Philadelphia Pepper Pot

Essay

Philadelphia pepper pot, a spicy stew-like dish comprised of tripe, other inexpensive cuts of meat, vegetables, and an abundance of spices and hot peppers, is related to the pepper pot soup of the Caribbean region. By the early nineteenth century, the dish had developed characteristics making it uniquely Philadelphian. Philadelphia pepper pot became popular throughout the country before declining in the early twenty-first century. Although it disappeared from most store shelves and menus, pepper pot could still be found in select restaurants in the Philadelphia area.

Pepper pot (also known as “pepperpot” or “pepper-pot”) came to the Philadelphia area in the mid-eighteenth century from the West Indies region of the Caribbean, at that time connected with the city through trade. A hybrid of Spanish and West African food traditions, pepper pot originated in two versions, one based in cassareep, a sweet and sour syrup derived from the bitter and poisonous cassava, and the other using callaloo, a dish made from greens that originated in West Africa. Edward “Ned” Ward (1667-1731), an English satirist who visited Jamaica in the late seventeenth century, wrote that after eating just a few spoonfuls, all he wanted was “a drop of water to cool [his] tongue.”

Most likely, enslaved Africans brought an indigenous version of pepper pot based on callaloo to Philadelphia in the mid-eighteenth century. Like many Native American, African, and European dishes, especially among the poorer classes, pepper pot was a communal dish. Dishes of this type had no specific recipe, only general guidelines to follow—meat, vegetables, and other available ingredients slowly cooked in one pot and typically eaten with bread. According to tradition the remnants from one day’s meal became the basis for the next, resulting in a dish that could last for decades or even a century.

“West-India Pepper Pot”

By the late eighteenth century, pepper pot had become well known in the American colonies. A recipe for “A West-India Pepper Pot,” clearly indicating the popular belief about the dish’s origins, appeared in the first cookbook produced in America for an American audience, The New Art of Cookery, published in Philadelphia in 1792. The recipe called for a variety of meat, including veal, mutton, ham, and beef; vegetables including onions, carrots, celery, leeks, turnips, and greens; simple dumplings made of flour and water; and spices including all-spice, cloves, and mace. One of the last steps was to “season it very hot with Cayan pepper and salt,” emphasizing the heat associated with the dish.

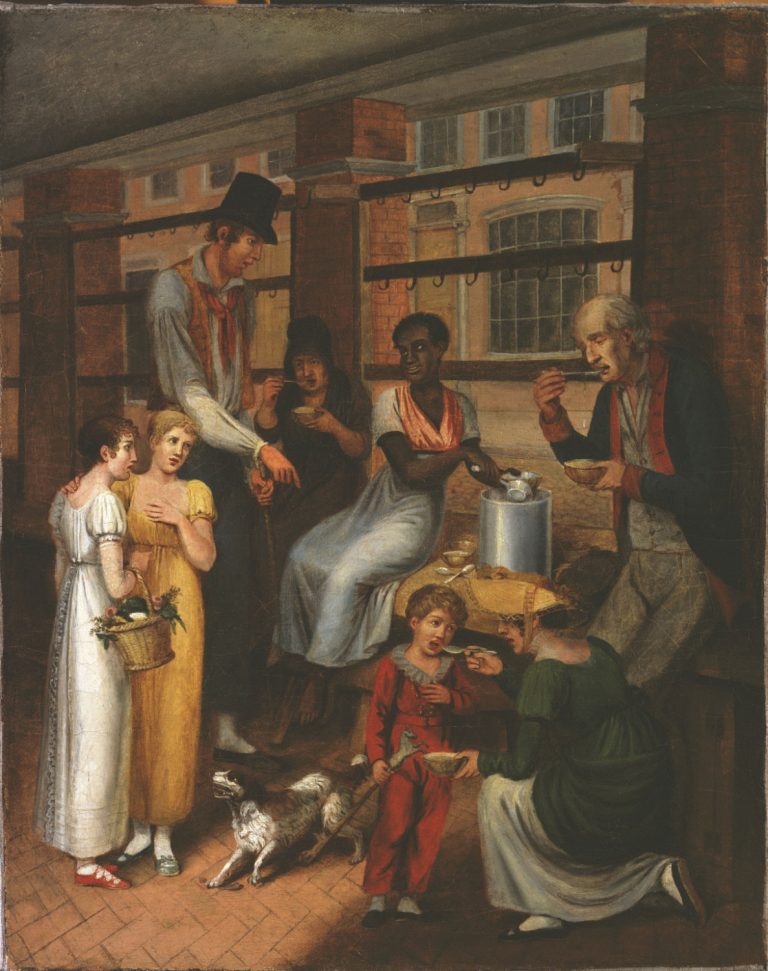

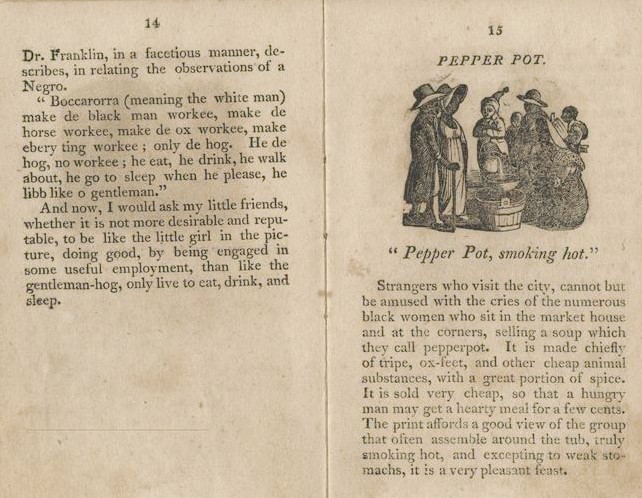

Pepper pot became more prominent and characteristic of Philadelphia by the early nineteenth century. The Cries of Philadelphia, published in 1810, included a wood-cut illustration titled “Pepper Pot, smoking hot,” and described the “numerous black women” who sold a “pleasant feast” of pepper pot “made chiefly of tripe, ox-feet, and other cheap animal substances, with a great portion of spice” in markets and on street corners. In 1811, a similar scene titled Pepper-Pot was exhibited at the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts by John Lewis Krimmel (1786-1821), an early American genre painter. The painting shows an African American woman selling pepper pot to a diverse group of customers. Created during a period when Philadelphia had one of the largest free black populations in the country, these images documented black women’s work as entrepreneurial street vendors, an alternative to domestic work when options for employment were limited.

Philadelphia pepper pot became well known throughout the country. By the late nineteenth century, advertisements for restaurants serving “Philadelphia” pepper pot as well as recipes appeared throughout Pennsylvania, the Midwest, New Orleans, and Hawaii. One recipe noted that the cook could add “any other herb or vegetable your taste demands,” much like earlier versions. An account written in 1894 by a New Yorker visiting Philadelphia described pepper pot as a regional dish unique to Philadelphia, much like scrapple, and commented that anyone asking for it in other cities “would be looked upon as a candidate for an asylum.” In 1901, the Clover Club in Philadelphia advertised that pepper pot would be served on its Thanksgiving menu. A later article in San Francisco poked fun at the menu, noting “surely such a combination would never pass muster outside of Pennsylvania.”

Canned Soup

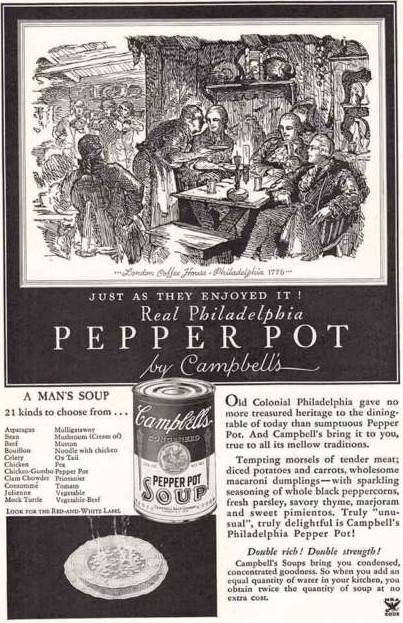

The first canned version of Philadelphia pepper pot appeared in the early twentieth century as one of the original soup offerings sold for 12 cents a can by Camden-based Campbell Soup Company. By 1927, Campbell’s advertised it as the same version “served at the favorite club of Philadelphia’s early Colonial aristocracy,” despite the dish’s origin as a street food.

Throughout the early twentieth century, Philadelphia pepper pot remained nationally popular. Restaurants advertised it as a special offering, newspapers published recipes, and cookbooks featured a variety of recipes, many including the traditional tripe. Although the dish dipped in popularity by the mid-twentieth century, it resurged around the United States’ bicentennial celebration in 1976 because of a supposed connection between pepper pot and the Revolutionary War. Legend had it, incorrectly, that pepper pot had been invented to nourish the troops at Valley Forge after their defeat by the British at the Battle of Germantown.

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Philadelphia pepper pot fell out of favor, although it continued to be made by home cooks. Many institutions that had served it as a staple dish, such as the Four Seasons Hotel and the Union League of Philadelphia, removed it from their menus. Campbell’s and Old Original Bookbinder’s, a food division created by a restaurant of the same name in Philadelphia to sell packaged versions of their soups, condiments, and sauces, also stopped selling canned pepper pot by 2018. Although Philadelphia pepper pot sometimes appeared as a special at restaurants, it could be found consistently in just a few locations, such as the colonial-themed, reconstructed City Tavern, which advertised it as West Indies Pepperpot Soup, “a spicy colonial classic,” and the specialty store Rieker’s Prime Meats.

Philadelphia pepper pot originated in the West Indies and migrated to Philadelphia with enslaved Africans, providing them and their free descendants with an inexpensive meal and a ware to sell in markets. For more than a century, Philadelphia pepper pot was a both a popular street food and a specialty dish at high-end restaurants.

Theresa Altieri Taplin earned an M.A. in history from Villanova University. She is a Certified Archivist and museum professional in Philadelphia.

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University