Underground Railroad

By Beverly C. Tomek | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

With a deep abolitionist history and large and vibrant free Black population, Philadelphia and the surrounding region played a prominent role in the famed Underground Railroad. The loosely connected organization of white and Black people helped hide and guide enslaved people as they sought freedom in the North and Canada.

According to one of the earliest accounts, written by Robert Smedley in 1883, slaveholders began to use the term “Underground Railroad” in the late 1780s to describe clandestine efforts in the Columbia, Pennsylvania, area to help fugitives escape slavery. Columbia grew out of the small settlement of Wright’s Ferry, which was founded by Quakers and other white people who opposed slavery. Soon after its founding, the town gained a reputation for protecting fugitives and allowing free Black settlement.

Before long a system of escape routes led fugitives north from the Chesapeake toward Havre de Grace, Maryland, and across the Susquehanna River to Lancaster and Chester Counties. Several routes developed in south central and southeastern Pennsylvania and in southwestern New Jersey, regions with strong Quaker abolitionist networks and vibrant free Black communities that helped fugitives make their way farther north. Those traveling through New Jersey followed a route that later became the path of the New Jersey Turnpike. The southeastern Pennsylvania route shared the common intended destination of Phoenixville, where fugitives hoped to reach the home of Elijah Pennypacker (1804-88), who helped them on to Philadelphia, Norristown, Quakertown, Reading, and other stations. This network of assistance gained the name “Underground Railroad” around 1804, and historian Larry Gara has estimated that as many as one thousand enslaved people a year joined the slow but steady traffic by the mid to late 1840s.

Tense Borders

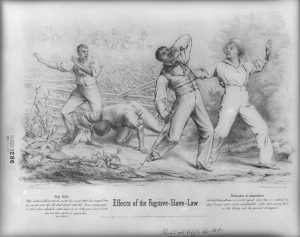

This activity led to tense interstate relations between border South states like Maryland and border North states like Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Well before the Civil War, conflicts that historian Stanley Harrold has labeled a “border war” over slavery took place in communities of southeastern Pennsylvania and southwestern New Jersey. Abolitionists put up armed resistance to slaveholders’ efforts to recapture slaves, in many cases rescuing the accused from courthouses and jailhouses. Two famous incidents, one at Swedesboro, New Jersey, in 1836 and one at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1847, led to considerable violence as fugitives and their allies fought hard to thwart the efforts of slave catchers. The rescuers in New Jersey succeeded in saving a Black family from a professional slave catcher from Philadelphia, but the group in Carlisle had mixed results and the situation ended in convictions for eleven rescuers. Perhaps the most famous of these rescue “riots” occurred in 1851 in Christiana, Pennsylvania, when a Maryland slaveholder was killed by Black men as they defended themselves against recapture. Despite the rising violence along the North/South border, escapes continued throughout the 1850s.

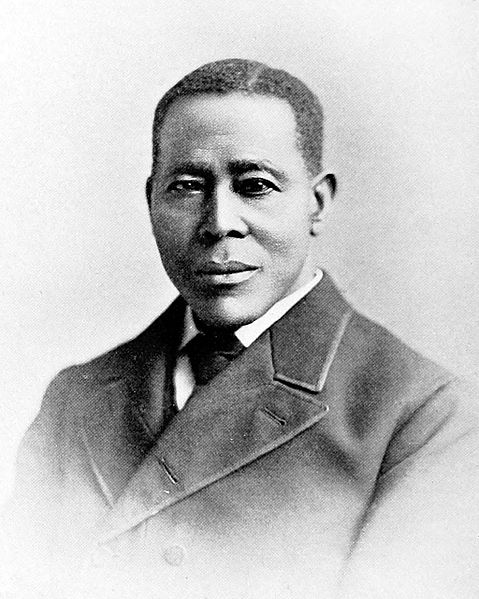

Historian Nilgun Okur has estimated that by the beginning of the Civil War nearly nine thousand fugitives made their way to Philadelphia, some passing through on the way to other destinations and others choosing to stay. In Philadelphia new arrivals found further assistance from the Vigilance Committee, led by prominent Black abolitionists like Robert Purvis (1810-98) in its early years and later by William Still (1821-1902). The group aided fugitives who reached Philadelphia by providing food, shelter, and clothing, sometimes in the form of disguises as they moved from one station to another.

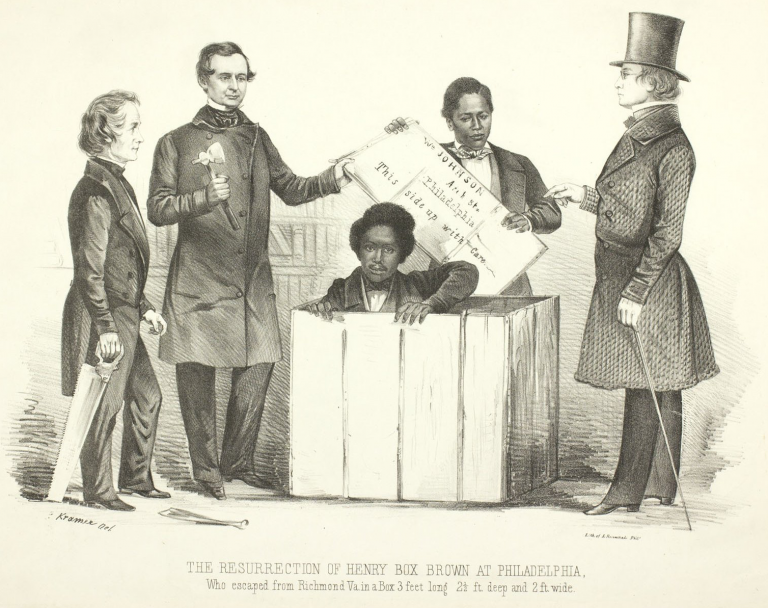

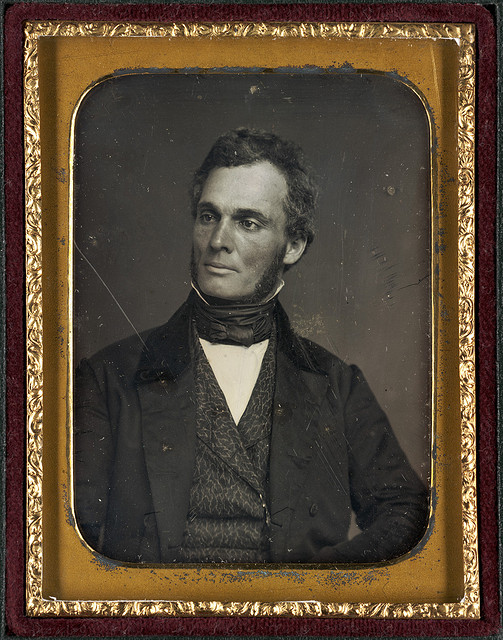

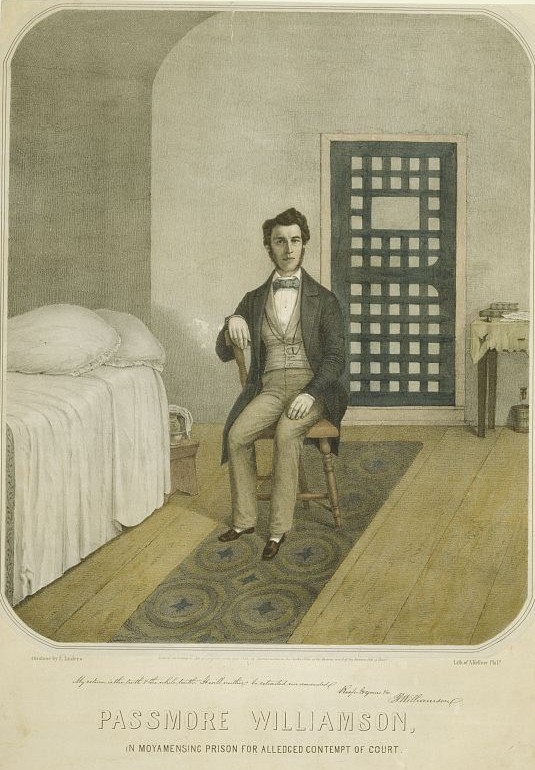

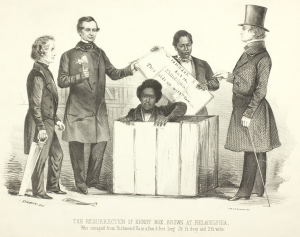

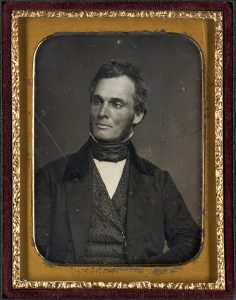

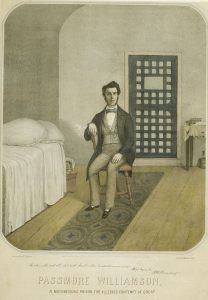

A New Jersey native, Still began working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1847, gradually advancing from custodian to clerk, then chair of the Vigilance Committee. His wife, Letitia (George) Still (1821-1906), played an important role by offering the Still home and by using her seamstress skills to sew the clothing and to raise money to help fund the operation. The Stills hosted a number of famous fugitives, including Jane Johnson (c.1814-72) and her sons, whom Still and fellow abolitionist Passmore Williamson (1822-95) dramatically rescued in 1855. In addition, Still received a number of now-famous fugitives in the Anti-Slavery Society office at 105 N. Fifth Street, including Henry “Box” Brown (c. 1816-97), who had himself shipped there from the South, and Still’s own brother Peter (1801-68).

Much of what historians know about these encounters comes from Still’s meticulous records and his resultant book, The Underground Railroad, published in 1872. According to his journal, preserved at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, he helped 485 fugitives in the city between 1852 and 1857. Still’s work and records clearly illustrate the importance of the free Black community to the operation and success of the Underground Railroad.

Philadelphia’s Aid Network

Still was building on a long tradition of free Black volunteers aiding fugitives. When he moved to Philadelphia he joined the largest and wealthiest northern free Black community, one with a host of churches, organizations, and mutual aid societies, including Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. These institutions helped foster a strong leadership class among Black Americans who had helped make Philadelphia an epicenter of American abolition even before the American Revolution. Though Philadelphia and the surrounding region were plagued by the same racism and animosity toward blacks that permeated American society, the region was also home to a supportive community of Quakers and other whites sympathizers. They founded organizations such as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society to fight against bondage and give aid to free Black people. This interracial cooperation was essential to the success of the Underground Railroad.

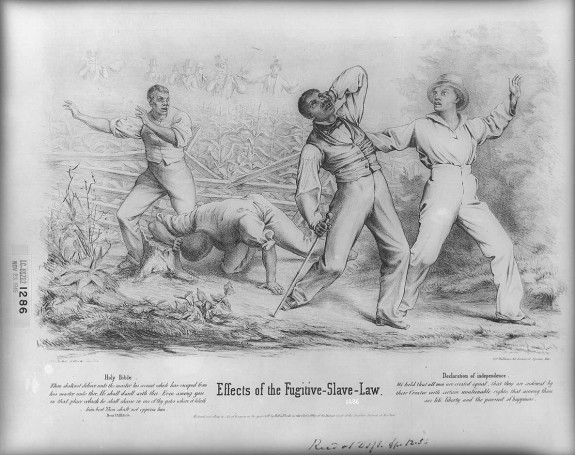

The conductors were violating Fugitive Slave Laws passed by the federal government in 1793 and 1850. The 1850 law in particular made it difficult to help fugitives because it required federal authorities to hunt runaway slaves and bystanders to participate in their capture when called upon. As a result, those who aided fugitives faced severe criminal penalties of six months in jail and fines of $1,000 as well as the possibility of civil suits from slave owners.

The story of the Underground Railroad provides an important example of interracial unity in the fight for social justice that began in the colonial era and continues today. White and Black abolitionists worked together to help enslaved Americans gain their freedom, pushing the nation to reach for the ideals in the Declaration of Independence. Everyday citizens who served as guides and conductors along the railroad had come to realize that the U.S.’s racial caste system harmed all Americans, and they employed nonviolent direct action to fight against the injustice. Their example animated later efforts such as the modern civil rights movement and remains relevant in the twenty-first century.

Beverly C. Tomek is the author of Pennsylvania Hall: A ‘Legal Lynching’ in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (Oxford University Press, 2013) and Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (NYU Press, 2011). She earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Houston and is associate professor of history and associate provost at the University of Houston-Victoria. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Christiana Riot Historical Marker

- Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church Historical Marker

- PhilaPlace: Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Narrative of Facts in the Case of Passmore Williamson (Library of Congress)

- PhilaPlace: Pennsylvania Abolition Society (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Pennsylvania Abolition Society Historical Marker

- Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society Historical Marker

- Robert Purvis Historical Marker

- William Still Historical Marker

- Henry Box Brown (Encyclopedia Virginia)