Mother’s Day

Essay

First rising to popularity in Philadelphia, Mother’s Day has been formally observed on the second Sunday in May since 1914 and celebrated in the United States for even longer. Serving various purposes since the late nineteenth century, Mother’s Day has deep connections to religion, war, feminism, and consumerism. For over a century, the meaning and purpose of Mother’s Day has been used and contested to celebrate individual mothers, enfranchise women, boost congregation numbers, and sell goods, among other purposes.

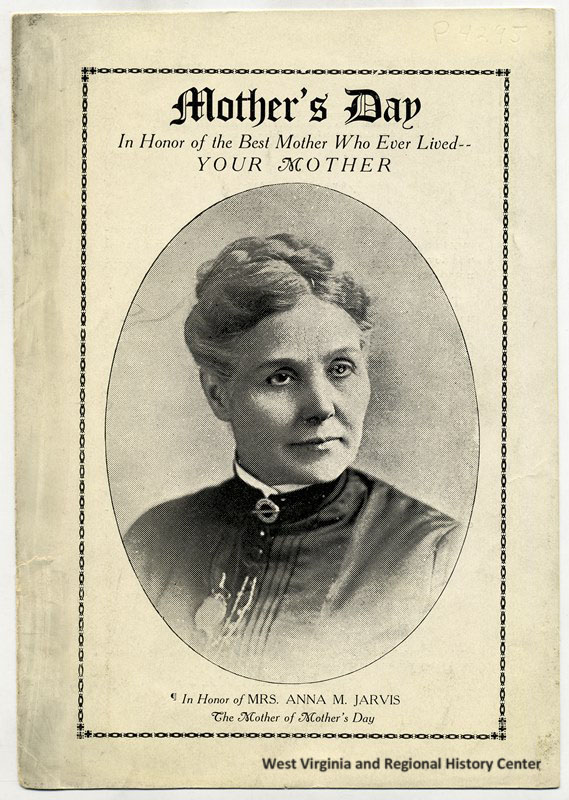

The formal celebration of Mother’s Day in the United States is often attributed to Anna Jarvis (1864-1948), a Philadelphia woman determined to commemorate her own mother with a national observance. However, Jarvis was not the first woman to propose a holiday honoring mothers, nor the first woman to engage Philadelphia society in the holiday’s celebration. In 1870, thirty years before Jarvis’s campaign, Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) founded Women’s Journal, a weekly publication in Boston, and featured her Mother’s Day Proclamation that same year. An activist, Howe intended to use Mother’s Day as a call to women to promote peace both in their homes and politically in the wake of the American Civil War, which had permanently separated so many mothers from their children. In 1872, Howe called for Mother’s Day to be celebrated on June 2, and between 1873 and 1913 several American cities held annual services on that day. In Philadelphia, the Universal Peace Union (UPU), a group dedicated to ending war and eradicating the American military, faithfully celebrated Howe’s holiday for four decades. Records of the UPU’s commemorations were kept and published in the organization’s magazines, The Voice of Peace and The Peacemaker and Court of Arbitration.

Despite its relatively positive reception, Howe’s holiday did not reach widespread audiences and her call for an end to war was, for many, too radical. Initially, many UPU members believed women’s equality was crucial to securing world peace, but by the turn of the twentieth century the group shifted focus and downplayed the political role of mothers, encouraging instead cooperation and collaboration between male and female activists. By 1906, the UPU was sponsoring the celebration of “Peace Day” in the Philadelphia school system. By Howe’s death in 1910 the politically active, women-led peace movement she had begun evolved into a new kind of Mother’s Day, influenced and spearheaded by Philadelphian Anna Jarvis.

Anna Jarvis’s Mother’s Day

Jarvis, born in West Virginia, was the tenth child of Granville and Ann Jarvis and their first daughter to live past infancy. She moved to Philadelphia with her brother when she was twenty-eight years old and became an editor at Fidelity Life Insurance Company. When her mother’s health began to decline, Jarvis moved her to Philadelphia and cared for her until her death on May 9, 1905. Jarvis went into a long period of mourning that lasted more than two years and culminated in her newly imagined Mother’s Day observance in 1908.

Jarvis envisioned the day as a way to honor and commemorate her “unselfish Christian mother,” who gave all for her children. Jarvis’s Mother’s Day differed from Howe’s substantially, as Jarvis advocated that individuals “honor the mother of their own heart” and pay no mind to women’s work beyond motherhood. Using her business connections in Philadelphia, Jarvis put together a wealthy group of supporters to sit on a Mother’s Day Committee. Members included department store owner John Wanamaker (1838-1922) and food-processing magnate H.J. Heinz (1844-1919). By 1908, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that many in the city were observing Mother’s Day.

Jarvis, who never married or became a mother, committed most of her time to the Mother’s Day cause, writing letters to state and federal legislators and beseeching Congress to declare the holiday official. Although many supported the idea of Mother’s Day, legislators were not keen to vote on the issue. One called the subject “not suitable for legislation,” while others wittily suggested a “mother-in-law’s day.” It was not until Jarvis had the backing of the Protestant Sunday School movement that her holiday garnered major attention and observation.

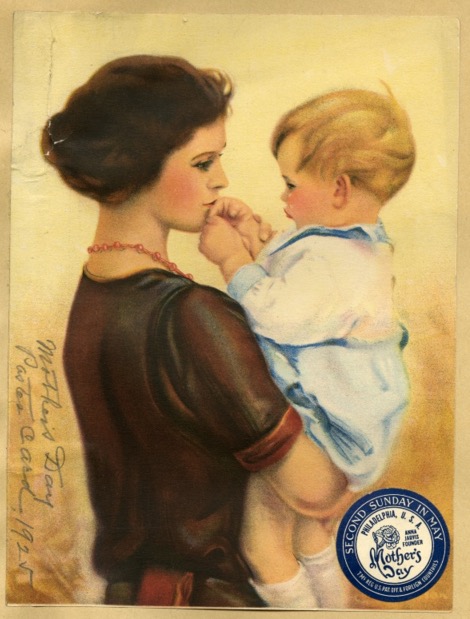

In an effort to publicize Mother’s Day, Anna Jarvis reached out to George W. Bailey (1840-1916), a chairman of the executive committee of the World’s Sunday School Association. Bailey saw potential in a church-led celebration of Mother’s Day, and in 1910 the association endorsed the holiday. Sunday school participation on Mother’s Day was a logical next step for Bailey and his colleagues, as children enjoyed celebrating special occasions and their mothers highly approved of themed lessons on appreciation and respect for parents. As churches embraced Mother’s Day they saw Sunday School attendance rise, and according to a May 1913 issue of the Presbyterian Advance, the high turnout could help ministers “reach the unchurched and the occasional church-attendant.” The popularity of Mother’s Day grew quickly, and in 1914 President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) officially proclaimed the second Sunday in May as Mother’s Day.

Changing Meanings

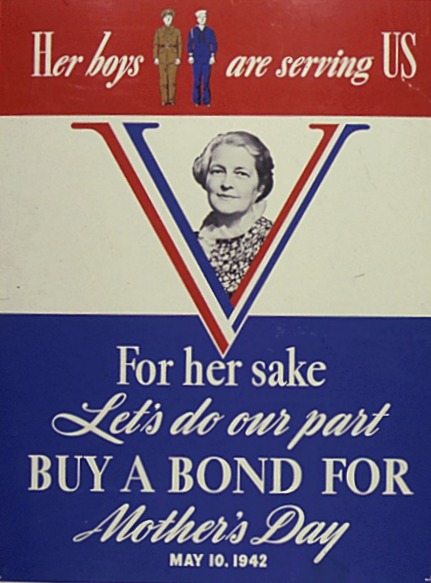

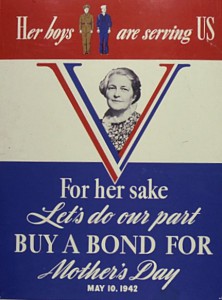

In the decade following 1914, Mother’s Day was widely celebrated, participation increased each year, and Jarvis was heralded as “the founder of Mother’s Day” in newspapers and advertisements across the county. During this decade, businesses began using the holiday for marketing purposes. In 1913, John Wanamaker’s department store became one of the first businesses to host a Mother’s Day celebration that included music and flowers for customers. In 1916, an advertisement for Snellenburg’s department store in Philadelphia suggested purchasing mother a Victrola, made in neighboring Camden, New Jersey, and greeting card. Printers, florists, chocolatiers and others soon followed suit and began to sell goods for Mother’s Day. During the First World War, Mother’s Day celebrations highlighted connections between motherhood, war, and women’s political and patriotic duties. On Mother’s Day 1918, General John Pershing (1860-1948) requested that all soldiers take a moment to write letters to their mothers. That same year, President Wilson commended American mothers for offering their sons to the United States military, echoing Howe’s sentiments that mothers sacrifice the most in times of war.

Initially, Jarvis was on good terms with businesses that pushed the Mother’s Day message, especially in the early years when her movement lacked support. However, over subsequent decades as more companies used and, in Jarvis’s view, abused the message of Mother’s Day, Jarvis fought to reclaim her holiday’s meaning by writing letters, taking out ads, and copyrighting the phrase “Mother’s Day.” She also objected to the way that the American War Mothers, formed in 1917, used Mother’s Day to fund-raise and further their own cause. Jarvis became so incensed by the societal changes to Mother’s Day that in 1933 she wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) to beseech him to remove the holiday from the nation’s official calendar.

Modern Traditions

Jarvis spent the last years of her life in Marshall Square Sanitarium in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where she died in 1948. Despite rampant commercialization, in the twenty-first century the holiday she promoted remained a day for putting mothers first and appreciating their hard work and sacrifice. Internationally, many countries adopted the American holiday over the course of the twentieth century and many others hold their own celebrations of women and motherhood (for example, Mothering Sunday in Great Britain and International Women’s Day in many former Communist countries). In Philadelphia and the surrounding region, groups and businesses offered traditional celebrations such as Mother’s Day tea, brunch, dinners, church picnics, and shopping and spa trips.Activist events, such as feminist political lectures, mother-daughter martial arts classes, and even demonstrations on behalf of women’s health have also taken place. The mid-May celebration also corresponded with some of the first outdoor events of the year, including the Azalea Festival in Hamilton Township, New Jersey, and outdoor music festivals in Atlantic City and Wildwood, New Jersey.

The annual celebration of Mother’s Day in Philadelphia and the United States can be understood as a holiday with complex meanings. Though not entirely true to Jarvis’s vision, or Howe’s for that matter, the holiday has reflected changing attitudes toward motherhood, femininity, domesticity, religion, and patriotism, while still holding fast to the celebration of motherly love and sacrifice.

Mikaela Maria is an editorial, research, and digital publishing assistant for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. She recently received her M.A. from Rutgers University and works as a public historian and museum professional in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History