Atlantic World

Essay

Philadelphia’s nearest ocean has left a profound imprint on the region’s politics, economy, and culture, but the relationship between the Delaware Valley and the Atlantic basin has passed through several distinct phases. From its beginnings as a European settler colonial city, Philadelphia matured into an important Atlantic node, serving as a commercial hub, an immigrant entrepôt, and a center of revolutionary conflict over liberty and enslavement. Over the course of the nineteenth century the region became an industrial dynamo whose workshops and factories persuaded emigrants to brave the Atlantic crossing and helped the United States challenge European power. As Greater Philadelphia’s relationship to other parts of the globe grew in the later twentieth century with new patterns of trade and immigration, the relative importance of the Atlantic to regional fortunes diminished, but collective memory of ties to Europe and Africa remained central to civic identity. Atlantic World trends and connections have shaped the city and the region, just as ideas, people, and goods from Philadelphia shaped the Atlantic World.

Philadelphia’s connections with the Atlantic predated William Penn’s founding of the city in 1682. Imperial rivalries among European powers in the seventeenth century made the Delaware Valley a site of colonization, conflict, and diplomatic wrangling. In 1638, the powerful Swedish monarchy established the colony of New Sweden in the area that later became portions of Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. The colony survived until 1655, at which point the Dutch Republic conquered it and incorporated New Sweden into New Netherland. Less than ten years later, in 1664, the English took over New Netherland (renaming New Amsterdam as New York in the process), although the Dutch recaptured the colony during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-74). The Treaty of Westminster (1674) relinquished New Netherland to the English. Such contests among European monarchies and republics gave the Delaware Valley a cosmopolitan hue. Before Penn arrived, Lenape people lived alongside Swedes, Dutch, Finns, and Germans; enslaved African people have been documented around the Delaware region from 1639.

Within a few decades of the city’s founding, Philadelphia had become a bustling port city and a center of transoceanic trade. Commercial networks bound Philadelphia to the Atlantic World. By the 1750s, Philadelphia had outgrown Boston to become the busiest port in British America. Its shipping carried flaxseed exports to Ireland and sugar grown by enslaved people in the Caribbean for refining along the Delaware waterfront. Philadelphia, in other words, quickly became integrated into the dense web of connections stretching across the Atlantic and beyond. From the beginning, pirates took advantage of these connections as they preyed on vessels. William Penn discovered to his dismay in a 1699 visit to his city that pirates thrived in Philadelphia, where they received significant support from some of the city’s well-to-do residents and royal officials, and from whence they ventured to target Muslim pilgrims in the Indian Ocean.

Religious Freedom, Economic Opportunity

Transatlantic migration peopled early Philadelphia and its surroundings. Irish, English, Welsh, and German Quakers accompanied Penn across the ocean, drawn—like other dissenting groups—by Penn’s promise of the religious freedom denied to them in the Old World. Other newcomers in the eighteenth century, frequently from the British Isles and Germany, flocked to the rich agricultural land to the west of the city. Their small farms offered better economic opportunities than could be found in Europe, giving the region a reputation as “the best poor man’s country.”

But that land belonged to other people and, consequently, European immigration to the Delaware Valley assumed a settler colonial character marked by diplomacy and conflict. Negotiations between Lenape people and Europeans in Greater Philadelphia became an important, if much mythologized, part of the early history of the region. Some Native Americans appear to have preferred dealing with pacific Quakers and established productive relationships with them. At least in the beginning, Penn and Quakers seemed to negotiate in good faith. However, as time passed, more and more Europeans arrived in the region, eyed Native American lands covetously, and plotted to appropriate further territory for themselves. By the mid-eighteenth century, Scots Irish settler colonials to the west of Philadelphia blamed the colony’s Quakers for checking further conquest. In 1763, a marauding band known as the Paxton Boys massacred the residents of a Susquehannock settlement in Lancaster County that had been on good terms with the colony. Such instances reveal how voluntary European migration across the Atlantic led to the violent expropriation of the region’s Native peoples.

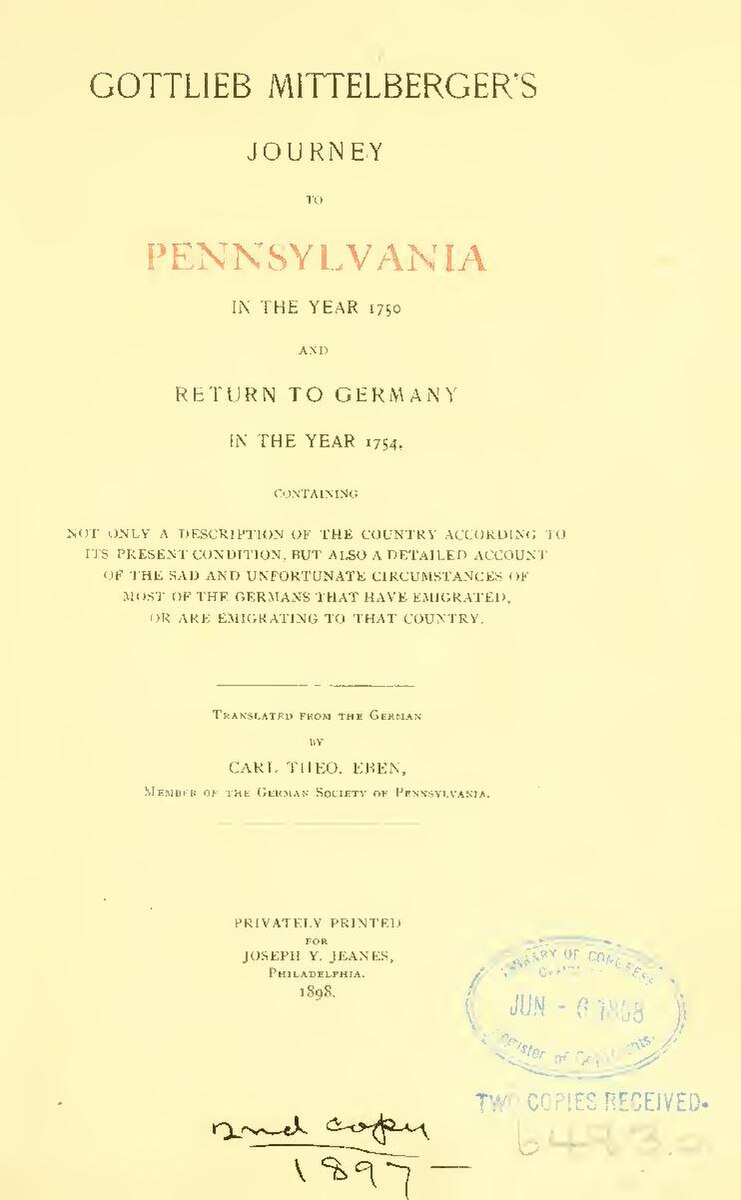

Not all passages across the ocean, though, were voluntary. Indentured servitude and African enslavement—the first a temporary form of unfree labor, the second a permanent one—also crossed the Atlantic. Some European immigrants could pay their fare, but those who could not traded up to seven years of their future labor for passage to the Americas. Conditions indentured servants experienced varied wildly across different times and places, but most did not have easy lives. The German schoolmaster Gottlieb Mittelberger sought to discourage such emigration from his homeland. His Journey to Pennsylvania (1756), based on his voyage from Rotterdam to Philadelphia and his subsequent sojourn in Lancaster County, did not pull any punches about the misery and exploitation that indentured servants and other immigrants often faced.

Trafficked African people, assigned by their captors with the inheritable status of enslavement, also arrived in Philadelphia, sometimes on ships outfitted in the city. In the early years of the colony most came from the Caribbean. However, when that supply became more fraught, as it did during Seven Years’ War, Philadelphian traffickers turned to direct importation from Africa. At the beginning of the American Revolution, Philadelphia contained roughly seven hundred enslaved people, who brought with them elements of African and Caribbean culture like pepper pot soup. Philadelphia and its hinterland—where enslavers held over two thousand more people as property—never developed the export-oriented plantation economy that flourished in Virginia, the Carolinas, and the Caribbean. That said, enslaved people served in households, craft industries, and aboard ships. Furthermore, Philadelphians who did not enslave people themselves often purchased the products of enslaved labor, invested in slaving voyages, and facilitated the buying and selling of their fellow human beings.

Clashes Abroad Reverberate in Philadelphia

A region scarred by Black enslavement became a cradle of white liberty over the middle decades of the eighteenth century. As the foremost port in British North America, Philadelphia played a critical role during the Seven Years’ War, the Imperial Crisis, and the American Revolution. Each of these upheavals had Atlantic origins and ramifications. The struggle between Great Britain and France in Europe reverberated in the Americas. Similarly, events that occurred in the Americas, like George Washington’s military encounter with Joseph Coulon de Jumonville in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, rippled across the Atlantic as well. For Philadelphians, the backdrop of conflict among great powers intensified existing transatlantic connections and created opportunities for new ones. Benjamin Franklin spent considerable time in Great Britain in the 1760s and 1770s trying to prevent war between Great Britain and the thirteen colonies, as well as securing jobs for his friends and associates. Franklin had long been an Atlantic celebrity and his growing disillusionment with Great Britain represented the fraying political and intellectual links between Parliament and its American possessions.

Over these years Philadelphia and its surrounding region became a key battleground in the age of Atlantic Revolutions. Between 1770 and 1833, violent upheavals transformed France, Haiti, and vast colonized regions of North and South America into republics. In 1776 the Second Continental Congress, composed of delegates who were often born and educated in Europe, met in Philadelphia to sign the foundational document of the new United States. The Declaration of Independence reverberated across the ocean and reflected the influence of transatlantic thought. Its authors presented facts to the candid world and addressed a much broader audience than the residents of the thirteen colonies. The draft of Thomas Jefferson also revealed the western drift of Enlightenment ideas. He adapted, for instance, the claim of the seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke that men had the right to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Property.” But the declaration, and the new republic it announced, were also shaped by Atlantic World slavery. As scholars have demonstrated, ideas about white freedom and liberty developed in tandem with racialized ideas about Black enslavement and submissiveness. Jefferson’s initial draft of the declaration placed the onus for slavery solely on Great Britain. From London, it prompted the lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson to wonder why the loudest cries for liberty emanated from the mouths of enslavers.

The Imperial Crisis and the American Revolution severed links to Britain. For some in the Delaware Valley the divorce proved hard to imagine. By no means did all residents in the region flock to the Patriot cause, and “Loyalists” who wanted to maintain relations with the mother country could be found among both the economic elite and ordinary people. The Delaware Valley’s Atlantic merchants confronted a difficult dilemma. Ties to the British Empire granted local merchants access to imperial markets, not least in the Caribbean, where food grown in Philadelphia’s fertile hinterland had been exchanged for sugar and cash crops. War cut off such long-established trading routes and led to the questioning of loyalties. Quaker merchants like Henry Drinker often had deep ties to Great Britain. Drinker and his wife Elizabeth faced the challenge of trying to thread the needle between making concessions to revolutionaries while maintaining their Atlantic connections. Revolutionaries eventually arrested him for treason, imprisoning him in Virginia, while Elizabeth navigated life in British-occupied Philadelphia during 1777-78. After regaining control of the city, Patriots held 638 “Tory” collaborators as suspected traitors. The Drinkers, embedded in Atlantic World networks, suffered as they attempted to navigate the complex politics of the Revolutionary era. Other Philadelphian merchants turned their gaze to the west, looking for new markets in China and the Pacific.

Ripples of the American Revolution

The Revolutionary War, like the Seven Years’ War before it, recalibrated Atlantic relations in other ways, too. At Valley Forge in 1777-78 the Prussian officer Baron von Steuben helped to drill George Washington’s army. The British evacuated Philadelphia in June 1778 and retreated to New York. Around three thousand Philadelphian loyalists left the city with the British military forces, joining a wider exodus of Tories and their allies (including enslaved Black Americans who had been promised freedom in exchange for military service) to Canada and Britain. Von Steuben’s work at Valley Forge helped Washington fight the British to a draw at Monmouth. A few months before Patriots retook Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin, having been dispatched the Paris, steered the rebel colonies into a crucial alliance with France that helped to determine the outcome of the war. The decision to use Franklin as a diplomat proved a sound one. He fascinated the French, who saw him as the premier example of American genius, and he played his role with aplomb.

In the decades following the American Revolution, Philadelphia remained closely connected to the political currents of the Atlantic World. The ideas of the American Revolution were carried east and south. Revolutions erupted elsewhere—in France, in other parts of Europe, in Haiti, and in Spanish America. The career of Thomas Paine indicates their entangled paths. Paine, who was born in Norfolk, England, had been convinced by Franklin to go to the Americas. Arriving in Philadelphia in late 1774, his influential pamphlet Common Sense made the case for revolution in plain language that appealed to a wide readership. In the doldrums of 1776, Paine’s The American Crisis helped buoy Patriot morale. After the American Revolution ended, Paine traveled to France and served as a member of the National Convention, where he narrowly avoided the guillotine after falling out of favor with leading Jacobins. Paine’s career as an Atlantic revolutionary, with Philadelphia at its center, demonstrates how ideas easily crossed oceans.

As a major port city and an Atlantic World hub, Philadelphia often welcomed revolutionaries like Paine, while selectively supporting revolutions elsewhere. French Minister Edmond-Charles Genêt, also called Citizen Genêt, arrived in Philadelphia to a rapturous welcome in 1793. Genêt angered George Washington by attempting to subvert Washington’s proclamation of U.S. neutrality in the brewing conflict between Great Britain and France. Another figure to become embroiled in partisan battles of the early republic was the Polish nobleman Tadeusz Kościuszko. Having fought with the colonials during the American Revolution and then for Poland against Russia and Prussia, in 1797 he returned as a political exile to the United States, where he lived briefly in Philadelphia until leaving for Europe in 1798. Kościuszko wrote a will that named Thomas Jefferson as the executor, dedicating his estate to purchasing the freedom of enslaved people and providing them with education.

Exiles Find a Home

Whether as a place of refuge from revolution and reaction or as a source of support for insurgents, the Delaware Valley became enmeshed with tumultuous upheavals across the Atlantic. When revolution erupted in Haiti in 1791, French masters fled the island, forcing many of the people they enslaved to join them. The exiles who arrived in Philadelphia brought firsthand accounts of the hemisphere’s first Black-led revolution, which energized both abolitionist and anti-abolitionist politics. Another Francophone uprooted by revolutionary wars was Joseph Bonaparte, who fled to the United States after his brother Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Following a short sojourn in Philadelphia he moved out to an estate in nearby Bordentown, New Jersey, where he spent most of his remaining years. Supporters of the Greeks in the Greek War for Independence from the Ottoman Empire raised money for the cause and even tried to persuade the United States to intervene. And in 1848, citizens gathered on Independence Square to welcome the proclamation of a new French Republic. People did not always like the direction foreign revolutions took, but Philadelphians, both Black and white, recognized their city’s place in a revolutionary Atlantic World.

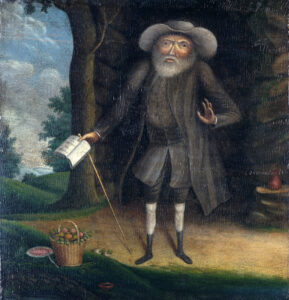

Black Philadelphians insisted that those Atlantic revolutions had to reckon with enslavement—the cry of liberty rang hollow if new republics were built on the back of forced labor. Finding allies, however, did not prove easy; abolitionism was never more than a minority sentiment among white people in the eighteenth century. That said, some of the region’s Quakers, African Americans, and other friends of liberty raised their voices in favor of ending enslavement and emancipating enslaved people. Connections to the Caribbean and Europe shaped antislavery activism in the Delaware Valley. An extraordinary individual named Benjamin Lay, a Quaker immigrant, became one of the region’s earliest abolitionists. Born in England the same year as Philadelphia’s founding, Lay spent years traversing the Atlantic as a sailor, left for Barbados, and from there migrated to Philadelphia. Lay’s abolitionism sprang from his ardent Quaker faith, as well as his experiences in Barbados, where he witnessed enslavement’s brutality firsthand. While in Barbados, Lay and his wife Sarah held meetings at their house and served meals to enslaved people, which infuriated white slaveholders. After he and Sarah relocated to Philadelphia, Lay tried to convince fellow Quakers in the region to emancipate enslaved people. While some Friends had rejected enslavement before Lay’s arrival, his activism led to his disownment, and he retreated to a cave he converted into a cottage in Abington, Pennsylvania. From there Lay continued to urge the region’s Friends to acknowledge Atlantic enslavement as apostasy. By the end of his life more Quaker voices in the region had begun to proclaim the abolitionism gospel, including the New Jersey merchant John Woolman, a member of the Chesterfield Friends Meeting, who died in Britain on an antislavery mission, and the French-born religious refugee Anthony Benezet, who played an important role in founding the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage in 1775. The first abolition society in the Americas, it was later reorganized as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage (usually referred to as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society) in 1789.

The AME Church Goes Global

In the decades that followed, Black abolitionists in Philadelphia built institutions and cultivated connections that reached across the Atlantic. By doing so they recognized that the struggle against enslavement in the United States was part of a wider battle for rights that extended to Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa. Richard Allen, building on his efforts in establishing Philadelphia’s Free African Society in 1787 and Mother Bethel Church in 1794, founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1816 and became the church’s first bishop. AME churches subsequently sprang up all over the globe. By the end of the nineteenth century they had reached Bermuda, West Africa, and South Africa. An African American institution that began in Philadelphia therefore shaped the global spread of Black Christianity. Bishop Allen supported abolition, as did James Forten, a self-made sailmaker who after an initial flirtation with the idea of “colonizing” formerly enslaved Americans in Africa or Haiti became a fierce opponent of such schemes and an ardent advocate of an immediate end to enslavement. But the Atlantic connections of Philadelphia’s Black abolitionists are perhaps most evident in the career of Robert Purvis. Born free in Charleston, South Carolina, to parents of British, Moroccan, and Jewish roots, Purvis migrated to Philadelphia, where he helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society. Like many of his fellow abolitionists, Purvis sought to rally support in the United Kingdom, which had put enslavement on the path to extinction in its own colonies, and he traveled back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean on fundraising missions while corresponding with prominent British figures in the antislavery movement. When, on August 1, 1842, Black abolitionists marched through the southern wards of the city to mark the eighth anniversary of abolition across the British empire, a rampaging white mob threatened to burn down Purvis’s house.

The Lombard Street Riot of 1842, as it became known, proved just one of a series of riots that pitted rival immigrant and racial groups against one another in the “turbulent era” of the 1830s and 1840s. Tensions over religion, enslavement, and politics that reached across the Atlantic Ocean played out on the streets of Philadelphia. Immigration from Europe continued in the decades after the Revolution, with British, Germans, and Irish (especially after the beginning of the Potato Famine in the 1840s) the most heavily represented. Old World experiences shaped their politics. British Chartists, veterans of the struggle for the vote in the United Kingdom, welcomed the political rights denied to them in their country of origin. Irish Catholics gravitated toward the Democratic Party, in part due to the hostility of prominent Democrats like Andrew Jackson toward Britain. Indeed, the frequency with which Irish Catholics participated in anti-abolitionist violence owed something to their equation of abolitionism with support for the British crown. Germans, on the other hand, often backed the new antislavery Republican Party in the 1850s, and many of them saw the fight against enslavement as a continuation of the revolutions of 1848 in Europe. Catholic immigration in particular met a nativist backlash. The Philadelphia Nativist Riots of 1844, which saw the county placed under martial law, sprang from rumors that Irish newcomers wanted to replace the Protestant King James Bible in the city’s public schools. Philadelphia became a battleground in a conflict that stretched back to the English colonization of Ireland and break with Rome.

Movement across the ocean brought epidemics as well as people. Diseases rarely remained within the borders of one country; they spread rapidly across an increasingly connected world. Philadelphia’s status as an Atlantic port increased its vulnerability. A yellow fever epidemic in 1793, possibly carried on ships transporting French enslavers fleeing the Haitian Revolution, killed at least five thousand Philadelphians and sent tens of thousands fleeing from the city. Yellow fever recurred on a less destructive scale for decades. After the epidemic in 1793, the city decided to build new waterworks and engaged British-born architect Benjamin Latrobe to design them. Latrobe built the waterworks in a neoclassical style that evoked Athens. Cholera too crossed the Atlantic and caused epidemics in 1832, 1849, and 1866. By the late nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s sanitarians were learning from the hygiene measures that had begun to control such diseases in Europe.

The Arts and Sciences Flourish

Such exchange of knowledge had long been a feature of the region. The arts and sciences flourished in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin and John Bartram’s establishment of the American Philosophical Society in 1743 marked the first of many efforts for Philadelphians to demonstrate leadership in the arts and sciences. Philadelphia was the first city to lay claim to the mantle of the “Athens of America,” although some people later argued that Boston also deserved the title. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia was founded in 1812, in part to impel the creation and diffusion of knowledge about the sciences and in part to place science in the United States on a par with its status in Europe. While Atlantic World rivalries proved important, the flourishing of the arts and sciences in Philadelphia also sprang from cultural exchange and connection, with leaders in fields as diverse as medicine (Benjamin Rush), botany (John Bartram), and history (Henry Charles Lea) all maintaining close links through either education or correspondence to their European counterparts. The French, in particular, had a powerful influence on the city, not least through the career of the merchant Stephen Girard, an immigrant who became one of the richest men in the United States and left most of his estate to his adopted city. Such figures cultivated and affirmed Atlantic World relationships.

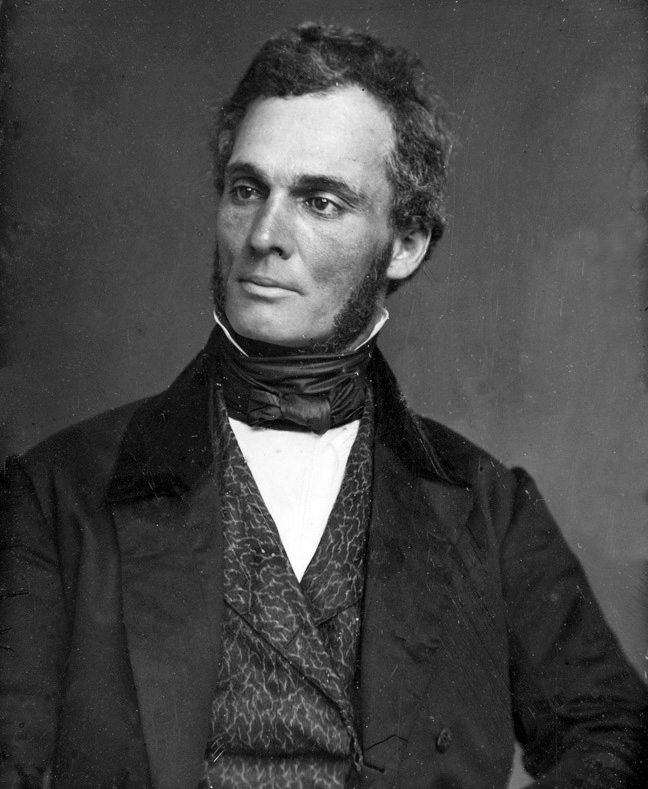

If Philadelphia’s intellectual connections to the Atlantic remained a constant across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the region’s significance to the transoceanic economy eventually started to wane in the 1800s. In contrast to Washington, D.C., which foreign observers and even many people in the U.S. derided as a miasmic swamp or a sleepy, provincial village, Philadelphia remained an Atlantic financial hub well into the 1830s. The Second Bank of the United States, based on Chestnut Street and boasting a federal charter from its foundation in 1816 to 1836, maintained transatlantic financial ties between the U.S. and Europe, particularly Great Britain. Its demise at the hands of President Jackson strained those relations, which suffered further when Pennsylvania defaulted on its debt payments to European creditors in 1842, prompting the English Lake poet (and out of pocket “surly creditor”) William Wordsworth to rail against the commonwealth’s “degenerate Men.” Furthermore, Philadelphia lost ground to New York City as an Atlantic port, as the Erie Canal (among other factors) fueled Manhattan’s ascent as the financial capital of the United States. The source of Greater Philadelphia’s wealth shifted from commerce to manufacturing, as the Athens of America transformed into the workshop of the world, which increased local support for high protective tariffs to protect home industry. These higher tariffs, however, made it harder for the city to cultivate European markets. Some Philadelphians nevertheless found overseas clients. Joseph Harrison Jr., for example, built locomotives for Russia and Czar Nicholas I awarded him a gold medal for completing the St. Petersburg-Moscow Railway. After his return to Philadelphia, Harrison amassed an impressive art collection, which he displayed at his mansion off Rittenhouse Square. Harrison, like some of his contemporaries, remained connected to the Atlantic World and prioritized connections and cultural exchange.

Philadelphia’s reputation as an Atlantic center of politics, finance, and commerce may have declined over the course of the nineteenth century but its links to its nearest ocean persisted in other respects. Immigration, which had slowed during the Civil War, accelerated again in the decades that followed. These arrivals increasingly came from eastern and southern Europe— especially Italy—rather than the western and northern reaches of the continent. Their children and grandchildren then often made the Atlantic crossing in reverse to fight in that continent’s wars. U.S. intervention in European conflict left a marked impact on the region’s economy and society. World War I and World War II stimulated ship production along the Delaware. During the latter, the Philadelphia Navy Yard employed over fifty thousand workers, whose labor made Philadelphia a vital part of the “Arsenal of Democracy.” Europe and Africa continued to exert an influence in art, design, and politics, too. Jacques-Henri-Auguste Gréber, a French landscape architect, designed and built the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and a proponent of Pan-Africanism, had a following in Philadelphia. Garvey is not the only example of Philadelphia’s connections to Africa. After the loosening of federal restrictions on immigration in the 1960s, Ethiopians, Ghanaians, Liberians, and Nigerians were prominently represented in the new African diaspora of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries to Philadelphia.

Bonds of Culture Persist

Philadelphia’s Atlantic connections remained evident in spaces and civic life of the twenty-first century region. The Irish Memorial near Penn’s Landing, dedicated in 2003, sought to remind visitors about the migrants who built the city. The Mummers Parade could trace its roots back to older immigrant traditions from England, Germany, and Sweden. Annual Columbus Day celebrations testified to both the strength of Italian-American pride and the contested legacy of European colonization. Founders of the ODUNDE Festival, held the second Sunday in June, sought to celebrate the history and heritage of African peoples around the globe and created one of the longest-running and largest African American street festivals in the United States. Philadelphia’s historical connections to the Atlantic—forged in cultural exchange, revolutionary conflict, and the movement of peoples and revolutionary ideas—helped make the twenty-first century city a mecca for tourists. Yet such connections have sometimes underpinned a resurgent nativist politics that echoed an earlier era, as some residents used the region’s European cultural heritage to question the place of new immigrants from the Americas and Asia in the city. Philadelphia connections by the twenty-first century were global rather than primarily Atlantic. But the ocean the Delaware River empties into made the city a political and economic hub and the links it enabled remained lodged in civic memory.

Evan C. Rothera is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Arkansas–Fort Smith. He is author of Civil Wars and Reconstructions in the Americas: The United States, Mexico, and Argentina, 1860–1880 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2022) and coeditor, with Brian Matthew Jordan, of The War Went On: Reconsidering the Lives of Civil War Veterans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020). (Author information current at time of publication).

Copyright 2026, Rutgers University.