Free Labor Pinafore

By Susan Drinan

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

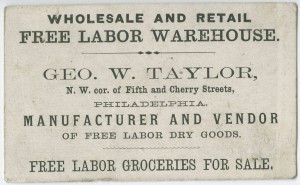

Pinafore, c. 1845, labeled “free cotton” to assure that the item was not produced by slave labor. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Friends Historical Association Collection, 1987, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

There are several ways of looking at the image of this little pinafore, a garment meant to be worn over a child’s dress. Made around 1845, it is an object related to the free-labor movement prior to the Civil War, an article of clothing that may have been made by someone for an abolition fair, and perhaps a connection to the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

The pinafore, hand-stitched with pleated edging around each armhole, has the original price tag of 12 cents still attached to the front. Turn the object to the back to find a clue to the pinafore’s significance for its maker and purchaser: an original paper tag that says “free labour cotton.” This meant that it had been made without the use of slave labor, part of an anti-slavery boycott movement that originated in England and spread to the United States in the 1820s. The movement came to Philadelphia in 1827 when Thomas M’Clintock (1792-1876) and others founded the Free Produce Society. In theory the idea of boycotting goods and selling only ‘free’ produce and goods was an excellent weapon against slave holders. In reality the cost of the non-slave goods, whether cotton or candy, was very high and many citizens did not feel the need to protest the use of slave-made goods.

This pinafore came to the Philadelphia History Museum in 1987 from the Friends Historical Association, which received it from local Quaker family. It is believed to have been made for or purchased at an abolition fair, a type of event organized by women to raise money to produce anti-slavery materials and to help free African Americans. A close look at the stitching and style of the pinafore suggests that it may have been made by someone not very knowledgeable about sewing. The stitches are uneven and one pleated sleeve edging was put in backwards. It is very small pinafore and may have been made as a sample. Most girls were taught to sew plain seams at the age of five or six and then gradually to learn to sew clothing. Stitching this small pinafore could have been within the scope of a child.

Among the organizations involved in local abolition fairs was the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS), Philadelphia’s first integrated abolitionist organization, founded in December 1833. The group’s primary fundraiser was an annual fair where handcrafted items such as needlework with abolitionist inscriptions, free labor goods, and anti-slavery materials were sold.

Lucretia Mott (1793-1880), a Philadelphia Quaker, was one of the founder of PFASS and a vocal critic of slavery. Other members included Charlotte Forten (1785-1884), wife of prominent African American James Forten (1766-1842), and her three daughters. After working for the cause of ending slavery in the United States the society disbanded in 1870 after passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Margaretta Forten (1806-75) proposed this resolution: “Whereas, the object for which this Association was organized is thus accomplished, therefore resolved, that the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, grateful for the part allotted to it in this great work, rejoicing in the victory which has concluded the long conflict between slavery and Freedom in America, does hereby disband.”

Developing the society as a functioning fund-raiser changed the way these women thought about their lives at a time when women were expected to lead quiet, domestic lives. They learned to speak out in public view, explain ideals to strangers, handle money, and work within a group to form plans and carry them through to fruition. These new ways of thinking and doing carried them on toward activism for women’s rights and suffrage.

Text by Susan Drinan, who retired in 2015 as registrar of the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Click on the waistband of the pinafore to learn more about abolition and slavery in Philadelphia.