Free Black Communities

Essay

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia and the region surrounding it came to contain free Black communities that by most measures were the most vibrant, dynamic, and influential in the United States. Free African Americans relied on each other to confront the persistent power of slavery and white supremacy in Philadelphia and the region. At the same time, many free Black people looked outward and became leaders in the national fight against those same threats.

The emergence of these communities was not, however, a foregone conclusion. In the mid-eighteenth century, despite the fact that Philadelphia had produced some of the earliest protests against slavery in the English-speaking world, slavery remained an important part of the region’s economy. In 1765, of the approximately fifteen hundred Black Philadelphians, all but about one hundred were enslaved. In the next few decades, though, this dramatically changed. The causes of this transformation were multiple. Some supporters of the revolutionary cause came to recognize a clear contradiction between their calls for liberty and the practice of slavery. Others, in particular some of Philadelphia’s significant Quaker minority, grew to see slavery as a violation of deeply held religious beliefs. Perhaps most of all, the Revolutionary War presented opportunities seized by African Americans across the region. Many supported the British Army as the most likely agent of emancipation, others supported the patriot cause in hopes of turning the American Revolution into a war for emancipation, and still others took advantage of the chaos of war to escape from their masters’ control. By the end of the American Revolution, Philadelphia contained only four hundred slaves while its free Black population had grown to over one thousand.

In the revolutionary era, the governments of many of the states acted to emancipate their remaining slaves. Massachusetts and Pennsylvania led the way, with Pennsylvania instituting a “gradual” abolition law in 1780. The law freed no one immediately, but it stipulated that all enslaved children born after the law’s passage would become free upon their twenty-eighth birthday. In New Jersey, opponents of slavery pushed for similar legislation, although the political power of slaveholders in the eastern part of the state, combined with fears of the social and economic consequences of emancipating New Jersey’s sizable enslaved population, prevented the passage of an abolition bill until 1804. Its implementation also took place gradually; children born after July 4, 1804, to enslaved mothers were bound to service for twenty-five years if male and twenty-one years if female.

A Growing Free Black Population

Over time, these abolition laws, combined with the continuation of private manumissions of the Philadelphia region’s remaining slaves, led to the growth of a free Black population, but a significant number of free Black people also found their way to Philadelphia from elsewhere. The economic and political power of slavery blocked abolition laws in the upper South. However, a significant number of slaveholders, including some in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, began to manumit some of their slaves in response to ideological critiques of slavery and changing regional economics. Slaves themselves played a crucial role in this process, often negotiating contracts in which they themselves would, over time, purchase their own freedom, while others found opportunities to disappear into the region’s growing free Black communities.

Many newly freed men and women found that their native states, while happy to take advantage of enslaved labor, did not welcome free Black citizens. Some required emancipated slaves to leave the state, and others placed increasingly restrictive controls on free Black people. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, as many former slaves found their way to Philadelphia—the nearest free city to the slave South—the city’s free Black population swelled. In 1780, the year the state passed its abolition law, African Americans (most of them enslaved) made up 3.6 percent of the population of the city. By 1820, the Black population had grown to more than 10 percent of Philadelphia’s total population. In the same year, free Black people up more than 6 percent of the population in Chester County and 7 percent of the population in Delaware County. Free Black residents accounted for more than 15 percent of the population in New Castle County, Delaware. In New Jersey, Salem County’s free Black population topped 7 percent, while Burlington and Gloucester Counties contained more than 4 percent free African Americans.

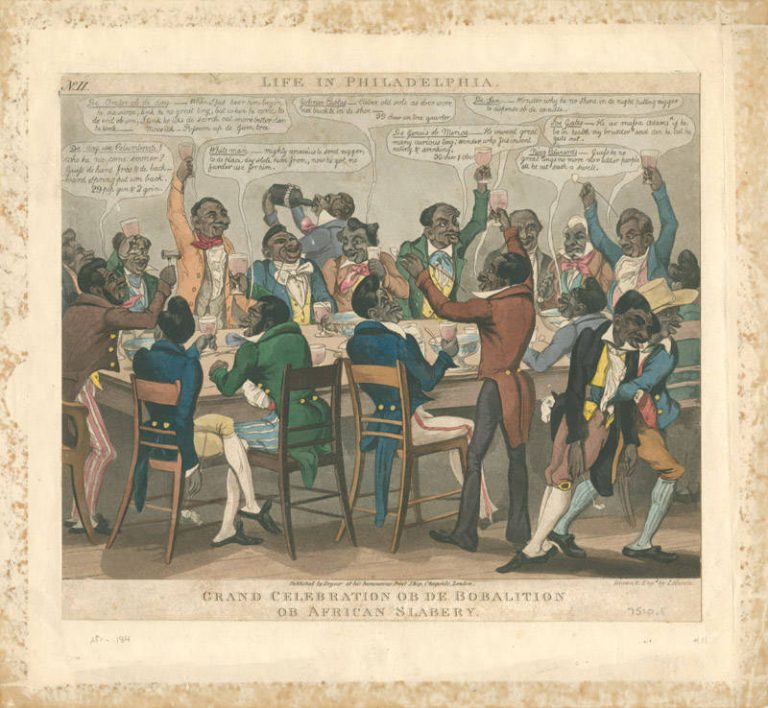

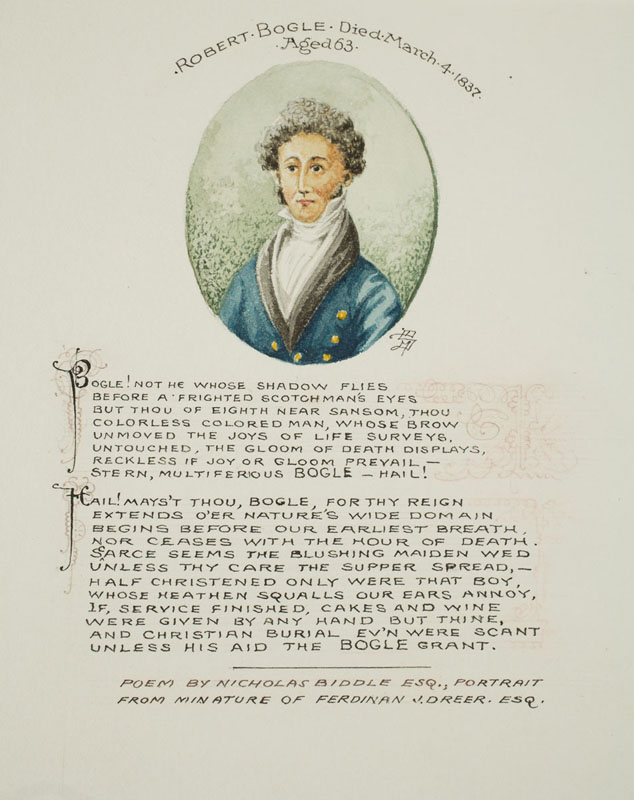

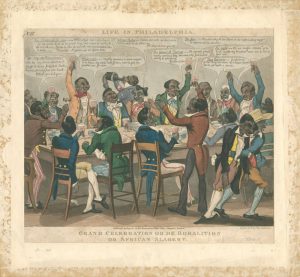

One of the great draws of Philadelphia was the lure of economic opportunity. Newly emancipated African Americans from rural areas across the region and beyond saw promise in the burgeoning city. Once there, though, they often found that they were shunted into the lowest paying and least desirable kinds of work. This was compounded by the fact that Philadelphia was also a magnet for European immigration, creating fierce competition for low-wage work. While white workers found employment in the city’s robust industrial sector, free Black people were largely excluded from this sort of work and relegated to employment as physical laborers and in the low-status service economy. Many free Black people worked on the city’s docks and aboard the ships that plied the Delaware. There were, however, some Black Philadelphians who found a greater measure of economic success. Some were professionals, especially teachers and ministers. Others were entrepreneurs. Among the most celebrated Black businessmen was James Forten (1766-1842), whose sailmaking business thrived in Philadelphia’s multiracial waterfront. The most successful Black waiters and caterers also were able to capitalize on their expertise and skill in order to establish themselves as an indispensable part of Philadelphia high society. Perhaps the most famous of these was Robert Bogle (1774-1848), celebrated by financier Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844) in a poem, Ode to Bogle.

Limited Opportunities

New Jersey also saw the growth of thriving Black communities in this period, including all-Black towns such as Tumbuctoo in Burlington County, Gouldtown in Cumberland County, and the Free Haven settlement that evolved into Lawnside in Camden County. Slavery’s end was slower in New Jersey than in Pennsylvania, casting a shadow over the free Black population. Free Black people often found themselves working alongside the enslaved in a complex labor market. As was the case in Philadelphia, in New Jersey, newly emancipated African Americans struggled to achieve independence in the face of significant limitations on their economic opportunities. Most of those who farmed did so as tenants, but a significant minority purchased their own farmland. Even so, this land was often economically marginal and whether they lived in cities or in the countryside, Africans Americans found their economic status to be tenuous.

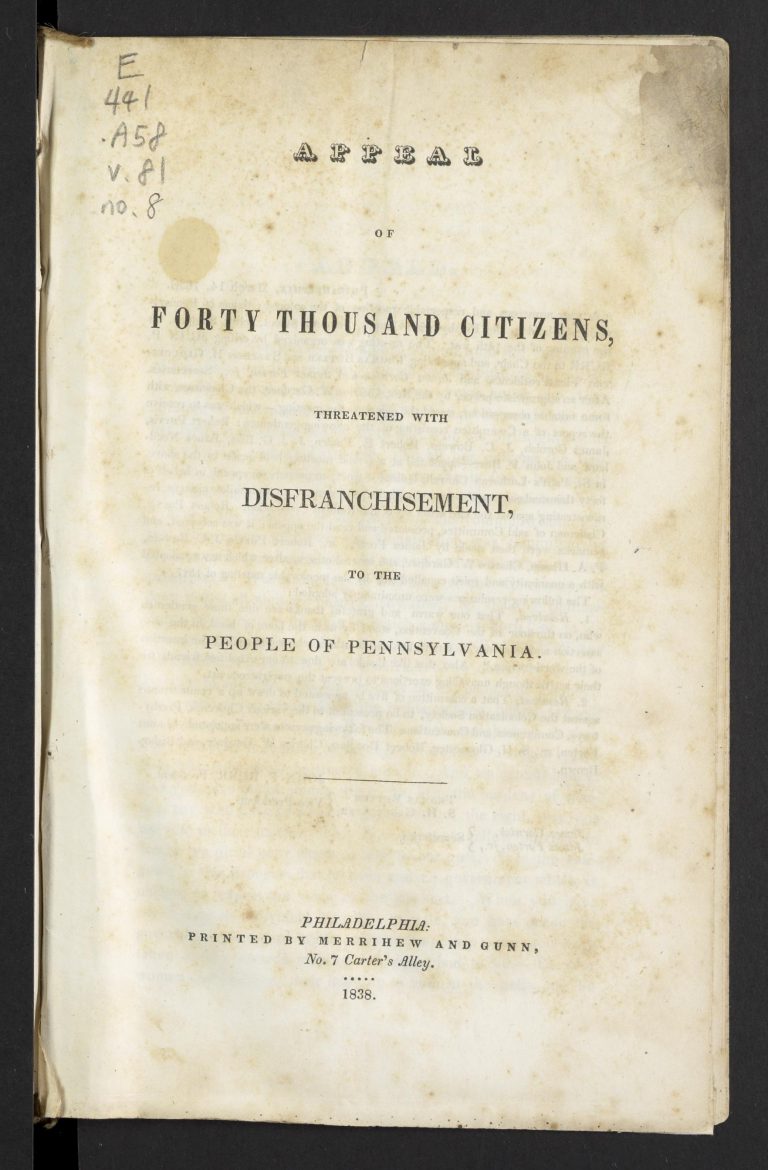

The dramatic growth of the region’s free Black population provoked anxiety among many of the region’s white residents. Pennsylvania legislators sought on multiple occasions to stop Black migration into their state but were thwarted by the cooperative activism of Black and white abolitionists. Free Black residents also faced the persistent threat of mob violence, which was often directed at Black abolitionists and at evidence of Black economic success or social respectability. New Jersey officially denied the vote to Black people in 1807. In 1838, the voters of Pennsylvania ratified a new state constitution which explicitly restricted the vote to whites. Black Pennsylvanians had attempted to prevent this action, publishing The Appeal of 40,000 Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, written by Black abolitionist Robert Purvis (1810-1898), but were unsuccessful and would not regain the right to vote until 1870.

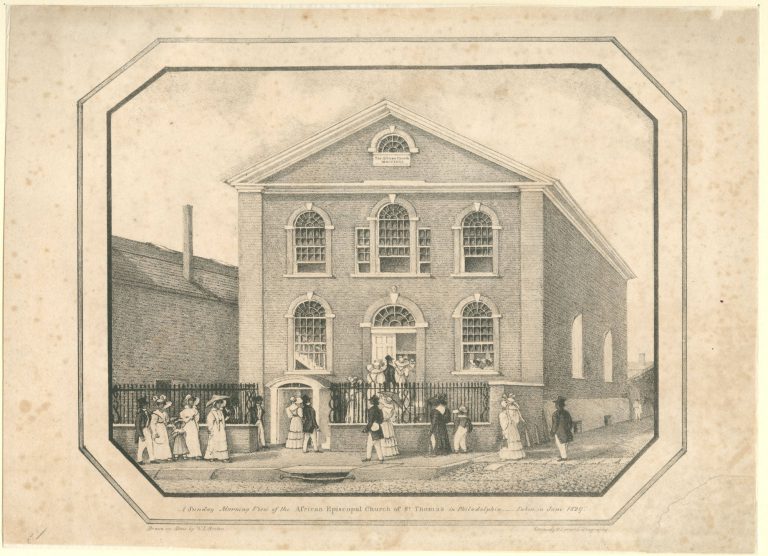

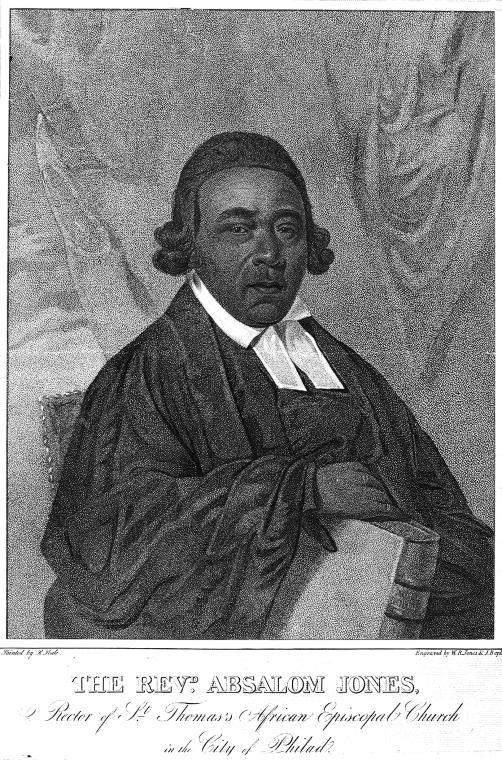

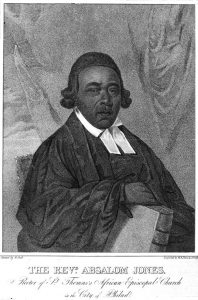

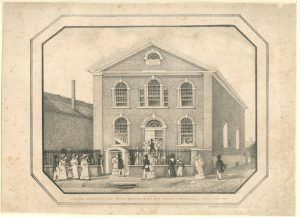

One of the primary ways that free Black people dealt with such economic, social, and political discrimination was through the building of autonomous institutions. One of the first of these was the Free African Society, founded in 1787 by leading Black citizens of Philadelphia including pastors Richard Allen (1760-1831) and Absalom Jones (1746-1818). This religious mutual aid society was a means of organizing the efforts of Black Philadelphians to promote education, and generally to provide aid to those in need. Allen and Jones would go on to found their own independent Black churches, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, only the first of many Black congregations in the city and the region. Black Philadelphians also helped to establish institutions that extended beyond the region, including the African Methodist Episcopal Church, an independent Black denomination co-founded by Allen in 1816. Many African Americans joined Black fraternal organizations and intellectual clubs, especially in Philadelphia but also in smaller Black communities across the region. Black Philadelphians played a leading role in the Black Convention Movement, which brought together Black leaders from across the United States to strategize about political issues.

Vigilante Protectors

Perhaps the most urgent goal of free Black communities, especially in regions like greater Philadelphia that bordered on slave states, was the protection of Black citizens from enslavement, kidnapping, and white violence. Black communities were constantly on the lookout for those who generally claimed to be acting as legal slave catchers but who often were willing to kidnap the legally free as well. African Americans resisted such men with force when necessary, but along with white allies they also banded together to form some the earliest vigilance committees, dedicated to the protection of the Black community from such threats. These committees played a crucial role in what would come to be called the Underground Railroad. Philadelphia, with its large Black population, was a center for such activity, but across the region fugitives from slavery and vulnerable free Black people sought out the protection of Black communities and partnership with supportive whites, often Quakers. Free Black people also worked with white abolitionists who could provide essential legal and political expertise, including those who had established the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1775. While many early white abolitionists had seen the removal of free Black people from the United States as a necessary part of their fight against slavery, Black abolitionists, especially Black Philadelphians, played a crucial role in radicalizing white abolition and in convincing white abolitionists to abandon the colonization movement. Black abolitionists coupled their opposition to slavery with demands for Black equality, and they supported white abolitionists who did the same.

Free African Americans made up a significant portion of the population of the greater Philadelphia region during the decades between the American Revolution and the Civil War. Such numbers, though, only tell part of the story. The Black community of Philadelphia played a critical role in the history of the city, and Black Philadelphians helped to lead the cause of abolition and the fight for Black citizenship rights, in the city and beyond.

Andrew Diemer is Assistant Professor of History and Director of Metropolitan Studies at Towson University. He is author of The Politics of Black Citizenship: Free African Americans in the Mid-Atlantic Borderland, 1817-1863 (University of Georgia Press, 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Philly celebrates Richard Allen, forefather of civil rights, and stamp with his likeness (WHYY, February 2, 2016)

- Black History Month youth essay contest doubles as a way to honor 'unsung heroes' (WHYY, February 17, 2014)

- Underground Railroad tour in Germantown offers 'hidden history' lessons (WHYY, October 14, 2014)

- Artifacts of NJ town run by freed slaves in New Jersey on display (WHYY, February 13, 2015)

- A painting found in a Glenside thrift store came out of Philly's 19th-century Black cultural elite (WHYY, January 6, 2025)

Links

- African American Museum in Philadelphia

- Black Founders: The Free Black Community in the Early Republic (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Preamble of the Free African Society, 1787 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Absalom Jones Portrait, 1810 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793 (PBS)

- Richard Allen: Apostle of Freedom (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Antebellum African-American Settlements in Southern New Jersey (African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter, December 2009, PDF)

- Excavation of sites such as Timbuctoo, N.J., is helping to rewrite African American history (Washington Post, August 3, 2010)

- Timbuctoo, New Jersey

- Gouldtown: A Very Remarkable Settlement of Ancient Date (New York Public Library)