Vine Street Expressway

By Mary Yee

Essay

The Vine Street Expressway (Interstate 676), a 1.75-mile depressed limited-access highway traveling east-west across the northern edge of Philadelphia’s central business district, resulted from more than sixty years of effort to connect I-95 and I-76 and move traffic more easily between and through the city to surrounding counties in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Its route through Philadelphia has been important in the imagination of Philadelphia’s planners since the days of William Penn (1644-1718), whose surveyor Thomas Holme (1624-95) mapped Vine Street in 1682 as a 50-foot-wide right-of-way and northern city boundary extending from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Vine Street became lined with a mix of uses ranging from river-related activity at its eastern end, to theaters, saloons, and the Salvation Army near Franklin Square at Eighth Street, and stately townhouses farther west. In the 1830s the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, running lines west to Lancaster County, operated a rail depot at Broad and Vine. At the Delaware River, the Vine Street Landing was one of the busiest to serve river traffic and a ferry until the 1926 opening of the Delaware River Bridge (later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge). Commercial, warehousing, light industrial, and shipping-related businesses occupied two- and three-story buildings like those still evident in the early twenty-first century along the remains of Vine Street in Old City.

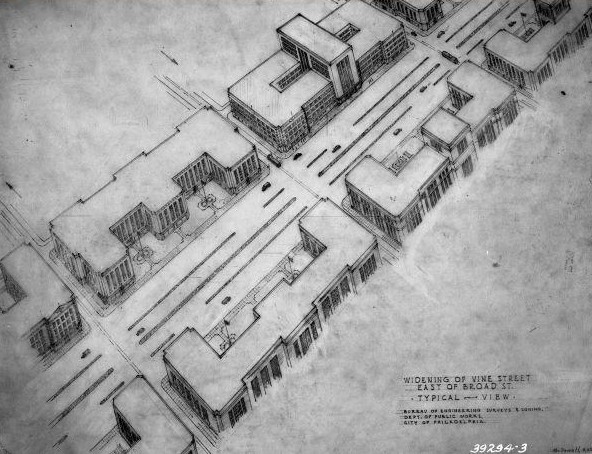

In the twentieth century, public projects and the widespread use of automobiles increased traffic along the Vine Street corridor and its importance as a collector and distributor of traffic. In 1918, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway from City Hall to the Philadelphia Museum of Art intersected Vine Street at Twenty-First Street, adding significant traffic. In 1926, the opening of the Delaware River Bridge channeled vehicles onto Vine at Sixth Street. By 1930, the volume forced city officials to consider large-scale traffic improvements. The early proposals for Vine Street included an elevated highway running one-way with Race Street also elevated and running in the other direction. From 1945 until 1973, plans evolved toward a four- or six-lane depressed highway running west from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River.

Vine Street Widened to Ten Lanes

After World War II, national and state priorities that favored interregional connections rather than links within cities delayed the expansion of Vine Street into an expressway. Nonetheless, local government officials and planners continually lobbied for upgrading Vine Street into a limited-access arterial highway. The 1947 “Better Philadelphia” exhibit, created by Edmund Bacon (1910-2005) and Oscar Stonorov (1905-70) as a vision for urban renewal, featured a highway system encircling the city with the Vine Street Expressway as a prominent segment. In anticipation of the expressway, the state widened Vine to ten lanes in 1951. Eight years later, a depressed limited-access section was completed from Twenty-First to Seventeenth Streets as part of construction of the Schuylkill Expressway.

The 1956 Interstate and Defense Highway Act, which designated the Vine Street Expressway as an interstate highway (and provided 90 percent federal funding, with the remaining 10 percent funded by the state), also made it feasible to extend the expressway from Seventeenth Street to I-95. This project was strongly supported by the Federal Highway Administration, PennDOT (and its predecessor agency), and city transportation officials, as well as the Center City business community. However, as the extension came closer to reality in the 1960s, it faced opposition from neighborhood groups. Plans presented in 1966 by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) stressed engineering priorities of providing the most efficient and cost-effective vehicular route. Local residents who attended the plan’s unveiling at a public meeting at the Free Library of Philadelphia objected, however, to the ways the highway might damage neighborhoods, citing socioeconomic, cultural, and historic preservation factors.

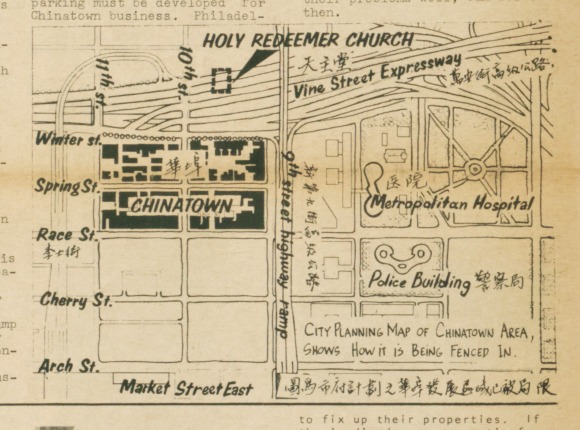

The Chinatown community adjacent to Vine Street between Ninth and Twelfth Streets faced the most potentially harmful effects. Following release of a draft Environmental Impact Statement in 1977 detailing the effects of the expressway, area residents represented by the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) protested vehemently that the expressway would negatively impact the physical, economic, and cultural character of the neighborhood, compounding the effects of other large-scale projects such as the Gallery at Market East (a mall), the Commuter Rail Tunnel, and “Independence Mall IV,” a project that took land by eminent domain in Chinatown along Ninth Street from Arch to Vine. Other unresolved issues included the proposed appropriation of a corner of historic Franklin Square, newly protected by the 1966 federal Historic Preservation Act, and the potential relocation of the Ben Franklin Bridge Monument, the present site of Isamu Noguchi’s 1984 sculpture at the base of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. The project also presented complex engineering challenges involving roadways and subway levels at Broad Street and Ridge Avenue and environmental quality problems such air and noise pollution in the vicinity of schools and residences. These all contributed to the opposition, which stalled the project until 1980.

Task Force Overcomes Prior Hurdles

In 1980, afraid of losing federal funding, Mayor William J. Green III (b. 1938) and the Secretary of PennDOT, Thomas D. Larson (1928-2006), created a multiagency task force whose objectives were to explore options for the expressway alignment and to develop those which best met transportation, community, and environmental needs. The task force embraced an innovative approach of seeking to balance cost-effectiveness, levels of transportation service, and environmental impacts—in particular, placing a priority on community preservation and cohesion. A public engagement process, which became an exemplar for transportation planners, included efforts to keep the communities along the corridor well informed, to provide ample opportunities for voicing concerns and recommendations, and to assign agency staff with skills in interacting with the public. The process produced revised plans for a scaled-down four-lane expressway, which by this time was all the more necessary because a companion Crosstown Expressway along South Street had been scrapped in the face of community opposition. In 1983, a final Environmental Impact Statement approved by the Federal Highway Administration allowed the Vine Street project to go forward.

When the completed Vine Street Expressway (I-676) opened in 1991, engineers anticipated that 30-minute peak-hour trips from river to river would be reduced to a few minutes. However, the expressway was adversely affected by conditions at both ends: at its western terminus by the narrow interchange with I-76 and to the east by peak-hour back-ups on I-95 or the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Extensive delays often resulted. Delays also accompanied necessary repairs and maintenance. In 2009 PennDOT replaced deteriorated concrete along the older segment of I-676, and in April 2015 a four-year project began to replace bridges over the expressway between Eighteenth and Twenty-Second Streets. The Vine Street Expressway continued to be a crucial and integral link in the highway system serving Philadelphia and the region.

Mary Yee is a doctoral student in literacy studies at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. Her research interests include community development, community health and literacy, and educational issues in immigrant communities. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.