Lotteries

Essay

Lotteries have a long and controversial history in the Philadelphia region. Since the early eighteenth century, random drawings of numbers have funded charities and clubs, paid for roads and schools, settled estates, distributed land, and promoted various private and state-run initiatives. Lotteries have drawn multitudes of customers seeking cash and other prizes, but over three centuries they have cycled between widespread acceptance and outright prohibition. The economist Adam Smith (1723–90) viewed lotteries as a destructive “tax on ignorance,” while Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) saw them as a beneficial “voluntary tax.” This ambivalence reflected both the difficulties of regulation and underlying class, race, and ethnic discord. In the Philadelphia region, Quakers led the earliest and most effective crusades against public, or government-sanctioned, lotteries.

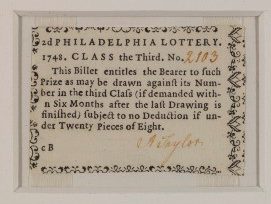

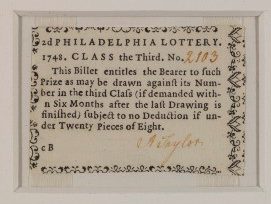

Early colonists relied heavily on lotteries to raise revenue in a way that did not involve direct governmental intervention. Seventeenth-century joint-stock ventures such as the Virginia Company introduced English practices and attitudes about the lottery to North America, luring settlers with promises of riches. William Penn (1644–1718) did not fund his colony with similar schemes, but lotteries soon became a hub of Pennsylvania’s economy. In 1720, the American Weekly Mercury advertised Philadelphia’s first known drawing; the prize was a house at Third and Arch Streets. Private lotteries—neither endorsed nor outlawed by the assembly—financed the city’s infrastructure of roads, bridges, market houses, and wharves. Printers were well positioned to benefit from consumers’ growing appetite for chance. Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) advertised drawings, printed tickets, and organized lotteries to distribute land, fund associations such as fire companies, and establish a militia in 1747. Such lotteries were quasi-official: corporation and commonwealth authorities frequently served as lottery managers, selecting spaces such as the courthouse for public drawings.

After 1740, political turnover, the introduction of games from neighboring colonies, and demographic shifts expanded the lottery’s influence in the region. Reflecting a religious aversion to games of chance, Quakers wielded their waning influence in the colonial assembly to ban private lotteries in 1762, following decades of attempts. The ban had little effect. Quakers lacked the power to ensure its enforcement, especially as entrepreneurs from Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland flooded the local market with games to fund the Seven Years’ War. Nearby Petty’s Island attracted lottery managers, whose broadsides promising property, jewelry, artwork, and cash prizes drew mixed crowds of Philadelphians. Within the city itself, taverns, coffeehouses, and peddlers also did a brisk business selling tickets for these so-termed “foreign” schemes. Lax regulations and proximity to Philadelphia made Delaware the mid-Atlantic hub of the colonial lottery trade, drawing customers (“adventurers”) as eminent as George Washington (1732–99), whose signed lottery tickets became sought-after ephemera. In the colonial interior, meanwhile, immigrants introduced and managed their own games of chance, as German-language lottery advertisements show.

Lotteries After Independence

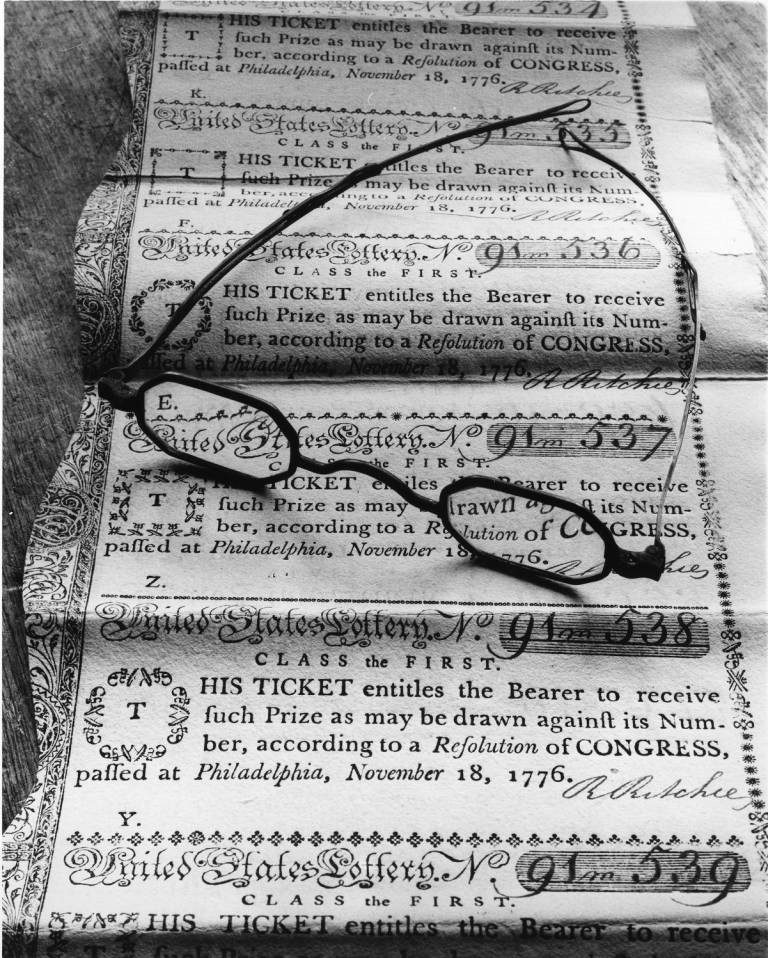

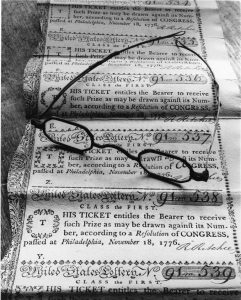

The work of building a new nation justified a new wave of lotteries after independence. Congress authorized the United States Lottery in November 1776 to raise $1.5 million for the war effort. It was to be held in four drawings, or classes, but mismanagement, poor distribution of tickets, and currency depreciation forced managers to postpone the first class and cancel the rest. By its conclusion in May 1778, the lottery had grossed only $100,000 for the government. The failed experiment at a national lottery did not discourage the founding generation from using lotteries to build a more unified nation. As postwar economic conditions improved, local elites prevailed on state lawmakers to formally sanction lotteries by passing charters. From 1796 to 1808, the Pennsylvania legislature chartered seventy-eight schemes, mostly to expand the state’s nascent transportation system. Delaware and New Jersey chartered several lotteries for colleges and courthouses. State charters typically contracted a small cadre of local elites to manage, and derive income from, schemes. Framing their work as a public good, managers adorned tickets and broadsides with images of national progress: schools, churches, roads, bridges, and canals.

Despite these overt claims to the commonweal, a series of controversies starting in 1811 contributed to the public’s growing perception that lotteries were less about civic initiative and more about profiteering. In 1811, Pennsylvania lawmakers chartered the Union Canal Lottery to raise $340,000 to revive a moribund canal project linking the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Rivers. Between 1811 and 1833, the lottery distributed $33 million in prizes but raised only $124,000, prompting allegations of waste and corruption by its managers, which included Henry Yates (1770–1854) and Archibald McIntyre (1772–1858) of New York. Using new marketing tactics, the firm of Yates & McIntyre helped to transform the lottery from a local enterprise to a national one after 1820. With networks of ticket brokers along the eastern seaboard, Yates & McIntyre and other lottery managers expanded the availability of foreign, or out-of-state, schemes. Moreover, by introducing the sale of half, quarter, and even one-sixteenth shares in tickets, managers drew more adventurers from Philadelphia’s laboring classes.

As lottery offices thronged the city’s streetscape in the mid-1820s, Philadelphia’s Quaker reformers spearheaded an anti-lottery crusade that spread into a national abolition movement in the 1830s. In 1817, the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Public Economy became the first local reform association to single out lotteries as sources of vice and poverty among the urban poor. By the late 1820s, anti-vice reformers and workingmen’s parties developed sharper moral and political-economic critiques. Their efforts, coupled with lawmakers’ embarrassment over the Union Canal boondoggle, set off a series of inquiries and litigation. In 1833, Governor George Wolf (1777–1840) signed an act abolishing lottery charters. Yet the statewide ban meant little if foreign tickets circulated widely. Led by a young Quaker lawyer, Job Roberts Tyson (1803–58), the Pennsylvania Society for the Suppression of Lotteries (established in 1834) corresponded with anti-lottery activists in other cities, published pamphlets and articles, and hosted lectures to drum up support for anti-lottery laws across the country. By 1860, only three states still chartered lotteries. Delaware, where the Wilmington brokerage firm Wood, Eddy & Company survived legislative challenges in the 1850s, was one of them.

Church Raffles and Gift Concerts

The Civil War rolled back many of these legislative victories. Delaware- and Kentucky-based firms maintained ticket offices in the region throughout the war. As the war dragged on, Philadelphia joined other cities in organizing church raffles, gift concerts, and other drawings to raise funds for injured soldiers and other causes. After the war, many southern and western states chartered lotteries to build or rebuild towns and roads. The largest and most controversial was the Louisiana State Lottery, granted a twenty-five-year state charter in 1868. Its innovative advertising and use of federal mails made the lottery ubiquitous in the Mid-Atlantic and across the country. By the late 1870s, the Louisiana Lottery sold 90 percent of its tickets out-of-state. Its concealed printing press in Delaware ensured a steady supply of tickets in the region. As court cases and controversies mounted, the federal government stepped in, outlawing the use of the mail for lotteries in 1890 and banning all shipments of lottery tickets and advertisements in 1895.

The effective abolition of state gaming did not stem popular interest in lotteries. During the nineteenth century, a culture of informal gaming loosely based on lotteries thrived in cities such as Philadelphia, particularly among immigrants and African Americans. Job Tyson and other antebellum observers noted the popularity of policy games, a type of side bet wherein people purchased “insurance” in the event certain numbers were not called. After abolition in 1890, clandestine lotteries became integral urban leisure outlets. Authorities were unable or unwilling to curb underground lotteries due to political pressure, police bribes, and challenges in identifying and prosecuting operators. Philadelphia’s criminal syndicates operated imported lotteries such as the Havana Lottery, French National Lottery, and Irish Sweepstake; photos of police raids in the 1930s and 1940s document their sophistication and popularity. In the 1920s, African American entrepreneurs in Philadelphia and other northern cities developed the numbers game, offering customers the ability to choose their own numbers and gamble small sums daily.

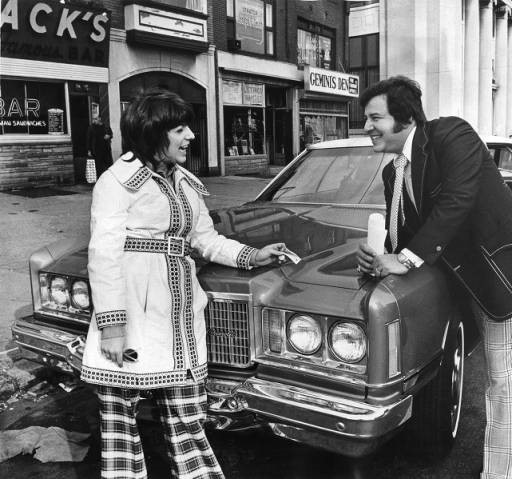

Several factors led to state lotteries’ resurgence after 1950. Fiscal emergencies spurred debates about reauthorizing state and federal schemes during the Great Depression and World War II. Moreover, public support for government-operated lotteries remained robust. New Jersey was one of the first states to legalize bingo (1954), a precursor to lotteries’ reintroduction in New Hampshire in 1964. In 1969, 81 percent of New Jersey voters supported a state lottery, which began in 1971. In August 1971, state lawmakers authorized the Pennsylvania Lottery to provide property tax relief for seniors, ending the state’s 138-year-long abolition of lotteries. Lotteries resumed in Delaware in 1974. Fraud remained an issue despite stronger oversight. In the 1980s “Triple Six Fix,” seven Pennsylvania Lottery officials weighted balls to ensure only certain numbers were drawn. Pervasive advertising and the advent of new games such as instant (scratch-off) lotteries in the 1970s and multistate Powerball in the 1980s fueled the industry’s growth as a national confederation of state lotteries. In 1991, Pennsylvania Lottery historical ticket sales surpassed $15 billion. In an era of backlash against income and corporate taxes, mid-Atlantic states relied more on lotteries to fund education, health, and transportation programs after 2000.

With its social diversity, tradition of reform, and cluster of states with robust lotteries, the greater Philadelphia region has had a unique relationship with lotteries. Many of the features that distinguished it in the early colonial period continued to do so in the twenty-first century. Critics still claimed lotteries preyed on the poor, promoted illegality, and were inefficient. Advertisers played on the same dreams of instant and life-altering wealth as they did in 1750, and media publicized stories of people winning a fortune and then losing it all. Finally, both state-run and informal lotteries remained entrenched in the local economy and leisure culture of greater Philadelphia, as the ubiquity of roadside “Lotto” signs attested.

Robert Gamble is a lecturer of history at the University of Kansas. He researches the history of regulation, capitalism, and urban space and has published articles on the antebellum secondhand trade and colonial peddlers in the Mid-Atlantic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Why privatize the New Jersey Lottery? (WHYY, April 29, 2013)

- NJ lottery tickets could soon be in the mail (WHYY, March 16, 2015)

- Lottery sales to debut at Pennsylvania liquor stores (WHYY, August 10, 2016)

- Delaware Lottery faces $2 million lawsuit after Keno glitch (WHYY, November 29, 2016)

- Governor Christie's final budget calls for using Lottery funds for pensions (WHYY, March 1, 2017)

- Can the New Jersey Lottery save the pension fund? (WHYY, April 3, 2017)