Union League of Philadelphia

By Allen C. Guelzo | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The Union League of Philadelphia, organized in 1862 as a political club for the support of the Union cause during the Civil War, developed into the premier urban social club of Philadelphia. Over time, it also became an important supporter of Republican political candidates and policies locally and nationally, acquired a significant collection of art and sculpture, and established various relief and civic programs for soldiers, veterans, and youth in the Philadelphia area.

At the time of Union League’s founding, Philadelphia was still a divided city with many economic, social, and cultural ties to the South. Indeed, before 1860 Philadelphia, with its proximity to the slaveholding South, had developed into what Pennsylvania political leader Alexander K. McClure (1828-1909) called “the great emporium of Southern commerce.” Although Philadelphia had been the home of the earliest American anti-slavery society, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, its record as a haven of abolitionist feeling was never significantly high. In the election of 1860, it gave Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln only a token majority of 2,039 votes out of over 76,000 cast. When civil war broke out in 1861, pro-Union Philadelphians were incensed that Philadelphians “who were almost in league with the Southern traitors were walking with heads high among our people.”

The League Takes Shape

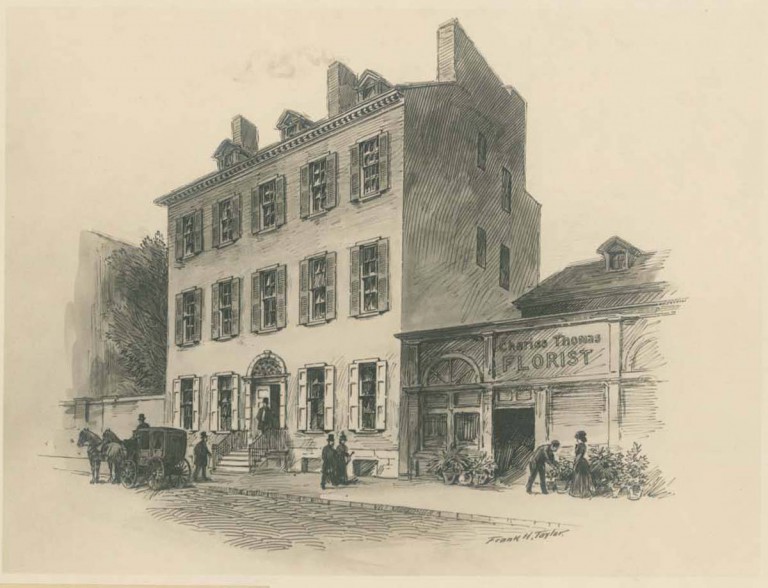

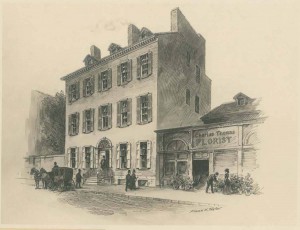

In November 1862, a small group of pro-Union Philadelphians met at the home of George H. Boker (1823-90), Philadelphia poet and playwright, at 1720 Walnut Street to form a “Union Club” that would act as a social successor to the Wistar Party (a voluntary association of prominent Philadelphia “gentlemen” who were members of the American Philosophical Society but had broken up over sectional issues) and an alternative to the politically-divided Philadelphia Club. But men like Boker thought a more politically active group was needed, and at the Union Club’s meeting of December 27, 1862 (at the home of Dr. John Forsyth Meigs [1818-82] at 1208 Walnut Street), adopted articles of association for an additional “Union League of Philadelphia.” Like the Union Club, the league’s only condition of membership was “unqualified loyalty to the government of the United States, and unwavering support of its efforts for the suppression of the Rebellion,” but its primary task was activist: “to discountenance and rebuke by moral and social influences all disloyalty to the Federal government … .” As a headquarters, the league initially rented space in the Hartman Kuhn mansion at 1118 Chestnut Street.

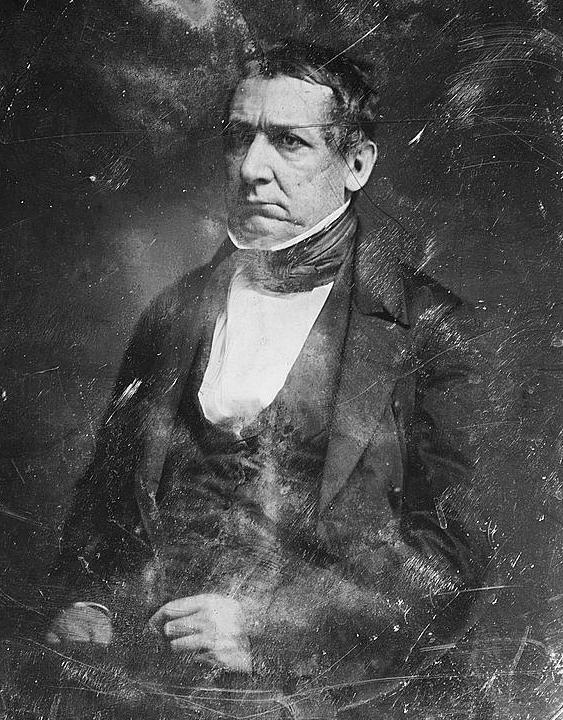

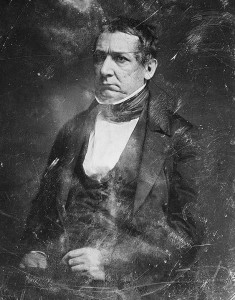

The league’s first general meeting for business convened on January 22, 1863, and elected former U.S. Treasury Secretary William Morris Meredith (1799-1873) as its first president and George H. Boker, the first secretary. Its first project was a series of pro-Union publications that could be distributed across the North by direct mail. Eventually, over the course of the war, the League’s Board of Publication issued over four and half million copies of 145 separate pamphlets, and employed a staff of twelve just to handle distribution. The league also raised money to provide bonuses for soldier recruitment, and in 1863 sponsored the organization of five Black regiments (3rd, 6th, 8th, 22nd and 25th U.S. Colored Troops) in Philadelphia and a “Free Military School” to train their officers. On June 16, 1863, the league played host to President Lincoln, visiting Philadelphia just after his nomination for a second term as president. By the end of the war, the league’s membership had grown to over a thousand, with almost half that number serving at some point in uniform.

The prestige it had successfully amassed during the war assured the league, and the Republican Party, a dominant place in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania politics, and helped usher in a Republican ascendency in Philadelphia that prevailed with little interruption for nine decades. As one indication of its self-confidence and status, the league built a new League House at Broad and Sansom Streets, turning away from the popular Greek revival style of Philadelphia’s pre-war architecture in favor of a lavish Second Empire building. The league, meanwhile, endorsed Radical Reconstruction, including Black civil rights, and made streetcar desegregation in Philadelphia one of its most successful post-war campaigns. In retaliation, an arsonist attacked the league’s new house on September 7, 1866, forcing the rebuilding of the upper floors and delaying its reopening until 1867.

In the post-Reconstruction decades, the league began a lengthy self-transformation into a cultural as well as a political institution. In 1882, the league established its own Art Association, which not only bought art works for the League House, but made the league the most important sponsor of city-wide art exhibitions until the opening of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the 1920s. In 1880, the league began purchasing properties along Moravian and Sansom Streets in preparation for constructing its first annex. In 1909 the cornerstone of the league’s final addition (extending to Fifteenth Street) was laid, with the Philadelphia architectural prodigy Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938) as its designer.

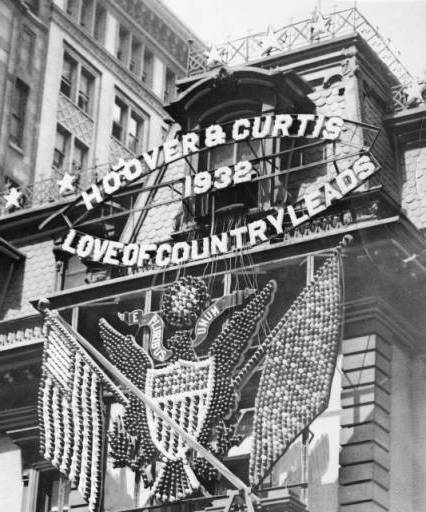

At the turn of the century, the league remained politically prominent in Republican politics at all levels. Of the seven governors of Pennsylvania between Reconstruction and 1906, five were league members. In Philadelphia, one of the league founders, Morton McMichael (1807-79), was elected mayor in 1866, and of the next eleven mayors up to 1916, eight were active Union Leaguers. But in the twentieth century, as the Republican ascendency built by the Civil War passed from the scene, the Union League lost its political influence, and increasingly turned inward as a refuge for the city’s business elites. After 1916, not a single Republican mayor of Philadelphia was a league member, and eventually, not a single member of the Republican City Committee; only one governor thereafter, William Sproul (1870-1928), belonged to the league.

The onset of the Great Depression jolted the league, and although the league was the first civil organization in the city to raise money for unemployment relief, the league itself suffered a 17 percent decline in active membership. It was also sharply critical of the New Deal policies of Democratic president Franklin D. Roosevelt; indeed, league president Otto Robert Heligman (1879-1941) called for the league’s rolls to be purged of any members who had voted for Roosevelt. When Roosevelt was reelected as president in 1936, a jubilant throng of Roosevelt supporters paraded down Broad Street to the league, where Democratic City Committee chairman John B. Kelly (1889-1960) climbed up the front portico of the League House and tore down the league flag.

The two world wars brought the league back into action as a visible patriotic organization. As Judge William W. Porter (1856-1928) reminded the league’s annual meeting after America’s entrance into the First World War in 1917, the founders of the league had never said a word about creating a “social” club. “Liberty Loans” managed by the league raised $17 million to support American involvement, and 200 of the league’s 2,600 members served in uniform. When the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 brought the United States into the Second World War, the league once again launched large fund-raising campaigns, and 187 league members joined the armed forces.

In 1959, facing the consequences of declining membership and significance, league president James M. Anderson (1900-77) appointed a committee to invent ways of keeping the league vital. Anderson chose for the committee chair J. Permar Richards (1915-2004), a former Olympic rower, and when Richards became league president in 1967, he aggressively expanded the league’s activities calendar to keep members’ attention from straying too much to the suburbs. In 1972, William Thaddeus Coleman Jr. (b. 1920), who later served as secretary of transportation under President Gerald Ford, became the league’s first Black member. In 1975, league president Burton Etherington (1909-2006) set aside the requirement (in place since 1893) that prospective members identify themselves as having never voted other than Republican for a state or national office. In 1982, President Perrin C. Hamilton (1921-2005) recommended admission of women members. At a stormy general meeting on January 11, 1983, to the dismay of Hamilton, 60 percent of the members present voted the measure down. The threat of legal action pushed the question back to the forefront of league attention, and at the behest of President Robert G. Wilder (1915-2002), the league membership reversed itself on May 19-20, 1986, paving the way for Mary G.H. Roebling (1905-1994) to become the league’s first woman member. The league’s first woman president, Joan Carter (b. 1943), was elected in 2011.

These changes set the stage in the 1990s for the most dramatic recruitment campaign the league had sustained. While many historic urban clubs of the Northeast, unable to offer activities that would attract clientele to a downtown location, closed their doors between 1990 and 2010, the league aggressively marketed itself as a downtown event and hotel location. It transformed its overnight accommodations into the Inn at the Union League, revamped its dining facilities, established a Heritage Center to house its archives and mount exhibits, and acquired its own parking garage. The league’s Youth Work Foundation, which began as an initiative of league president Millard D. Brown (1882-1957) in 1946 to promote “good citizenship” among Philadelphia’s youth, was by 2016 partnering with fifty-two Philadelphia organizations to recognize more than 250 high-schoolers at an annual “Good Citizen Day” at the league. In 2012, the Platinum Clubs of America ranked the league as the country’s number-one city club. The league’s prosperity is a marker of how a private institution can play a public role in the life of the city, and serve simultaneously a social and a civic goal without subtracting from either.

Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Republicans hurl a bitter accusation: You were a Democrat! (WHYY, April 5, 2012)

- Romney to raise money, but not campaign in Philadelphia Friday (WHYY, September 26, 2012)

- Pope to use Lincoln's Gettysburg lectern in Philadelphia (WHYY, August 7, 2015)

- Union League explores Philadelphia's history of conventional wisdom and blunders (WHYY, March 21, 2016)

- Union League's Good Citizen Award celebrates 70 yers of rewarding "good kids" (NewsWorks, May 12, 2016)