Lawnside, New Jersey

Essay

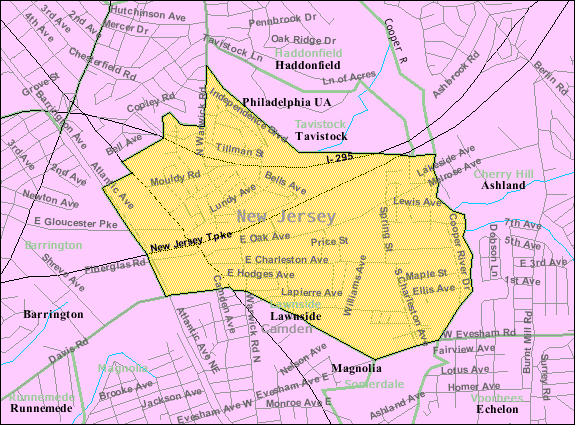

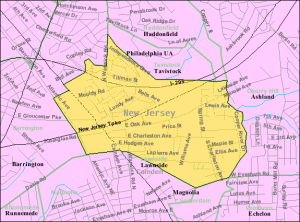

Located approximately nine miles from Philadelphia and with a population of 2,995 as of 2010, Lawnside, New Jersey, has been one of only a handful of jurisdictions in the United States that has maintained a primarily African American population throughout its existence. Formed out of the experience of slavery, the community evolved during the twentieth century into a thriving suburban enclave despite the widespread Jim Crow discrimination that existed in New Jersey until the civil rights campaigns of the 1960s.

In the eighteenth century, New Jersey’s burgeoning industrial and agricultural enterprises generated a great demand for labor, one result of which was the importation and use of enslaved laborers of African ancestry. The presence of slavery in Camden County was mitigated by the abolitionist influence of the Haddonfield Monthly Meeting of the Quaker Society of Friends in conjunction with the Gloucester County Abolition Society. Due to their efforts, the number of slaves in Camden County dropped by more than two-thirds between 1790 and 1800, from 191 to 63.

Seeking to foster mutual aid and collective security from the widespread threat of kidnapping and return to enslavement, freedmen sought protection by concentrating near Quaker allies in Camden County. For example, people formerly enslaved by the Hugg family founded the community of Guinea Town in the area that later became Bellmawr in the late eighteenth century, and others founded the settlements of Davistown and Hickstown in Gloucester Township. Saddlertown in Haddon Township was founded by Joshua Saddler (1785-1880), whose freedom was purchased by Friends at the site that became Croft Farm in Cherry Hill. Over time the free African American population of Camden County more than doubled between 1790 and 1810, from an estimated 180 to 490, and continued to grow to 1,104 by 1840. In old Union Township, where the original settlement that became Lawnside was located, 22 percent of the population was African American.

African American habitation in Lawnside dated to the eighteenth century. Organized Methodist meetings began in 1797, and in 1811 Philadelphia’s Bishop Richard Allen (1760-1831) formed an African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) Church that later became Mount Pisgah AME Church. The majority of the residents served by these institutions were formerly enslaved people or their descendants. The original male inhabitants worked mostly as farmers and woodcutters, and some women earned income as domestic workers.

First Known as Free Haven

In 1840, a Quaker abolitionist and member of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee named Ralph Smith further advanced the prospects for settlement by purchasing land to convert into inexpensive lots for sale to African Americans. A prominent African American barber, physician, dentist, and community leader from Philadelphia, Jacob C. White Sr. (1806-72), also contributed to Lawnside’s early development by purchasing additional land to expand the village. The community was first named Free Haven because it served as a stop and way station along multiple routes of the Underground Railroad. By 1856, the area had grown to support at least twenty-four buildings.

Shortly after the Civil War, Free Haven’s name changed to Snow Hill, reportedly for the prominence of sugar sand atop the hill where early settlement formed. Following the arrival of the Philadelphia and Atlantic Railroad (later the Reading Railroad) in 1876, the name of the stop changed from Denton to Lawnton and finally Lawnside in 1907. Often attributed to the beautiful sloping lawn that adjoined the station, the name was adopted by the community to conform with the new rail stop.

On March 24, 1926, Lawnside was incorporated as an official borough in the state of New Jersey as part of the broader trend of municipal incorporation in Camden County. Located on unincorporated land in old Centre Township from 1855 to 1926, Lawnside as well as other nearby communities felt the need to incorporate. Lawnside’s incorporation bid experienced boundary disputes with both Barrington and Haddonfield. Lawnside resolved matters with Barrington by ceding 170 acres of land along the Clements Bridge Road in exchange for a parcel that included the Mt. Peace Cemetery on the White Horse Pike. With Haddonfield, the issue concerned two parcels with high assessments inhabited by whites who did not want to be included in Lawnside because it was to be governed by African Americans. The parties reached settlement when Lawnside officials handed over the land in exchange for $25,000 payable in five yearly installments.

A small number of whites still remained within Lawnside’s newly incorporated boundaries in an area known as Woodcrest. These families sent their children to Delaware Township schools until 1931, when this municipality began demanding tuition payments for the accommodation of these children. The Woodcrest residents refused to then send their children to the Lawnside elementary school and responded by burning crosses in Lawnside and then launching a failed bid for incorporation as an independent borough. The situation was resolved only when these residents moved out of Lawnside.

Demographics Prevail

Lawnside’s act of incorporation did not designate it as an African American community. Its demographics in 1926, however, allowed African Americans to control the municipal power structure, and its historical trajectory allowed this to continue. After incorporation, residents worked hard to develop new institutional facilities such as a borough council and police force to add to an existing volunteer fire department, post office, and elementary school dating back to 1848.

The town’s rail connection to a string of communities from Philadelphia to Atlantic City opened up employment and travel opportunities for some residents, while also drawing visitors to the community and offering employment to African American professionals such as teachers who lived in other communities. Despite these transportation links, Lawnside remained a largely rural and agricultural community until World War II, when many men gained employment from defense industry jobs. Women in Lawnside commonly worked as domestic workers in nearby communities such as Haddonfield and Haddon Heights.

Many Lawnside residents attained the American dream of home ownership despite a long history of banks refusing loans to African Americans. In 1909, the Home Mutual Investment Company incorporated in Lawnside to help residents secure mortgages and financing for the construction of homes. It was succeeded in 1915 by the Lawnside Mutual Building and Loan Association. Residents benefitted in the early years of Lawnside’s incorporation by having almost no political red tape for housing construction. Most addresses in the community were simply made up by the homeowners, and there were no restrictions placed on the building of homes on vacant land. Despite such informal control over land use, by the postwar period Lawnside’s rural character began to give way to an advancing suburban look and feel.

Lawnside’s existence and reputation as a distinctive Black community was supported in the 1930s through the presence of a thriving jazz and barbecue scene in the wake of prohibition with venues named the Cotton Club, The High Hat Club, Dreamland Café, and Club Harlem. These establishments attracted patrons from all over the northeast to hear and rub shoulders with top African American performers and celebrities such as Joe Louis (1914-81), Sarah Vaughn (1924-90), Ella Fitzgerald (1917-96), Duke Ellington (1899-1974), Billie Holliday (1915-59), LaWanda Page (1920-2002), Billy Eckstine (1914-93), and Arthur Prysock (1929-97). Arnold Cream (1914-94) worked as a bouncer at the Dreamland Café before becoming heavyweight champion of the world under the fighting name Jersey Joe Walcott.

The Lure of Lawnside Park

Lawnside’s proximity to Philadelphia and reputation as an African American cultural and community space drew talented artists and patrons to the community. Lawnside also attracted visitors because of Lawnside Park, an amusement park and picnic area with two small man-made lakes that began to be developed in the late 1920s. These venues thrived for years, until the 1960s when the clubs and associated dining establishments declined and ultimately closed. Lawnside establishments could no longer compete with the high rates that desegregated mainstream clubs could pay to high-profile African American performers. Lawnside’s conservative and religious community character also played a role in the clubs’ decline, as most locals stayed away from places with reputations for vice and lewd conduct.

At a time when both federal loan procedures and suburban zoning restrictions limited choices for Black home ownership, Lawnside’s attractive location and status as an autonomous African American community boosted further settlement. The newcomers included returning servicemen, government employees, and professionals who could afford to purchase new homes constructed in Lawnside by developers. For example, Howard University graduates Dr. William Young Sr. and his wife Dr. Flora Young (1928-2012), a professor at Glassboro State College (later Rowan University), moved to Lawnside in 1954 when Dr. William Young opened a medical practice in Lawnside. The Friendship III Barber Shop, opened in 1959 by its founder Percy Bryant (b. 1938), became a thriving gathering place that provided an essential service for African American men, including celebrities such as Muhammad Ali (1942-2016).

Lawnside grew at a rapid pace in the 1950s and 1960s with the construction of new housing developments. The first, Home Acres (1954), consisted of modest homes and contributed to an increase in population by 369 residents between 1950 and 1960. From 1960 to March 1970, an additional 273 housing structures went up and the population rose from 2,155 to 2,757. This included the stylish Warwick Hills development, which featured modern two-story homes. Commercial investment increased the town valuation 2,000 percent in just a six-year span from 1967 ($1 million) to 1973 ($21.5 million).

Without a secondary school of its own, as far back as 1916 Lawnside sent some of its young people to nearby Haddon Heights High School, where they paid a per-pupil flat rate tuition fee after 1924. As a distinct minority within the school, children from Lawnside experienced a great deal of discrimination in academics, athletics, extracurricular activities, and school culture. Academically, they were frequently steered into general level courses and discouraged from pursuing the college preparatory track. Although the baseball, football, and basketball teams integrated in 1922, many African American athletes were discouraged from participation. African American students were never elected prom or homecoming king or queen until the late 1970s, few participated in student government or the yearbook, and school dances remained the domain of whites until the 1960s.

Youth Embrace the Rights Movements

As young people in Lawnside were influenced by the wider civil rights and Black power movements of the 1960s, they bridled at the discrimination they experienced in school. From 1965 to 1971, students from Lawnside, including several young women, led sit-ins and protest marches, issued demands, served as media spokespersons, and wrote politically themed articles in the student newspaper. These activist efforts took place with little direction from Lawnside parents, civic leaders, or African American organizations. They were successful in forcing a change in the school administration, gaining more equitable representation in student life, instituting Black studies courses, and forming the Afro-American Cultural Society.

As integration progressed, African Americans from Lawnside played important roles in the larger society. Morris L. Smith (b. 1933) had a long and distinguished career as an executive at Scott Paper company. As president of the Lawnside Board of Education he orchestrated a resolution on April 9, 1968, that declared the birthday of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-68) a holiday. Lawnside civic leaders believe they were the first governmental entity in the United States to bestow this honor, just days after King’s assassination. One of Smith’s sons, Morris G. Smith (b. 1960), developed a successful law firm, served as both a state and federal court judge, and was the vice chairman of the New Jersey State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights. Wayne Bryant (b. 1947) created a thriving law practice in Camden, served as an assembly member in New Jersey (1982-95) and state senator (1995-2008), before being jailed on corruption charges. Always a welcoming place for other racial and ethnic groups, Lawnside acquired a small degree of diversity in the latter decades of the twentieth century.

Long committed to the preservation of its rich past, the Lawnside Historical Society centered its activities on the Peter Mott House. Built in 1845 and believed to have been used to harbor people fleeing slavery, by the early twenty-first century it survived as the oldest building in Lawnside. Opened to the public as a museum in 2001 after activists saved it from demolition, the Peter Mott House demonstrated Lawnside’s deep regard for its history and close community ties.

Jason Romisher is a Canadian historian whose M.A. thesis, “Youth Activism and the Black Freedom Struggle in Lawnside, New Jersey,” explores the topics of African American high school student activism and Black power in a self-governing African American community. He is working on a research project about Helen Hiett, an American scholar, journalist, and Second World War correspondent. He holds degrees from Simon Fraser University (M.A., 2018), Lakehead University (B.Ed., 2002), and Queen’s University (B.A. Honours, 2001). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University