Rocky

By Laura Holzman | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

More than just a popular series of Hollywood films or the fictional prizefighter whose life and career they chronicle, Rocky is a late-twentieth-century cultural phenomenon that reframed Philadelphia for local, national, and international audiences.

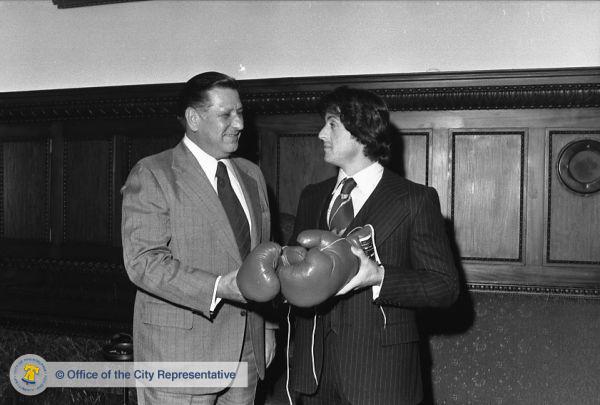

Rocky premiered in 1976. Written by and starring Sylvester Stallone (b. 1946), the film introduced audiences to Rocky Balboa: a down-and-out boxer and debt collector from Philadelphia who gained confidence as he trained to fight the reigning heavyweight champion. Although nearly everyone in Rocky’s world recognized that he was outmatched and expected him to lose badly, he held his own in a fight that lasted fifteen long rounds.

Fictional heavyweight Rocky Balboa had analogues in several actual boxers who fought during the twentieth century. Balboa shared his first name with Rocky Marciano (1923-69), the undefeated heavyweight champion from the 1950s. Chuck Wepner (b. 1939), who famously endured fifteen rounds in a 1975 match against heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali (b. 1942), was later dubbed “the real Rocky.” Also like Rocky, Philadelphia-based heavyweight champion Joe Frazier (1944-2011) was hailed as a hardworking blue-collar counterpart to his great rival Ali in the early 1970s.

Rocky, a low-budget production, won Academy Awards for Best Picture, Directing, and Film Editing. A franchise emerged. Rocky II (1979), Rocky III (1982), Rocky IV (1985), Rocky V (1990), and Rocky Balboa (2006) tracked the eponymous protagonist as he persevered in the face of professional and personal challenges.

Primarily set in Philadelphia, with many scenes filmed around the city, Rocky and each subsequent installment in the series (except Rocky IV) offered viewers both an imagined and an actual image of Philadelphia.

Spotlight on the City

Local viewers could take pride in seeing their city on screen, while audiences elsewhere could survey Philadelphia as they watched Rocky run past the Navy Yard, along the Schuylkill River, through the Italian Market, and down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Other sites that appeared throughout the films, including Laurel Hill Cemetery, Rittenhouse Square, and Broad Street near City Hall, marked the setting as Philadelphia. Even the unglamorous row houses and shops in Rocky’s urban neighborhoods of Kensington and, later, South Philadelphia, represented the residential city. As the cityscape changed over the course of three decades of Rocky films, the movies documented that transformation.

In addition to their role as a backdrop to the film, some sites, like the steps in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, actively contributed to Rocky’s story.

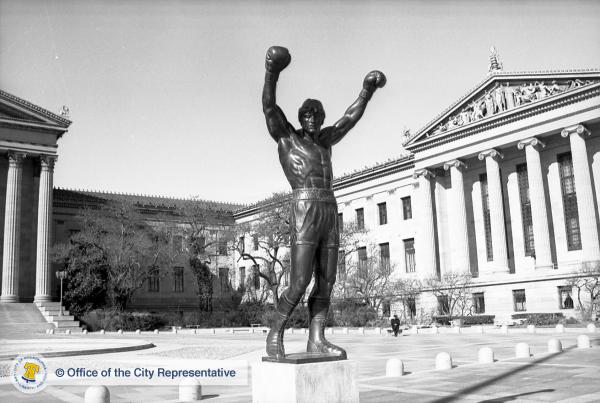

The climax of Rocky occurred during a training montage when Rocky triumphantly bolted up the seventy-two steps that lead from the Benjamin Franklin Parkway to the neoclassical façade of the Museum of Art. Rocky’s physical ascent demonstrated how his self-esteem had grown throughout the film. When he arrived at the top, he gazed out at the Philadelphia skyline; on his way to becoming a nationally recognized boxing star, Rocky appeared to hold the entire city in his vision.

The scene’s symbolism depended, too, on the museum’s cultural significance. Rocky’s journey from working-class Kensington to a recognizable bastion of high culture foreshadowed the wealth and cultural clout that the boxer earned as his career progressed.

Rocky-Philadelphia Overlap

The narrative of Rocky also overlaps with narratives about Philadelphia, its spirit, and its reputation. Rocky’s ability to beat the odds and transform from an average “bum from the neighborhood” into a nationally and internationally successful boxer corresponded to Philadelphia’s own arc during the late twentieth century. No longer the manufacturing power that it was decades earlier, and suffering from woes related to crime and political corruption, 1970s Philadelphia, like Rocky, was down and out. Rocky’s gritty perseverance became symbolic of the spirit of the city, suggesting that actual Philadelphians could similarly succeed in the face of seemingly overwhelming challenges. Nationally published newspaper articles and locally generated publicity materials promoted this belief. As policy changes, economic shifts, and tourism initiatives began to revive Philadelphia in the 1990s, the city demonstrated that, like Rocky, it could improve its condition and reassert its national and international significance.

Rocky and Philadelphia developed a symbiotic relationship that blurred the lines between the world of the films and actual Philadelphia. Some critics expressed concern that the films’ version of Philadelphia framed the city through the eyes of a white working-class protagonist beginning at a time when racial tensions in the city ran particularly high. Even so, Rocky’s fictional experiences and the image of the city that grew out of the early films resonated across diverse audiences.

Running up the steps of the Museum of Art became a popular tourist activity and a recurring trope in each Rocky movie. By the 1990s, the museum’s steps acquired a widespread vernacular title, “the Rocky Steps.” In addition to reenacting the popular scene from the film, runners understood their behavior as a performance that allowed them to channel Rocky’s perseverance.

In 1980, Stallone commissioned sculptor A. Thomas Schomberg (b. 1943) to create a bronze statue of Rocky. The 8-foot, six-inch piece appeared in Rocky III as the City of Philadelphia’s tribute to its by-then-famous hometown hero. Stallone donated the sculpture to the actual City of Philadelphia and proposed installing it in the same location where it appeared in the film. While critics rejected the sculpture on the ground that it was not worthy of display at the museum, supporters argued that embracing the statue would give deserved recognition to the Hollywood hit that generated valuable publicity and tourism for the city. The sculpture was moved several times over the next twenty-five years, but it spent much of that period on view outside the Spectrum arena in South Philadelphia. In 2006, the statue was permanently installed just north of the base of the Rocky Steps. There, it commemorates the character, the films, and their important reciprocal relationship with Philadelphia.

Laura Holzman is Assistant Professor of Art History and Museum Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Rocky Balboa's fictional South Philly house is up for sale (WHYY, March 16, 2013)

- Review: Broadway's 'Rocky,' but still Philly's fighter (WHYY, March 13, 2014)

- Proposal to redesign 'Rocky' steps would affect a city icon (WHYY, July 21, 2014)

- Sylvester Stallone Shoots 'Creed' in South Philly (NBC, February 17, 2015)