Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens

By David Reader

Essay

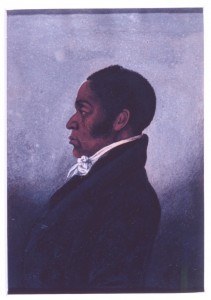

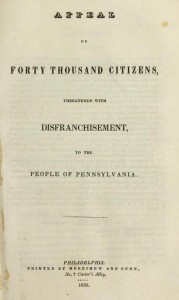

The Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Pennsylvania attempted to persuade Pennsylvanians to vote against the ratification of a new state constitution in 1838 because the word “white” had been inserted prior to “freemen” as a qualification for voting. Written by African American leader Robert Purvis (1810-98), the pamphlet highlighted the achievements, sacrifices, and value of the Black community to Philadelphia.

Under Pennsylvania’s first two constitutions, ratified in 1776 and 1790, Article III limited voting rights and elections to “freemen,” but definitions of “freeman” varied in individual counties depending on local politics and traditions. Some understood the term “freeman” to apply only to whites, while others did not. The commonwealth’s western counties, which had small populations of free Blacks, tended to allow them to vote. Eastern counties with larger populations of free Blacks–especially Philadelphia–discouraged them from voting though intimidation at the polls.

Philadelphia’s free Black community, the largest and wealthiest in the state, grew in the early decades of the nineteenth century as a destination for free Blacks from the South and runaway slaves. At the same time, tension over the issue of slavery increased, especially after Nat Turner’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1831 and the rise of racial abolitionism in the 1830s.

The explosive issue of race relations was one of many financial, governmental, and immigration problems facing Pennsylvania when the legislature called a convention to reform the state constitution in 1837. The convention began in May 1837 in Harrisburg but moved to Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia for its concluding sessions in November 1837 and February 1838. Initially, delegates made no recommendations to alter the language of Article III to prohibit free Blacks from voting. But Democrat John Sterigere (1793-1852) of Montgomery County seized on public opinion against Black voting rights and proposed to the convention that the language of Article III be changed to include the word “white” prior to “freemen” in order to exclude all Blacks, even if they paid taxes or owned property.

Thomas Earle (1796-1849), a Democrat from Philadelphia County, objected to changing the language and attempted to persuade the convention to seek a compromise to temporarily suspend Black voting rights throughout the commonwealth. He lost to a larger Democratic majority, which approved the change to Article III and proposed a new Constitution of 1838 for ratification. Similar actions occurred in other states during this period as politicians attempted to prevent Blacks from gaining the same voting rights as white men, whose access to the polls was increasing with changes in voting qualifications such as reduced taxes or land-owning requirements.

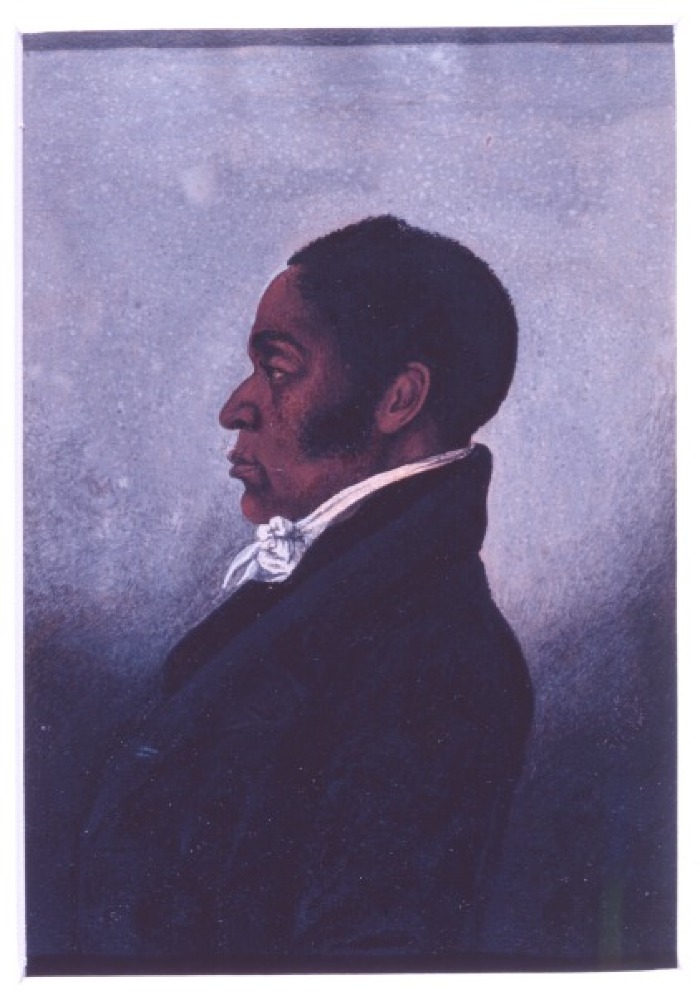

Philadelphia’s Black community responded to Pennsylvania’s proposed constitution with the Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, to the People of Pennsylvania. In the tradition of African American leaders such as Absalom Jones (1746-1818), Richard Allen (1760-1831), and James Forten Sr. (1766-1842), Robert Purvis emphasized the worthiness of Philadelphia’s Black community. Purvis systematically presented an argument based on history, statistical data, economics, and politics to combat public misconceptions about African Americans.

The Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens invoked the founding documents of Pennsylvania and the nation to argue that it would be consistent with previous generations to ensure suffrage to freemen without the mention of a specific race. The pamphlet pointed out that during the colonial period, white indentured servants as well as Black slaves were not permitted to vote because they lacked the status of freemen. “White” was not included as a qualification for voting in either the 1776 or 1790 Pennsylvania constitutions.

To support the claims of the Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery compiled a census as evidence that Philadelphia’s Black community provided the city with revenue, laborers, and taxpayers who contributed to its economic success. The census demonstrated that compared with whites, African Americans made up a substantially lower proportion of the poor and people receiving aid. In fact, the Black community paid more to provide relief for the poor than it received in return. Purvis used the statistics to rebuke a public image of idleness. Recognizing the connection between actions in Pennsylvania and increasing racial tensions in the nation, Purvis charged the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention with having, “laid our [Black] rights a sacrifice on the altar of slavery.”

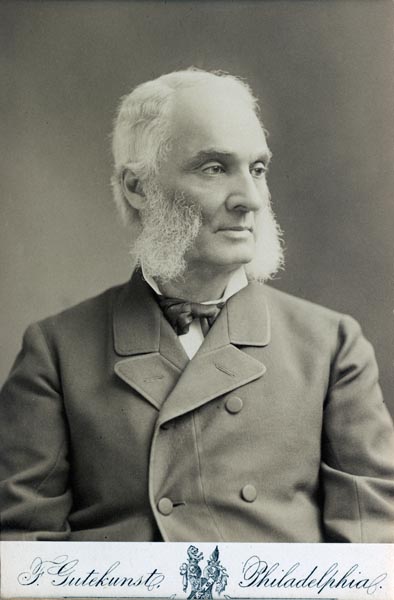

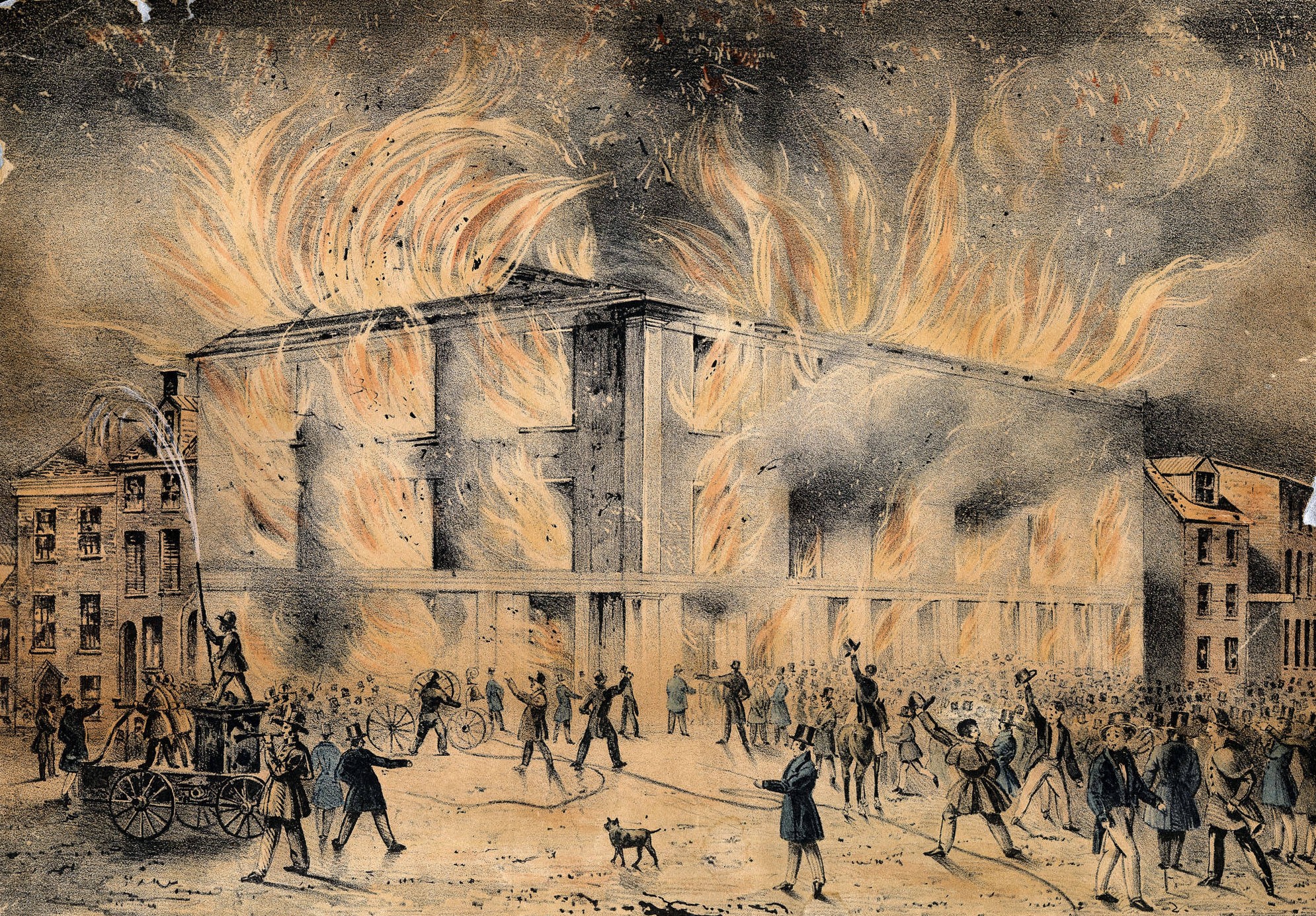

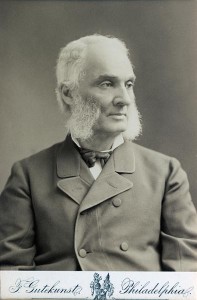

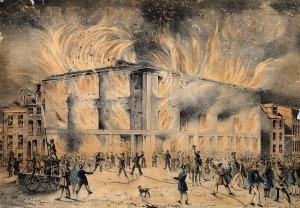

Voters ratified the Constitution of 1838 by a margin of a little more than one thousand votes—113,971 to 112,759—on October 9, 1838. African Americans continued to petition the legislature to reinstate suffrage for free Blacks, but their petitions were left unanswered. Racial tensions turned to violent riots targeting African Americans and attacks on a newly erected abolitionist meeting place, Pennsylvania Hall. Although a new generation of leaders including Jacob C. White Jr. (1837-1902) continued the fight for suffrage, African Americans in Pennsylvania did not regain the vote until the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1870) extended voting rights to Black men throughout the nation.

David Reader teaches history at Haddonfield Memorial High School and was the recipient of the James Madison Memorial Fellowship in 2007. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Black Founders: The Free Black Community in the Early Republic (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Jacob C. White, Jr. Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- James Forten Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Musical Fund Hall (PhilaPlace)

- Pennsylvania Hall Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Robert Purvis Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)