Fort Wilson

By David Reader

Essay

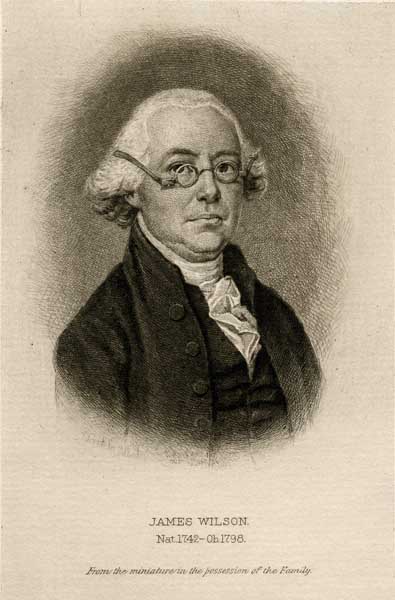

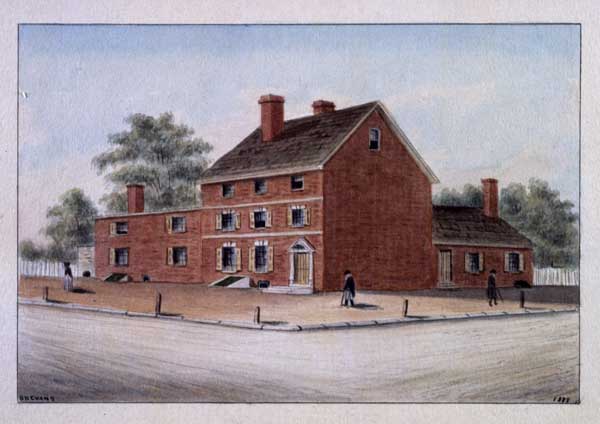

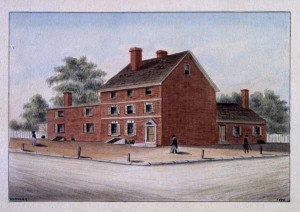

On October 4, 1779, the home of noted Pennsylvania lawyer and statesman James Wilson (1742-98) on the southwest corner of Third and Walnut Streets in Philadelphia became a flash point for Philadelphians divided by politics and class. The militia attack on “Fort Wilson” occurred in the wake of conflict over the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, rising inflation, and the recent departure of the British Army. Wilson had come to symbolize the complicated politics of Philadelphia during the American Revolution.

The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 created two factions, Constitutionalists and Republicans. The Constitutionalists favored the Constitution of 1776, which established a unicameral legislature, a weak executive branch, and a broadened suffrage to include any free male of 21 or older who paid even the smallest tax. The Republicans favored a two-house legislature, a suffrage restricted to adult male property owners, and a strong executive branch with legislative veto power. Wilson, a Republican, shared the view of his party’s disapproval of the radically democratic Constitution of 1776.

In January 1779, increasing prices of flour, wood, and grain renewed the demands by the Constitutionalists and working-class Philadelphians to impose price controls to stem inflation. But Wilson, Robert Morris (1734-1806), and the merchant class of Philadelphia benefitted financially from free trade and inflationary prices on such necessities. Throughout the spring and summer of 1779, the working-class and militia families who bore the financial and military burdens of the war looked on the merchant class with disdain for their lack of service and control of the economy. The rising tension between the classes led the working-class men in the Pennsylvania Assembly to favor price controls. The Philadelphia Committee of Privates, an organization of representatives from local militias and the working class created in 1775, re-emerged to secure price regulations and remedy other perceived acts of injustice by profiteers and Tories.

Militia Detains Merchants

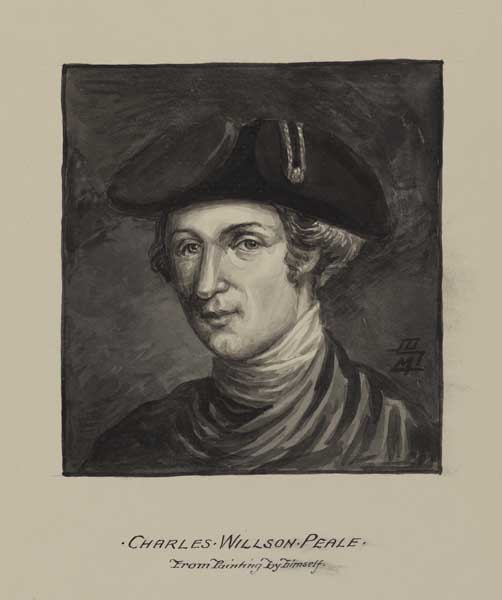

On Monday, October 4, 1779, a large number of militiamen gather at Burns Tavern on Tenth Street between Race and Vine Streets to take action against any man associated with profiteering and sympathetic to the British. Headed by Captain Ephraim Faulkner, the militia called on Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) to lead their march through the city to arrest and detain their enemies. As some cried out, “Get Wilson,” Peale tried but failed to persuade the militia to abandon the plan. The militia captured four prominent merchants and forcefully marched them through the streets of Philadelphia in a display of public humiliation.

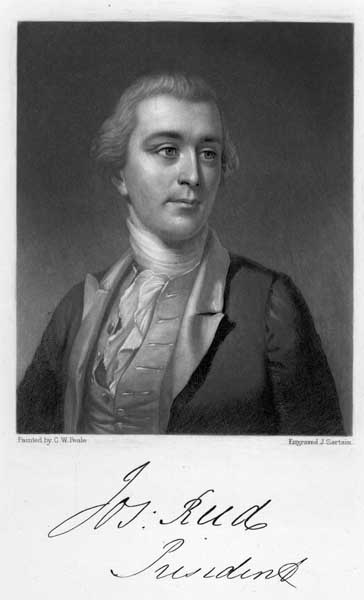

To avoid being captured by the militia, Wilson and other members of the Republican Society barricaded themselves inside Wilson’s house. The militia stopped near Wilson’s house when Captain Robert Campbell (1753-79), who was inside, opened a window and either shouted to them to continue marching or shouted and fired his pistol at the militia. Storming the doors, the militiamen set fire to the first floor and killed Campbell before being turned away by the men inside. The arrival of Joseph Reed (1741-85), President of the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council, and the City Troop of Light Horse ended the attack on Fort Wilson. Four militiamen, one free Black youth (who joined the militia’s march), and Captain Campbell were killed, and fourteen militia and three men from inside the house were wounded.

The arrest of several militiamen increased the tension throughout the city and surrounding areas. Wilson fled the city to Morris’s country estate until October 19, 1779, when he returned to the city at night. The Pennsylvania Assembly acted quickly to quell the tension between the classes through legislation that provided flour to the families of the militia and re-emphasized the enforcement of the laws pertaining to military service. In March 1780 the Executive Council passed an act pardoning all involved in the attack on Fort Wilson.

David Reader teaches history at Camden Catholic High School and was the recipient of the James Madison Memorial Fellowship in 2007. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University