Pennsylvania Hall

Essay

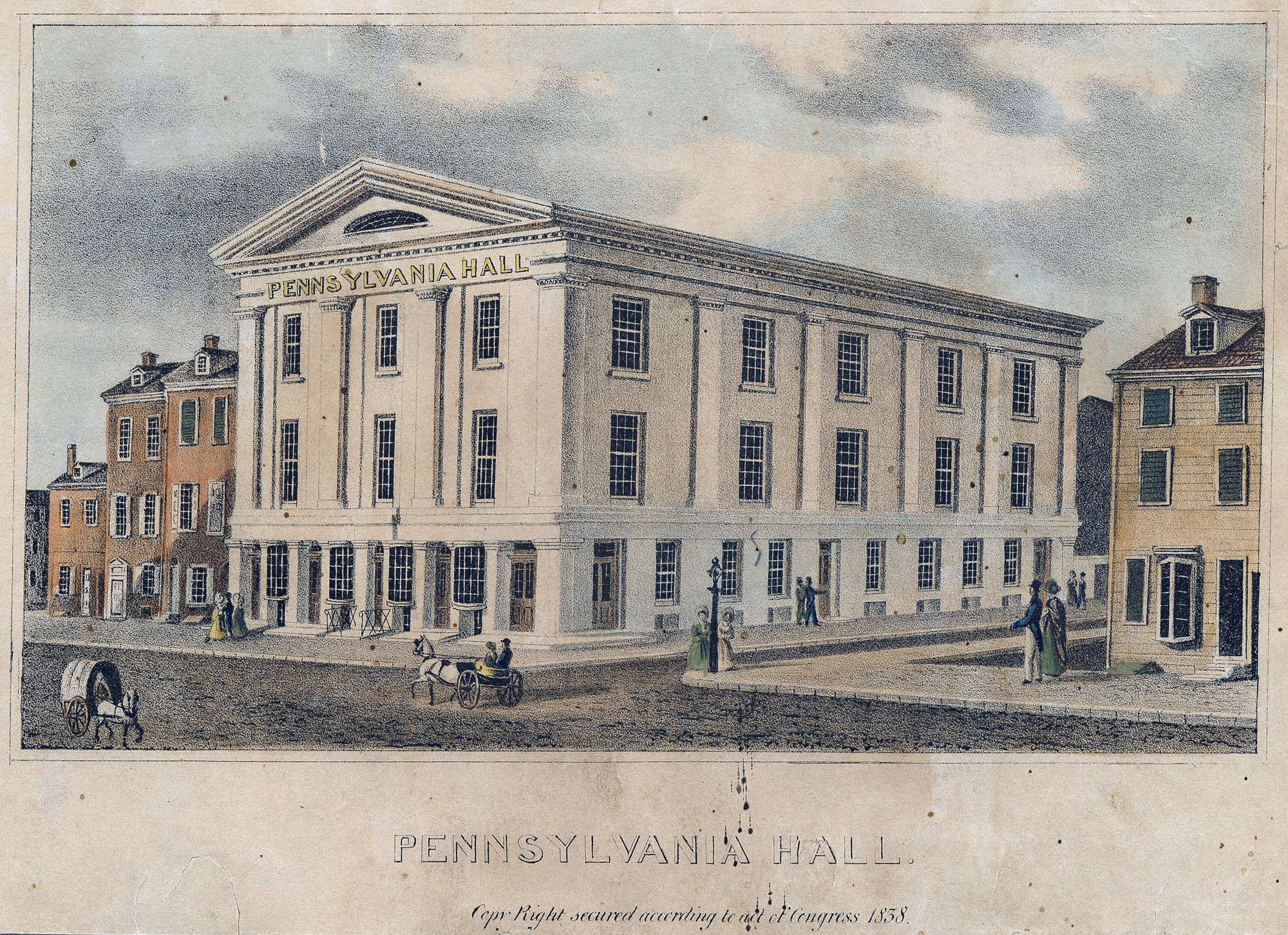

Pennsylvania gained a reputation as the birthplace of American abolition soon after the American Revolution, but that status caused unrest as debates over slavery grew contentious in the antebellum years. The tension led to a number of riots, one of the most notable being the 1838 destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, a meeting place for antislavery groups on Sixth Street about two blocks north of Independence Hall.

The riot at Pennsylvania Hall occurred at a time of backlash against abolitionism, despite its long history in the region. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS), the nation’s first and best-known antislavery group, helped secure Pennsylvania’s gradual abolition law, the nation’s first, in 1780. In 1794 abolitionist allies from New York, Delaware, and New Jersey had joined efforts with the PAS to form the American Convention of Abolition Societies, which met a number of times between 1794 and 1829, four times in Philadelphia. The group held its final meeting in Philadelphia in 1837, a pivotal year that saw the end of that organization but the beginning of the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society (PASS), whose members sought immediate rather than gradual abolition of slavery. When abolitionist women and men started the process of bringing this more aggressive type of antislavery to the greater Philadelphia area by forming the Philadelphia Female Antislavery Society (PFASS) in 1833 and the Philadelphia Antislavery Society in 1834, many PAS members not only welcomed but joined the new organizations.

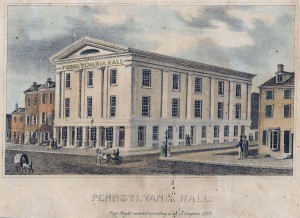

Soon, however, the rise of immediate abolition agitation, combined with the success of the PAS, created a backlash that resulted in churches and meetinghouses refusing to rent facilities for antislavery gatherings. Gradual and immediate abolitionists in Philadelphia then joined forces to form the Pennsylvania Hall Association, to raise money for and oversee construction of a very large and modern meeting hall at Sixth and Haines Streets (between Arch and Race Streets). PFASS members played a large role in raising funds to build the hall, collecting roughly $40,000 within a year. Many members of the Pennsylvania Hall Association were local white Quakers affiliated with one or more of the region’s antislavery groups. Black antislavery leaders in the antislavery community also played important roles in fundraising and in overseeing construction, which began in 1837 and ended in time for a grand opening celebration beginning on May 14, 1838.

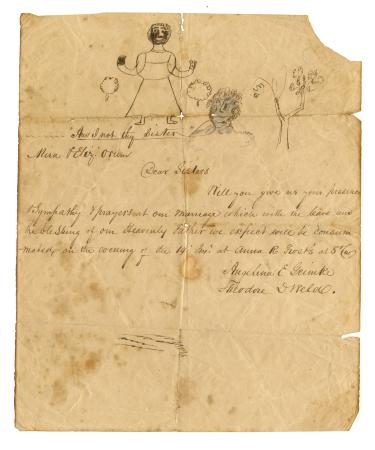

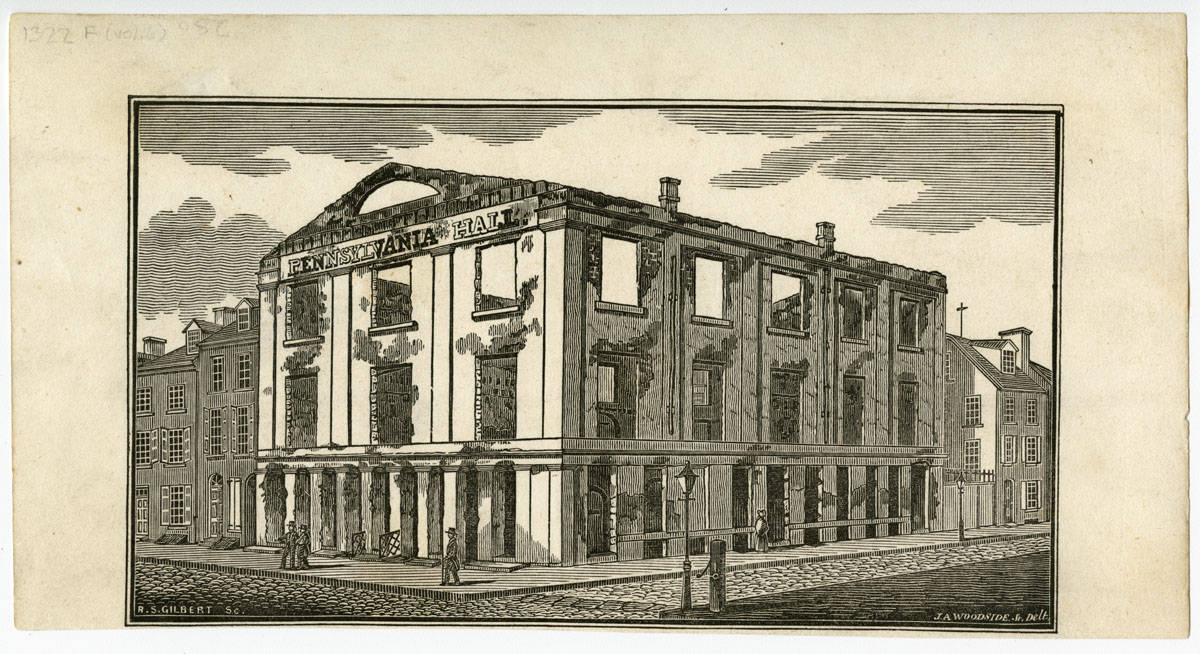

During its brief existence—three days from start of the grand opening to its destruction—Pennsylvania Hall housed the offices of the eastern district of the PASS, a free produce store, an antislavery reading room, the antislavery Pennsylvania Freeman newspaper, several meeting rooms, two large lecture rooms, and a large hall known as the “Grand Saloon.” The Association celebrated the hall’s opening by inviting abolitionists from all over the northeastern United States to attend a multiple-day ceremony that included meetings of the PASS, the Philadelphia Lyceum, and the Antislavery Convention of American Women.

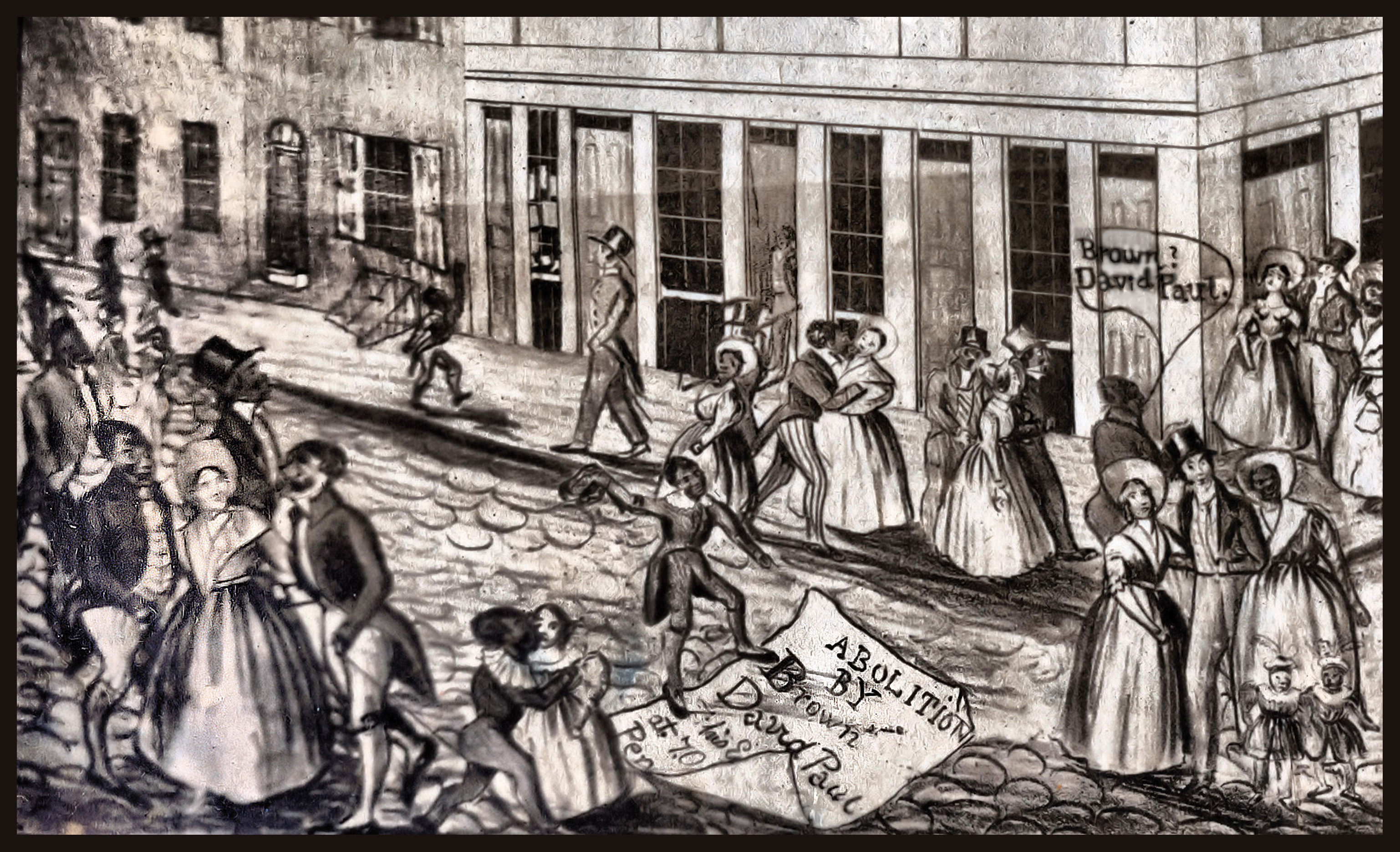

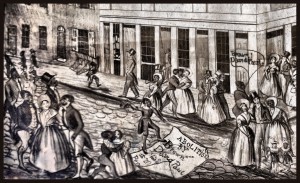

Resistance to the hall and what it symbolized emerged immediately, and ended with one of Philadelphia’s most famous acts of riot and destruction. As the abolitionists gathered, onlookers–already resentful of the abolitionists whom they blamed for the growing black population in the city and the resulting job competition–spread rumors of racial “amalgamation” and inappropriate behavior at the hall.

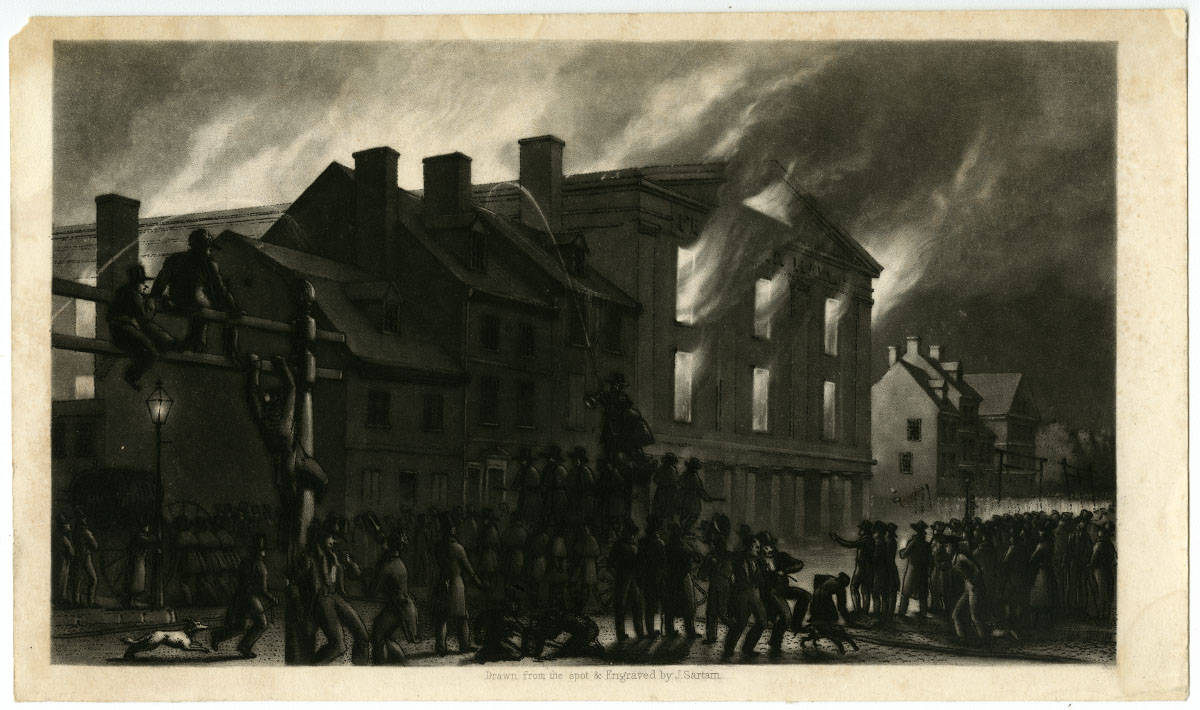

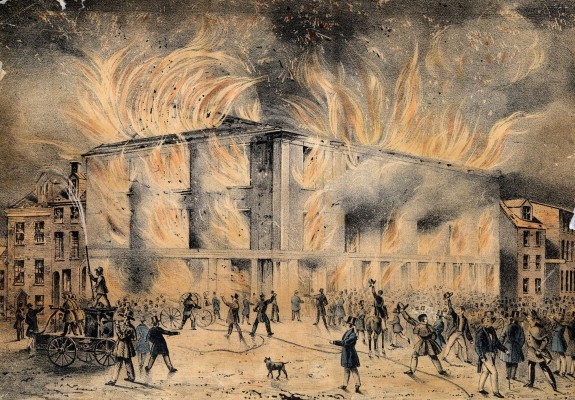

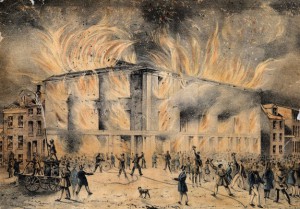

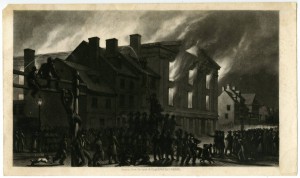

Crowds formed around the building immediately upon its opening, and on the third day of the conference, when women inside the hall began to speak about the horrors of slavery, before an audience that included black and white men and women, the crowd outside began to throw bricks through the windows. Despite half-hearted efforts by Mayor John Swift (1790-1873) to disperse the crowd, the attack escalated on May 17, 1838. A group later identified as dock workers broke down the doors, allowing a diverse white mob to enter the hall and set a number of fires, fueling them by the gas that was piped in for lighting. Sheriff John G. Watmough (1793-1861) gathered about a dozen of the troublemakers, but was prevented by the crowd from maintaining custody. By the end of the night Pennsylvania Hall was a smoldering shell.

During the following decade the abolitionists unsuccessfully sought justice in the court system. No one was convicted of the crime, though dozens were arrested, and five men were investigated for their role in the incident. Finally, in 1847, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court declared the county responsible for damages, and the Pennsylvania Hall Association received $27,942.27.

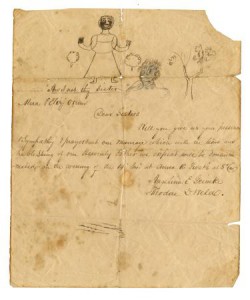

Though the hall stood for only a short time, it had an important and lasting effect on the regional and national antislavery movements. People who had previously ignored abolitionists, or expressed irritation at them for “agitating” and endangering the Union, began to reconsider their stance in light of this obvious attack upon free speech. Abolitionists took advantage of this opportunity to argue that those who denied black freedom also sought to hamper white freedom. The women contributed to this endeavor by marketing a variety of goods made of wood from Pennsylvania Hall.

In the end, the hall offered a graphic symbol of the struggle for both black and white freedom, and a reminder of the power of proslavery forces in the United States. Abolitionists were able to use this symbol to portray their cause as a defensive movement for freedom and to tout the proslavery position as a danger to white as well as black liberty.

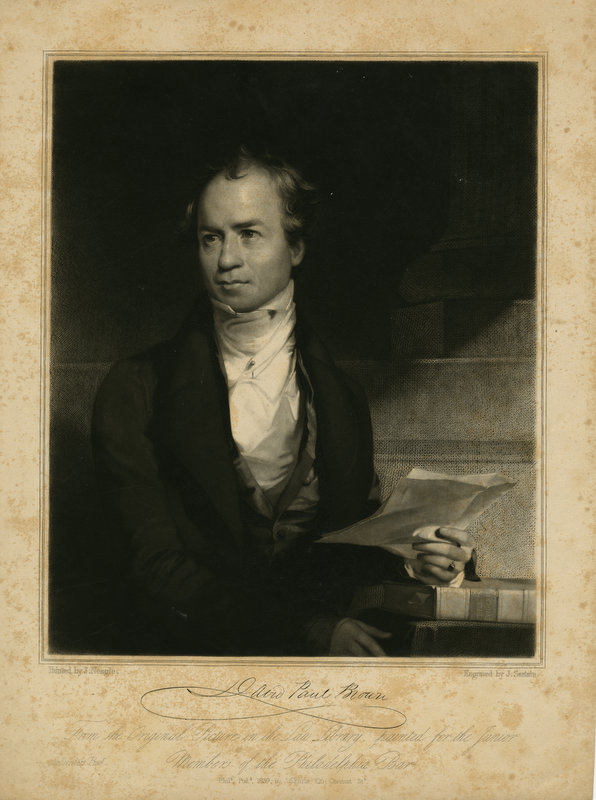

Beverly C. Tomek is the author of Pennsylvania Hall: A ‘Legal Lynching’ in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (NYU Press, 2011). She earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Houston and teaches at the University of Houston-Victoria.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

National History Day Resources

- Constitution of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, published with An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in Pennsylvania, 1787 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Proceedings of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, 1838 (Internet Archive)

- Newspaper Article: Destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, The Columbia Democrat, May 26, 1838 (Library of Congress)

- Review of the report of the Committee on Police to the Concils of Philadelphia in relation to the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall, 1838 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- 5th Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, 1839 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)