Philadelphia Maritime Exchange

Essay

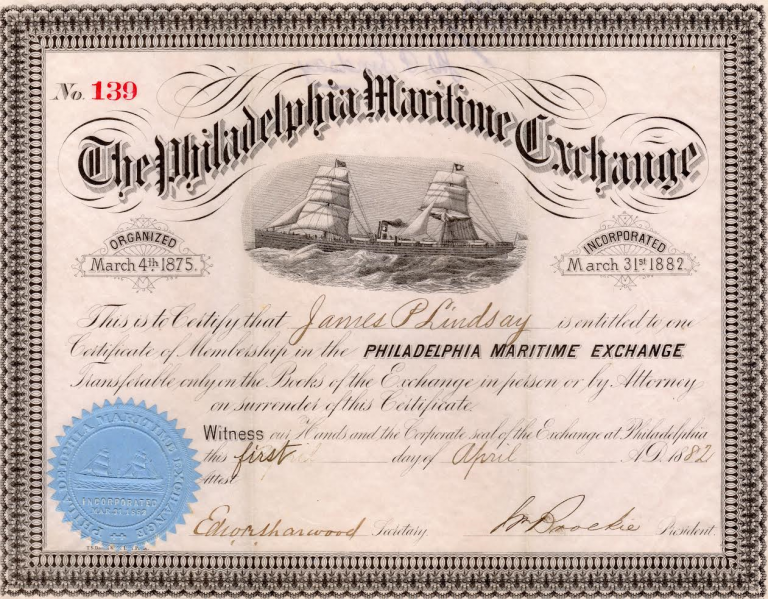

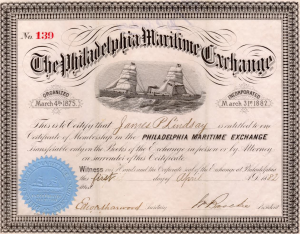

In 1875, a group of influential maritime and business leaders who recognized the importance of the Port of Philadelphia’s standing with respect to other North American ports formed the Philadelphia Maritime Exchange. The goal of the exchange was to position Philadelphia as a premier port in North America by increasing the city’s direct trade with foreign countries and ensuring that the Delaware River ports would offer quick turnaround and better ship handling. From these beginnings, the exchange played an active role in the port’s growth and served the Delaware River maritime community into the twenty-first century.

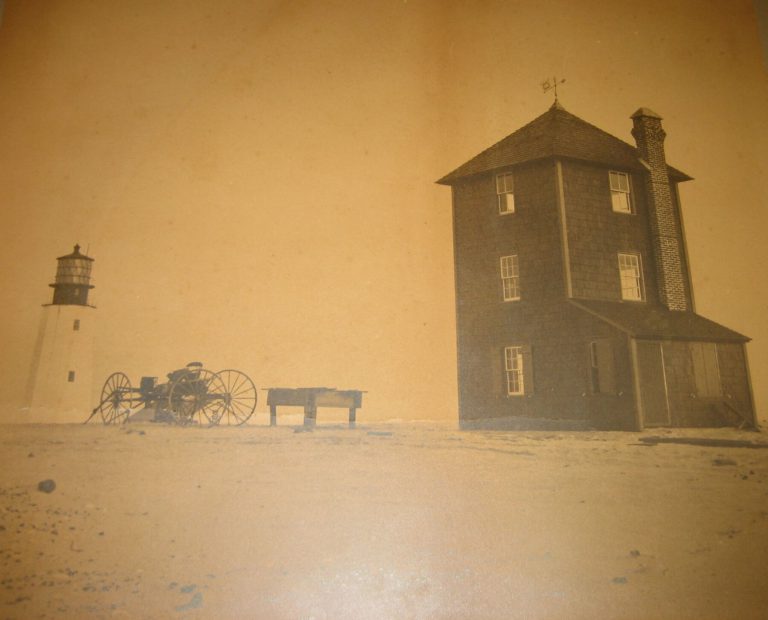

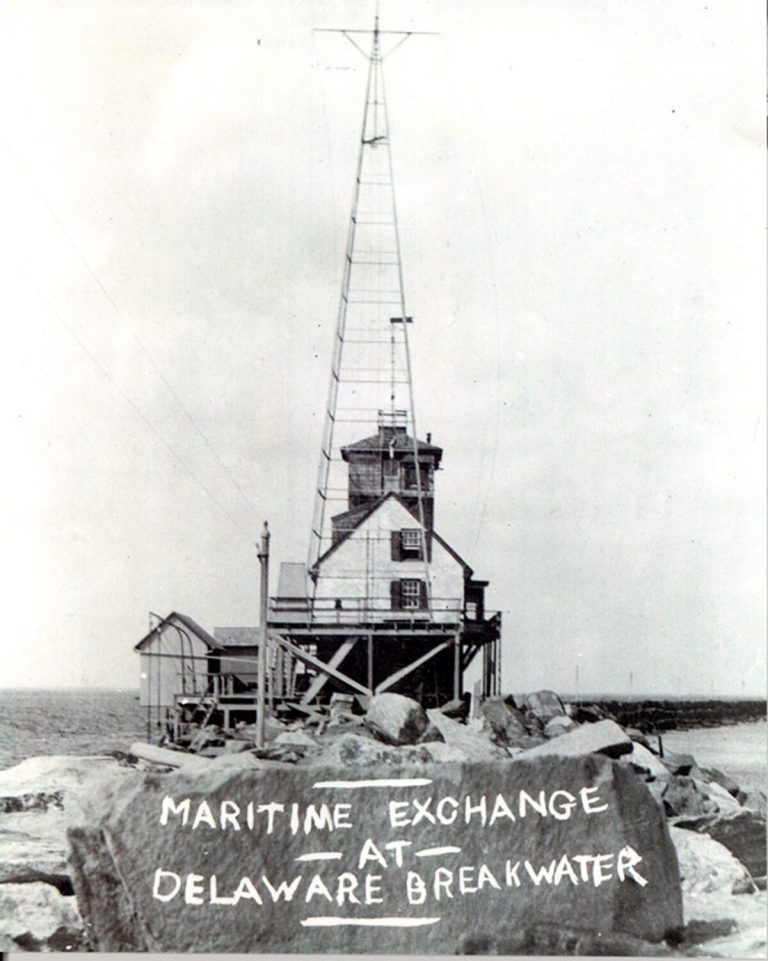

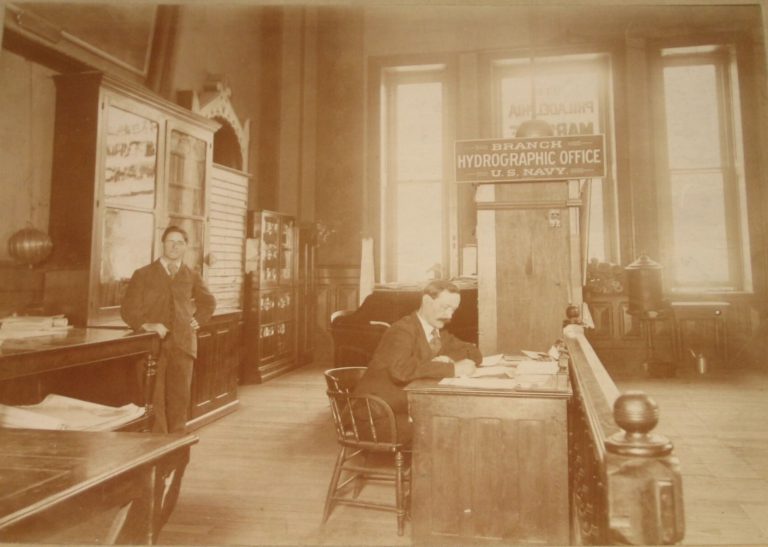

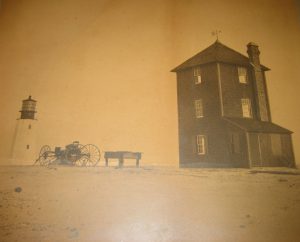

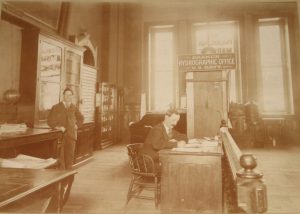

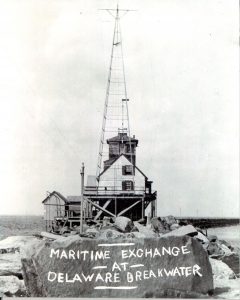

By the time of the exchange’s founding, the Port of Philadelphia had long been a key aspect of the region’s economic life. By 1750 Philadelphia had surpassed Boston as the largest city and busiest port in North America and held that position until it was eclipsed by New York in 1825. During the post-Civil War era, as Philadelphia became an industrial giant and a key hub for commercial trade, demands on the port reached new levels with the rise of iron, steel, coal, and oil production, along with the increasing use of the railroad to transport these materials. To improve efficiency, the exchange built reporting stations along the Delaware to track ship arrivals. The observation stations reported to a central point in the city and from there the information was distributed to any party concerned with the ship while it was in port.

The exchange took an increasingly active role in proposing and instituting rules and regulations governing local shipping after April 29, 1882, when the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted it a perpetual charter to “acquire, preserve, and disseminate all maritime and other business information, and do such other and lawful acts as will tend to promote and encourage trade and commerce of the Port of Philadelphia.” In 1887, the exchange issued its first eighteen Maritime Rules, covering points on which disputes tended to arise, such as ways of determining the readiness of ships or methods for handling hazardous cargo. These and other regulatory actions became the model for many U.S. ports as well as the foundation of international shipping governance.

At the time the exchange was formed, the Port of Philadelphia consistently handled three principal commodities: grain, sugar, and petroleum. The exchange formulated and approved standard practice for the carriage of these goods and became one of the first to adopt forms of charters for specific commodities or trades. These charters defined issues such as the loading, unloading, and discharge of vessels; how many days a ship was allowed in port (lay days) and the port charges resulting from overstay (demurrage); and rules regulating the delivery and receipt of special cargoes. In most ports these were matters decided by Boards of Trade, Chambers of Commerce, merchants, or combinations of the respective groups. In Philadelphia the advent of the Maritime Exchange streamlined the process.

To assure that the Port of Philadelphia would remain competitive, the exchange also played a role in the development of the Delaware River, the Schuylkill River, and the harbor. Over time, advances in ship design, construction, and operation created the need for the port to accommodate deeper drafts and longer ships. From 1885 through 1938 the exchange promoted actions such as the removal of Smith’s and Windmill islands from the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Camden and projects to widen and deepen the channel. Similarly, the exchange maintained and improved the Schuylkill River, the main tributary to the Delaware River and a key channel for moving commodities from the interior of the country to the port.

The interests and actions of Philadelphia Maritime Exchange always reached beyond the water to related issues such as the railroad transportation of commodities, quarantine of goods and immigrants on land, immigration, outbreaks of yellow fever, and civic affairs. The exchange actively promoted technological advancements such as electricity and telephones that required cables across the river and were key advocates for establishing bridges across the Delaware River in response to population growth in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Over the years, it supported humanitarian aid to foreign countries, endorsed state legislation such as the “Pure Stream Bill” to assure water quality, and opposed the sale or charter of government-owned vessels to foreign countries.

By the late 1980s, the exchange became the primary advocate for all segments of the tristate port industry after a sister organization, the Joint Executive Committee for the Improvement of the Harbor of Philadelphia and the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, closed its doors. In keeping with its broadened geographic scope, the activities of the exchange expanded to more extensive connections to legislators, regulators, policymakers, and other industry members concerned with international transportation matters including trade and quota issues, maritime security, automation, safety, environment, and dredging.

The increase in scope of the exchange led to a name change in the 1990s to the Maritime Exchange for the Delaware River & Bay. The exchange’s mission, however, remained focused on promoting and encouraging commerce and international trade while working closely with public port organizations on issues with impact on the port and related businesses. Maintained by membership dues collected from merchants, importers, ship owners, tug and lighter operators, suppliers, and others connected with the maritime trade of the lower Delaware River, by 2016 the exchange had a membership more than 275 and remained the voice of safe, efficient, and cost-effective commerce on the Delaware River and Bay.

Terry L. Potter is the Director of the J. Welles Henderson Archives & Library at the Independence Seaport Museum. She holds a Master’s Degree in American History from Rutgers University, Camden.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University