Grand Juries

Essay

The grand jury, enshrined in common law and inscribed in the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, has represented a force for citizen participation in the judicial process as well as for government power. The grand jury has the power to indict in felony cases and the broad right to investigate crimes. Although Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey did not include the right to a grand jury in their first state constitutions (only North Carolina and Georgia did), their legislatures passed laws authorizing grand juries. Grand jury cases and decisions provide a window into the social, political, and legal issues that have engaged the region.

Fears of threats to the survival of the new republic motivated several early Pennsylvania grand juries. The nation’s earliest grand jury, which met in Philadelphia in 1778, indicted twenty-five British sympathizers for treason. Philadelphia grand juries helped establish the limits of free speech in two famous libel cases, against journalists Eleazer Oswald (1750–95) in 1782 and William Cobbett (1763–1835) in 1799. Eastern Pennsylvania circuit court grand juries responding to popular uprisings in western Pennsylvania and in the hinterland north of Philadelphia indicted dozens of participants in the 1795 Whiskey Rebellion and the 1799 Fries Rebellion for treason.

As Philadelphia’s population grew, in part due to an influx of European immigrants and African American fugitives from slavery, grand juries grappled with issues of race, ethnicity, and religion. In 1838, Philadelphia grand jurors indicted two rioters responsible for burning down the antislavery meeting house Pennsylvania Hall, though they blamed radical abolitionists for inciting the riot. A few years later, in 1844, riots sparked by Catholic opposition to the use of Protestant Bibles in public schools erupted in Kensington against Irish Catholics. A Philadelphia grand jury eventually indicted nineteen rioters (only a handful were convicted), but castigated the victims. In 1851, a circuit court grand jury in Lancaster County heard the case that resulted from the Christiana Riots, which tested the federal Fugitive Slave Law. Though it indicted thirty-eight men who had refused to aid a federal marshal in seizing a fugitive slave for treason, none were convicted, on the basis that neither self-defense nor refusing aid was an attack on the nation.

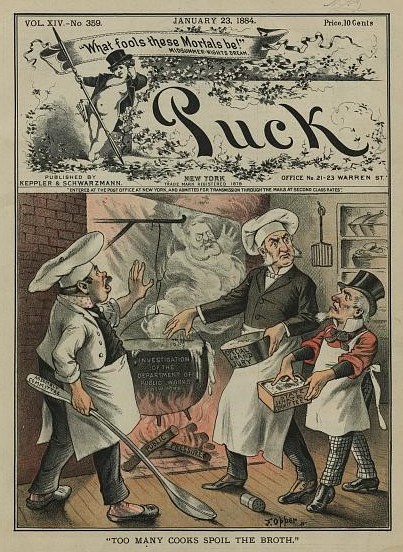

Important Philadelphia grand juries in the twentieth century addressed the city’s experience with racketeering and corruption, a scourge that contributed to Philadelphia’s reputation as “corrupt and contented.” Federal and state grand jury investigations and indictments ameliorated this reputation to some extent. In 1928, a grand jury on bootlegging found 138 police officers unfit to serve, though the grand jury’s report did not lead to charges against any bootleggers. Grand juries continued to investigate city corruption into the 1950s. Corruption within the Republican-controlled city government was the subject of several grand jury investigations supported by Democratic reformers Joseph S. Clark (1901–90) and Richardson Dilworth (1898–1974). The findings of a special grand jury that convened from 1948 to 1951 to investigate city corruption led to numerous indictments and several suicides and helped Clark win the mayor’s race in 1951.

Despite their incorporation of citizen concerns and viewpoints into the legal process, however, grand juries have faced criticism. During the Vietnam War era, the federal government used, and sometimes misused, grand juries to indict war protesters and suppress dissent, as in the case of two grand juries in Harrisburg in 1971 that brought questionable conspiracy indictments against the Harrisburg 7, including Catholic priests Philip (1923–2002) and Daniel Berrigan (1921-2016), and the Camden 28, including Father Michael Doyle (b. 1934) of Camden. In both cases, juries later acquitted the defendants.

Because of complaints about their secrecy—and to make the filing of charges consistent across the state—Pennsylvania became one of only two states, through a pair of acts in 1974 and 1976, to abolish indicting grand juries. (It retained investigative juries, and federal grand juries continued to have the power to indict.) That power was restored by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, however, in 2012, in response to widespread witness intimidation at public preliminary hearings in Philadelphia.

Police misconduct and organized crime were the targets of Philadelphia grand jury investigations in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1984 and 1995, they led to numerous convictions for abuse of police authority. Philadelphia’s ties to the notorious Genovese and Gambino crime families were highlighted by the federal grand jury indictments of Philadelphia mob bosses Nicodema Scarfo (b. 1929) and John Stanfa (b. 1940) in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

One of the most important political corruption cases handled by a Philadelphia grand jury was the Abscam case. In 1980, a federal grand jury in Philadelphia handed down the first indictments, against council president George X. Schwartz (1915–2010), council members Harry P. Jannotti (1924–98) and Louis C. Johanson (1929–2004), and lawyer Howard L. Criden (1926–92). Several politicians from southern New Jersey were indicted by grand juries elsewhere. State and national representatives from the region have also been the subjects of grand jury investigation. A federal grand jury indicted Pennsylvania state senator Vincent Fumo (b. 1943) in 2007 and U.S. Representative Chaka Fattah (b. 1956) of Philadelphia in 2015, both for public corruption and fraud.

New Jersey and Delaware have not been immune from similar investigations. New Jersey grand juries have indicted several mayors for official misconduct, including, in 1990, Mayor James L. Usry (1922–2002) of Atlantic City. In Delaware, a Wilmington grand jury indicted Thomas Capano (1949–2011), a former assistant district attorney, in 1997 for the murder of Anne Marie Fahey (1966–96), the then-governor’s scheduling secretary. His sensational trial resulted in a death sentence for Capano, who later died in prison. In 2014, a New Castle County grand jury indicted employees of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for drug trafficking and tampering with evidence, endangering thousands of drug cases.

In the twenty-first century, grand juries in the region have continued to wrestle with issues of right and wrong. Among the most important investigations was that of a 2003 Philadelphia County grand jury into sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy and Archdiocesan employees. The investigation lasted longer than the jury’s three-year term and had to be continued by a newly empaneled jury. The final report, released in 2011, recommended significant institutional and legal reforms and identified credible accusations against thirty-seven priests as well as a large-scale cover-up. It led to the conviction of Monsignor William Lynn (b. 1951) in the cover-up (later overturned on appeal), trials of other abusers, and numerous civil suits by abuse survivors. Sexual abuse of minors was also the subject of a 2010 Delaware grand jury investigation that led to the indictment of pediatrician Earl Bradley (b. 1953) of Lewes, Delaware. Attorney General Beau Biden (1969–2015), son of Vice President Joe Biden (b. 1942), declined to run for this father’s former Senate seat in order to see this case, involving sex crimes against 103 children, through to its conclusion.

Throughout the region’s history, grand juries have reflected citizens’ and government’s concern about such issues as sedition and the limits of legitimate dissent, race and ethnicity, and racketeering and public corruption. Grand juries in the Philadelphia region have both provided citizens a voice in the judicial process and been used to stifle certain voices, all while illuminating the moral issues that have faced the nation.

Linda Myrsiades is professor emerita of English and comparative literature at West Chester University of Pennsylvania and the author of several books. Her most recent works include Law and Medicine in Revolutionary America, Medical Culture in Revolutionary America, The Culture of Abortion in Literature and Law, and Cultural Representation in Historical Resistance. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History