Train Derailments and Collisions

Essay

Since the earliest days of railroads, collisions and derailments have been a constant danger for both passengers and railroad workers. Large-scale disasters have been relatively rare in the Philadelphia region, despite its important role in railroad operation and development. However, news coverage, public outrage, and government intervention resulting from rail accidents around the country forced prominent companies such the Pennsylvania Railroad to adopt new safety technologies and regulations to ease public fears, restore efficiency, and increase daily traffic. Accidents highlighted failures or absences of railroad safety measures locally and across the United States.

Collisions and derailments occurred despite ongoing efforts to improve railroad safety. In the late nineteenth century, railroad companies sought to improve the durability of tracks by switching from iron to steel rails and to reduce accidents by building parallel tracks that allowed trains to pass each other. The Interstate Commerce Commission, created in 1887 to regulate transportation, issued a series of regulations requiring railroad companies to comply with safety regulations. Over time, new technologies such as Automatic Train Stop and eventually electric Automatic Train Control systems and in-cab signaling developed to forcibly stop trains if warning signals were ignored. However, many railroad companies hesitated to implement such costly equipment.

On early railroads of the nineteenth century, multiple trains traveled inbound and outbound on the same lines, making communication key to avoiding collisions and other track hazards. On a single-track road, a train would have to use a siding track off the main line to wait for another train to pass. Before the days of two-way radios, train crews had to rely on schedules, telegraphs at station stops, or simple line of sight in order to locate another train. These capricious methods were often vulnerable to a large degree of human error.

Great Train Wreck of 1856

Such was the case on July 17, 1856, in an event that came to be known as the Great Train Wreck of 1856. That day at the Cohocksink depot in the Kensington section of Philadelphia, a North Pennsylvania Railroad excursion train called the “Picnic Special,” carrying children from St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Sunday School, left the depot later than scheduled. Farther down the line at the Wissahickon station, the crew of the regularly scheduled train the Aramingo had no way of knowing that the Picnic Special was running late and so, after a brief period of waiting, pulled out of the station on the single-track line. The conductor intended to use a siding at Edge Hill to allow the Picnic Special to pass. However, the two trains collided around a blind curve by Camp Hill station, near the site of future Ambler, killing fifty-nine and injuring around one hundred. Immediately following the accident, Wissahickon resident Mary Johnson Ambler (1805-68) packed first-aid supplies and traveled the two miles from her home to care for the wounded. Years later, her heroics inspired the North Pennsylvania Railroad to rename the Wissahickon station as Ambler after her, and the town also took her name in 1888.

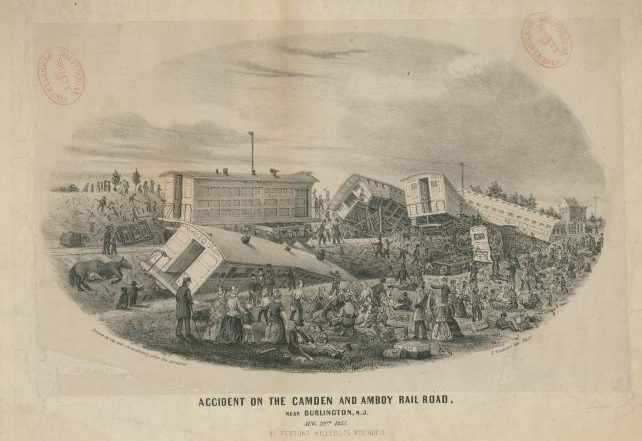

A similar incident had occurred in South Jersey on the Camden-Amboy Railroad on August 29, 1855. In this accident, two trains traveling in opposite directions on the single-track line between Philadelphia and New York spotted each other down the road near Burlington. The northbound train began to reverse. Down the line at a road crossing, a local doctor was driving his two-horse carriage, but windy weather caused dust clouds and made it difficult for both the brakemen and the doctor to see. The train struck the two horses and derailed four of the five train cars. This accident left twenty-one dead and sixty to one hundred wounded, although the doctor was unharmed. These accidents and subsequent derailments, among other highly publicized disasters nationally in the 1850s, aroused public outcry for increased railroad safety and highlighted the dangers of railroad travel in absence of safety measures.

Many railroads did not become double-tracked until traffic increased during and after the Civil War. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company planned its Main Line, connecting Philadelphia to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, to be double-track from its inception. However, the economic Panic of 1857 halted the double-track progress until the increased traffic of the Civil War made it necessary.

During the Civil War, as Union and Confederate forces used railroads heavily, railroad companies depended on poor quality British iron for tracks that quickly wore out and caused numerous derailments. After the war, railroads turned instead to steel as sturdier and better suited for newer, heavier cars and more powerful locomotives. By the late 1870s, the Independent Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad became one of the first American railroads to install steel rails along its main line. By 1914, Pennsylvania Railroad executives concerned with railroad productivity, more than passenger safety, also recognized broken rails to be a leading cause of derailments.

Automatic Train Stop Systems

Automatic Train Stop (ATS) systems, first patented by Pennsylvania Railroad workers in 1880, added an element of safety by preventing trains from passing restrictive signals. The initial system worked by dropping a bar on the train if it passed a stop signal. The bar would smash a glass cylinder on the locomotive, which would then release air pressure from the brake line and stop the train. In 1922, the Interstate Commerce Commission mandated that forty-nine major railroads implement ATS on at least one passenger division by 1926. However, ATS could not prevent derailments caused by speeding or stalling on a descent. This still remained in the hands of the engine man.

After excessive speed caused a train to derail in February 1947 near Gallitzin in central Pennsylvania, the ICC required all railroads to install cab signaling (in-cab displays corresponding with outside signal lights) or ATS where passenger trains exceeded 72 miles per hour. Finally, after an engine, Red Arrow, sped through a stop signal and collided with the rear end of the Philadelphia Night Express at Bryn Mawr on May 18, 1951, the Pennsylvania Railroad committed to installing cab signaling and Automatic Speed Control, or Automatic Train Control (ATC) as it came to be known. ATC uses electric pulses from the rails to apply the brakes on trains exceeding the speed limit. Similarly, on diesel and electric trains, “dead man” switches could stop the engine should the engineer become incapacitated.

One location, the Frankford Junction curve in Philadelphia, became the site of two accidents seventy-two years apart. On September 6, 1943, PRR’s Congressional Limited derailed as a result of loose equipment in the train’s under carriage. Due to its speed, the train could not respond to the signalman’s warning in time to stop. This accident left seventy-nine killed and 118 injured. Years later, on May 12, 2015, Amtrak train 188 entered the Frankford Junction curve at around 102 mph and flew off the tracks. The track had been recently equipped with Positive Train Control (PTC, a more advanced form of ATC), but it was not yet operational. Had PTC been active, the train’s excessive speed would have triggered the brakes upon passing a warning signal. Eight people were killed and more than two hundred were injured.

The absence of safety measures continued to be one of the leading causes of train derailments. Public outcry over accidents in the earlier, unregulated days of railroads precipitated the creation of safety innovations that protected and saved lives. With a large degree of railroad traffic, the greater Philadelphia region became a testing ground for these innovations. The decline in accident frequency demonstrated that with increased safety technologies, railroads could operate more efficiently and safely. Although train crews no longer operated blindly, in the absence of long-developed safety measures, the rails could still be a dangerous place.

Leonard Lederman earned his master’s degree in history at West Chester University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Major Train Derailments in Greater Philadelphia

November 8, 1833: Hightstown Rail Accident, Hightstown, New Jersey. An overheated journal box caught fire underneath one of the carriages on a Camden & Amboy train between Hightstown and Spotswood, New Jersey, causing an axle to break and derailing the train. The derailment killed one and injured twenty-three. Among the wounded was future New York Central railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877). Also on board the train was former president John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) who, in his journal, recorded the horror of witnessing the wounded victims. This derailment may have been the first fatal passenger train accident in U.S. history.

August 2, 1853: Sunset Cow Wreck, Bulls Island, Lambertville, New Jersey. At sunset, a Belvidere Delaware Railroad train struck a cow on the tracks. Six cars derailed, killing eleven.

August 29, 1855: Camden-Amboy Railroad Wreck, Burlington, New Jersey. Twenty-one people died and sixty to one hundred were injured after a train struck two horses pulling a carriage, causing four cars to derail.

July 17, 1856: Great Train Wreck of 1856, Ambler, Pennsylvania. A regularly scheduled North Pennsylvania Railroad passenger collided with a late excursion train, killing fifty-nine and injuring around one hundred.

October 4, 1877: Milford Wreck, Kimberton, Pennsylvania. Torrential rain from a large tropical storm caused the ground under the tracks near Kimberton to erode. A three-car Philadelphia and Reading Railroad train plunged into the thirty-foot chasm, killing seven.

September 19, 1890: Shoemakersville, Pennsylvania. After two coal trains collided and spilled timber and coal onto a passenger train track, a fast-moving Pottsville Express passenger train struck the coal debris and plunged into the Schuylkill River. Twenty-two people died and more than thirty were injured.

July 30, 1896: Atlantic City, New Jersey. A Reading Railroad Express train plowed into the side of Pennsylvania Railroad Red Men’s excursion train, killing around fifty and injuring over sixty.

December 3, 1903: Greenwood, Delaware. A winter snowstorm, resulting in decreased visibility, caused two trains to collide in the town of Greenwood. One train carried naphtha, a highly flammable liquid, which exploded with such force that Greenwood inhabitants reported glass shattered in almost every building in town. Only one brakeman and a nearby infant were killed, but the resulting fires wounded many and destroyed nine buildings, leaving locals homeless during the snowstorm. Firefighters could not respond until the following morning because the explosion had destroyed telegraph lines.

October 18, 1906: Atlantic City. Improperly placed tracks on a trestle bridge outside Atlantic City caused a West Jersey and Seashore Railroad train to derail, plunging several cars into the mud and water. Fifty died from drowning in the mud and rising water levels. A grand jury exonerated the elderly bridge tender but found the railroad company at fault for improperly placed tracks and a lack of mechanical warning signals.

November 27, 1912: “Sagging Bridge,” Glen Loch, Pennsylvania. The Cleveland Flyer train derailed as the result of a sagging bridge on the Pennsylvania Railroad line. Eight cars derailed, killing four and wounding forty-nine. Investigations found that a cover plate on the bridge had ruptured but could not determine the cause. Evidenced also showed that the train began to derail before it reached the bridge.

September 6, 1943: Frankford Junction, Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Railroad Congressional Limited derailed on the Frankford Junction curve as a result of loose equipment in the train’s undercarriage. Due to its speed, the train could not respond to the signalmen’s warning in time to stop. This accident left seventy-nine killed and 118 injured.

May 18, 1951: Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. A Pennsylvania Railroad train, Red Arrow, sped through a stop signal and collided with the rear end of the Philadelphia Night Express at Bryn Mawr, killing eleven and wounding fifty-seven.

December 26, 1961: York-Dauphin Station, Philadelphia. A four-car SEPTA subway on the Market-Frankford El line entered a curve just before the York-Dauphin station where it hit a guardrail causing the first three cars to derail. One man was killed and thirty-eight people were injured.

March 7, 1990: Philadelphia. Between 30th and 15th Street Stations, a dragging motor box caused a subway car to crash through a pillar, killing four and injuring 162.

May 12, 2015: Frankford Junction, Philadelphia. Amtrak train 188 entered the Frankford Junction curve at around 102 mph and flew off the tracks. The track had been recently equipped with Positive Train Control, but it was not yet operational. Had PTC been active, the train’s excessive speed would have triggered the brakes upon passing a warning signal. Eight people were killed and more than two hundred were injured.

April 3, 2016: Chester, Pennsylvania. A maintenance crew foreman neglected to confirm that dispatchers were routing trains around the work zone. As a result, an Amtrak train on the New York to Savannah line collided with a backhoe, killing two maintenance workers and injuring around forty passengers.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The Railroad in Pennsylvania (ExplorePAhistory.com)

- Mary Ambler (Ambler Main Street)

- How Wissahickon Became Ambler (Historical Society of Montgomery County)

- Tragic Train Wreck at 53rd Street and Baltimore Avenue (PhillyHistory.org)

- Is This the Train Tragedy We'll Learn From? (Hidden City)

- Camden and Amboy Railroad (Delaware River Heritage Trail)