Pipelines

Essay

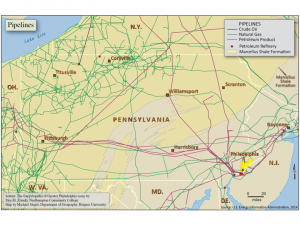

Reaching hundreds of miles to the Philadelphia area from western Pennsylvania, pipelines carrying oil and gas were critical to Philadelphia’s emergence as an industrial power and linked the fates of suppliers and consumers for more than 160 years. The development of the pipelines, marked by both challenge and innovation, supplied energy for residential and business consumption as well as commercial export. By the twenty-first century, distribution and transmission lines held the potential to boost the region’s role as an emerging energy hub.

Before long-distance pipelines, beginning in 1836, the first energy pipelines in Philadelphia carried manufactured gas within the city for lighting. The Philadelphia Gas Works, the first municipally-owned distribution company, illuminated Second Street with forty-six manufactured gas lights.

The discovery of an oil spring in Titusville, Pennsylvania, followed by the drilling of the first successful well in 1859, touched off an oil rush by speculators and presented urban dwellers with other energy options, especially for lighting. However, moving crude oil long distances was both expensive and dangerous. Teamsters transported crude oil in forty-two-gallon barrels by horse-drawn wagons, either to barges floating down the Allegheny River bound for Pittsburgh or onto the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad, bound for Philadelphia and New York. The movement of the barrels, together with evaporation, sloshed and spilled oil into the rivers and along the railways cutting deeply into profits. As little as 15 to 20 percent of the oil produced reached consumers.

Transporting oil even short distances was cost prohibitive as teamsters gouged drillers at $4 per barrel for transport, a cost more expensive than moving the entire rail freight to New York City. Consisting of as much as 6,000 wagons daily, the heavy hauls destroyed existing roads and made conditions especially dangerous by spilling slick oil on muddy roads and endangering both teamsters and the animals that bore the burden of the haul.

Demand for Kerosene Increases

As long as oil remained difficult to transport at acceptable cost, Philadelphia continued to rely on manufactured gas to supply homes and businesses, but crude oil byproducts like gasoline, Naptha, paraffin, and tar came to be used in factories to spur Philadelphia’s industrial development. Demand for kerosene increased in homes as well because it provided a bright, steady light that increased hours of productivity. Known for its safety, it replaced costly whale oil and foul-smelling and dangerously explosive camphene, a derivative of turpentine. One gallon of kerosene could produce 140 hours of safe, odorless illumination.

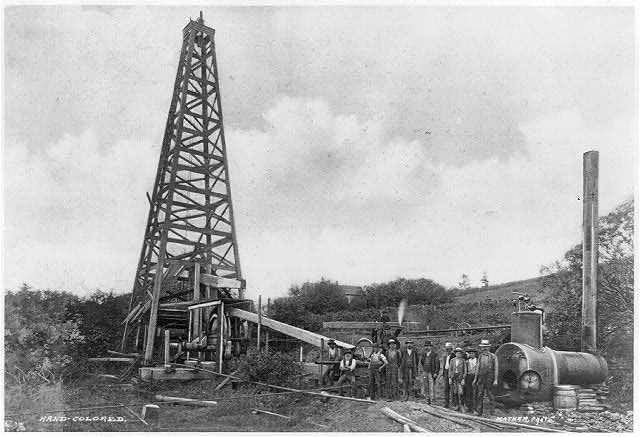

It was amid the Oil Rush that the first transmission pipelines were built by individual drillers as an experiment intended to move oil short distances, transporting it directly from the well to refineries up to a mile away. Rudimentary at best, these systems consisted of two boards nailed together in a “V” shape and covered with a third, allowing gravity to initiate the flow. These wooden distribution, or gathering lines proved to be fragile and brittle, and thus they were soon replaced with small-diameter cast-iron pipes. Threatened by the interference of the encroaching “experiments” with their control over hauling oil, teamsters responded quickly by tearing up the pipelines.

In 1865, Samuel Van Syckel (1813-94) pioneered the first successful long-distance transmission lines near Titusville, managing to overcome the teamster’s sabotage by posting guards along the five-mile route. Delivering approximately 2,000 barrels daily through a two-inch diameter wrought-iron pipe with the help of three pumps, the Van Syckel pipeline inspired a flurry of additional pipeline projects, resulting in construction of an expanding wrought-iron infrastructure from the oil fields to railroad terminals and canal entries.

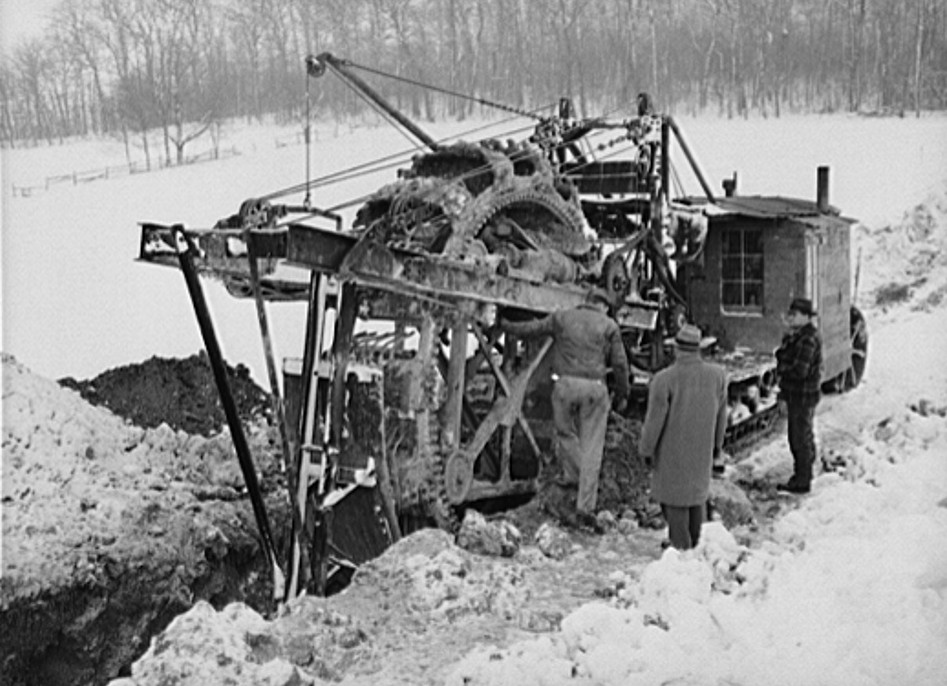

By the 1870s pipeline technology improved with the introduction of subsurface cast-iron pipes. Such large-scale pipelines required purchasing land rights from landowners along the pipeline route and, in many cases, required court orders to secure eminent domain or condemnation of properties along the route. The land needed to be cleared of trees and stumps, trenched and then, once the pipe was installed, filled-in again.

Pipelines Prone to Leaks

Once set, pipelines were prone to slow and steady leaks as well as explosion, which polluted water and destroyed land. The lines often cut through watersheds, streams, and wetlands, removing large swaths of trees to clear a path for construction.

Showing little regard for the environmental or human impact, speculators eagerly invested in infrastructure projects that promised cheap, abundant, and reliable sources of light and industrial fuel to supply the increasing demand of the Greater Philadelphia region and the European markets it served through export from its ports.

Byron D. Benson (1832-88) and several other producers organized the Tidewater Pipeline Company, Limited, in 1879, seeking to bypass the monopoly John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) had secured over area rail transport. Tidewater constructed a 109-mile, six-inch-diameter wrought-iron pipeline from Bradford to Williamsport capable of transporting 250 barrels per hour to ready tank cars on the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad bound for Philadelphia and New York.

The Tidewater Pipeline revolutionized oil transmission and distribution by allowing producers to stabilize cost fluctuations in transportation and to undermine Standard Oil’s monopoly of the railways. To strengthen Tidewater’s hold, Benson arranged to transport the daily flow of 6,000 barrels of crude via the Central Railroad to the Lombard & Ayers works in Bayonne, New Jersey, and the Logan & Farnsworth refinery in Philadelphia. The line was further extended to Tamanend, Pennsylvania, and, then, just short of the seaboard in Bayonne, New Jersey.

Standard Oil Builds Its Own Pipelines

Not deterred by the competition, Standard Oil responded by building its own pipelines towards its refineries in Ohio and along the Atlantic Coast, including port refineries in Philadelphia. The Cleveland line was completed in 1880, reducing shipping costs by more than half. The following year, Standard Oil built a four-inch line from Bradford to Buffalo, parallel to a competing six-inch line built by the Buffalo & Rock City Company. Rockefeller cut off Buffalo & Rock City’s supply chain by purchasing New York refineries and, without any buyers, Buffalo & Rock City was forced to sell out to Standard Oil.

Using right of ways purchased from the Erie Railroad, Standard Oil subsequently built a series of trunk pipelines to refineries toward the Atlantic Coast, starting with a six-inch pipe from Olean, New York, to Saddle River, New Jersey, in 1881 and co-locating another six-inch line that was extended to Bayonne.. The following year, the company built a 260-mile pipeline from Colegrove, Pennsylvania, to supply refineries at Gibson’s Point owned by Philadelphia’s Atlantic Refining Company. In 1883, the line was expanded by seventy miles to Baltimore refineries.

By 1882, Rockefeller controlled 3,000 miles of pipelines. He accelerated construction by introducing steam-powered machinery to trench, lay, and thread pipes, saving manual labor for cutting, stumping, and removing trees or boulders.

After negotiations failed to prevent Standard Oil from acquiring Tidewater Pipeline, the Pennsylvania legislature prohibited the merger in 1883. Notwithstanding the prohibition, the two companies entered a pooling agreement, allowing Standard Oil to gain control of Tidewater and maintain a dominant share of transmission facilities.

Oil Lines as Public Utilities

Following damaging revelations of Rockefeller’s monopoly by pioneer muckracking journalist, Ida Tarbell (1857–1944) in 1902, Congress and the courts dealt Standard a number of blows. In 1906, the Hepburn Act made oil transmission lines public utilities by requiring interstate pipelines to offer services at equal costs to all shippers and designating these transmission lines as common carriers subject to the regulation of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

In 1911, the Supreme Court ruled that Rockefeller’s tactics violated the Sherman Antitrust Act and broke the Standard Oil Trust into 34 separate companies. The following year the court drew on the Sherman Antitrust Act again to order Standard Oil of New Jersey to dissolve into seven regional oil companies. Finally, in 1913, Congress made the first attempt at federal involvement in U.S. pipeline ratemaking by granting the ICC authority over valuation of common carrier lines.

Establishing transmission lines as common carriers and breaking up Standard’s monopoly opened the oil market, and the flow of crude oil from producing regions to the Greater Philadelphia area increased, making petroleum a viable option for lighting, heating and fuel. The introduction of Edison’s electric lightbulb and mass production of automobiles hastened the shift from kerosene lamp oil to gasoline by reducing the domestic kerosene market. In 1911, U.S. output of gasoline overtook kerosene. In response to these innovations, crude oil pipelines carried oil from prolific fields in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas to the refineries on the East Coast, creating the beginning of what would be a national network of transmission and gathering lines.

Demand for petroleum products in the Philadelphia area increased in the two world wars in the first part of the twentieth century. During World War II, German submarines threatened American tankers delivering and exporting petroleum products from the East Coast, sinking forty-six oil tankers. In response, the U.S. government contracted with the Delaware-based War Emergency Pipelines Corporation (WEP), a conglomeration of eleven private oil companies to initiate construction on the Big Inch and Little Big Inch pipelines (1942-43) from the Gulf Coast to refineries and distribution centers in New York and Philadelphia. They transported approximately 350 million barrels of crude oil by the end of the war.

Postwar Pipeline Conversions

Following the war, Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation (TETCO) converted pipelines to transport natural gas as part of a deal with WEP. In 1957, the Little Big Inch converted to a common carrier of petroleum products, supplying Philadelphia refineries and encouraging local markets to convert from manufactured to natural gas. Additional natural gas transmission pipelines serving the Greater Philadelphia region included the Williams Transcontinental Gas Pipeline, commissioned in 1950, extending 10,500 miles from Texas through Pennsylvania to markets in Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, D.C. The Columbia Gas Transmission Line provided service from the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic Coast, connecting to the Millennium Pipeline near Port Jervis, New York, and then to Downingtown, Pennsylvania, extending eastward under the Delaware River into New Jersey.

The discovery in 2008 of up to 500 trillion cubic tons of recoverable natural gas in the Marcellus Shale Formation, stretching through north, central, and western Pennsylvania, opened a new era by stimulating a flurry of natural gas pipeline projects terminating in Philadelphia. Analysts estimated that as many as 4,600 miles of new interstate transmission lines would be added to the region by 2018.

Such activity spurred opposition from environmental groups, who disputed the safety of large- volume distribution through densely populated residential areas, watersheds, and fragile ecosystems. Because of the high risk of explosion, these groups called for more stringent regulation on pipeline construction. Fearing cumulative impacts, including the potential for water pollution, fragmentation of forests, and destruction of ecosystems extending from natural gas extraction, environmentalists called for moratoriums and even a state-wide ban in Pennsylvania.

The Marcellus Revolution

Touted as the Marcellus Revolution, the flow of abundant and low-cost natural gas prompted a dramatic increase in the number of gas-fired generation facilities, shifting the source of energy generated by the power grid from coal and nuclear fusion to natural gas. While demand for oil and gas remained high through the winter heating, gas-fired energy powering air conditioners and cooling systems increased consumption of natural gas through the summer months.

The shift toward natural gas was exemplified by Philadelphia Gas Works’ announcement in June 2014 that it would add twenty-four natural gas vehicles to its service fleet. The first public natural gas filling station opened off of U.S. Route 1 in Philadelphia’s East Falls neighborhood in September 2014.

Philadelphia’s proximity to the Marcellus Shale made the city a potentially ideal energy hub for shipping, trading and refining natural gas. To realize those possibilities, investors sought to take advantage of the existing infrastructure—pipelines, refineries, storage facilities, and ports, while expanding gas-fired power plants and overhauling antiquated distribution lines, thus hastening the transition from coal and oil to natural gas.

Other pipeline expansion projects sought approval by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Spectra Energy’s proposed Greater Philadelphia Expansion Project and the proposed Mariner East 2 expansion project were projected for completion by 2016. PennEast Pipeline had respective target dates of 2018 and 2017, pending final FERC approval. Sunoco Logistics planned to revitalize the Marcus Hook Refinery with the approved Mariner East 2 expansion project. Together, these lines would serve consumers in the Greater Philadelphia region and beyond.

From the first oil well drilled in Titusville, Pennsylvania, to the massive pipeline expansion anticipating Philadelphia’s emergence as an energy hub, the Greater Philadelphia region has benefited from pipelines transmitting petroleum products from the Pennyslvania hinterlands to light and heat homes, power industry and manufacturing, and boost local economy.

Tara M. Zrinski teaches Philosophy at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. She has been one of four eco-feminist bloggers writing for From the Ground Up, a blog on Shalereporter.com. Her work has focused on documenting the impacts of Marcellus Shale development on the environment and human health as well as the environmentalist response to natural gas extraction, pipeline construction, and energy transition in Pennsylvania.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- U.S., Pa. measures address pipeline safety (WHYY, December 15, 2011)

- New pipeline will carry natural gas liquids across state to Delaware County refinery (WHYY, December 16, 2013)

- Report: PGW second-worst for gas pipeline leaks (WHYY, March 28, 2014)

- New 100-mile natural-gas pipeline proposed for Pennsylvania and New Jersey (WHYY, August 20, 2014)

- Feds approve Leidy Southeast pipelines in New Jersey (WHYY, December 19, 2014)

- Federal data: As oil production soars, so do pipeline leaks (WHYY, May 25, 2015)

- South Jersey Gas pipeline plan still fueling dispute, despite Pinelands Commission OK (WHYY, October 19, 2015)

- Opponents to the PennEast pipeline register in large numbers for FERC hearing (WHYY, November 3, 2015)

- Revised PennEast pipeline faces 2 month delay (WHYY, November 10, 2016)

- A common cause; from Standing Rock to Sweet Water, New Jersey's Pilgrim Pipeline (WHYY, January 31, 2017)

- Environmental group appeals New Jersey gas pipeline approval (WHYY, April 10, 2017)