philadelphia became increasingly characterized not only by how it was practiced, but also by who could be a practitioner.

Jessica Linker is a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and the recipient of fellowships from a number of Philadelphia-area institutions, including the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. Her work focuses on American women and scientific practice between 1720 and 1860. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University