Automats

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

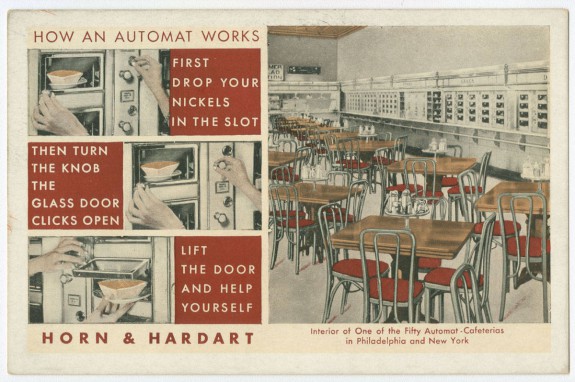

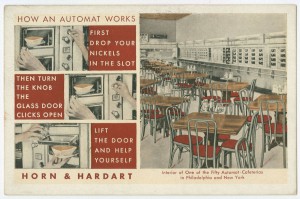

Beloved by generations of diners and immortalized in art, song, cinema, and poetic verse, Automats, also known as “automatics” or “waiterless restaurants,” were popular manifestations of an early-twentieth century modernizing impulse. Influenced by studies of scientific management by Frederick W. Taylor and the widespread use of the assembly line, the Automat removed the process of ordering food through a professional waitstaff and allowed customers a faster dining experience via coin-operated vending machines. Designed to streamline dining out while offering a broad choice of freshly prepared menu items, Automats were integral features of Greater Philadelphia’s restaurant industry from the early 1900s through the mid-1960s.

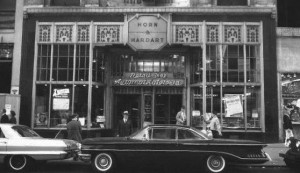

Automats first appeared in Germany and Scandinavia in the 1890s. The first Automat in the United States is credited to Joseph Horn (1861-1941) and Frank Hardart (1850-1918), whose Philadelphia baking company imported the technology from Quisiana, a Berlin-based manufacturer. While European Automats were small, novelty-like affairs with unreliable brass machines, the American version pioneered by Horn and Hardart was larger and grander, with Art Deco accents, chrome paneling, stained glass windows, vaulted ceilings, and improved mechanization.

Philadelphian Horn and New Orleans transplant Hardart had operated luncheonettes and bakeries in Center City since partnering in 1888. For their first Automat, they chose a site at 818 Chestnut Street. It proved an immediate sensation. After it debuted June 9, 1902, the Philadelphia Inquirer noted that Horn and Hardart had solved the city’s “rapid transit luncheon problem” of feeding people on the go. Their official slogan, “less work for mother,” affirmed their goal for faster restaurant service.

Customers from politicians and factory workers to secretaries and policemen enjoyed a plethora of food choices and comparatively low cost. For less than fifty cents, diners could eat three meals a day. With breakfast, lunch, and dinner items in climate-controlled glass cases that could be quickly accessed, the Automat not only appealed to the urban masses but with its speed and consistency, marked the rise of the fast food industry in the United States. Horn and Hardart opened their second Automat in 1905 at 101 S. Juniper Street, third in 1907 at 909 Market Street, and a fourth in 1912 at 21 S. Eleventh Street. Initially, cooks and prep kitchens were housed on site in the rear or basement. To maintain quality as the company grew, food preparation was moved to a central commissary at 202 S. Tenth Street, where board members tested menu items daily.

Philadelphia’s Automats catered to specific crowds: stevedores, who worked irregular hours, preferred the twenty-four-hour location at 234 Market Street; Jeweler’s Row merchants and Gimbel’s employees frequented 818 Chestnut; the Eleventh and Arch Automat “reserved” nightly a table for prostitutes; politicians and judges frequented 1508 Market Street; and insurance salesmen gathered at 6006 Market Street. By 1932, the company had forty-six restaurants in Philadelphia, of which fewer than half contained Automats. Including the company’s New York locations (the first appearing in 1912), by 1940 Horn and Hardart fed 700,000 people each day. The Automats’ “nickel-throwers,” women who gathered daily thousands of coins, became a citywide fascination.

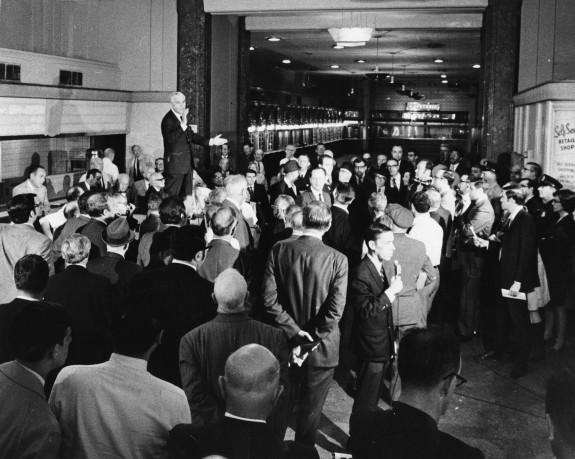

Following World War II and mass migration to the suburbs, the popularity of Automats in Philadelphia, which peaked during the Great Depression, waned. Fast food chains such as McDonalds developed drive-thru windows that served the region’s growing car culture. Trying to capture suburban customers, Horn and Hardart opened retail stores and cafeterias in Northeast Philadelphia, Jenkintown, Willow Grove, Havertown, and Wilmington, Delaware. Hoping to revive the Automats’ popularity, in 1961 they sought and received liquor licensing for their location at Sixteenth and Chestnut Streets. Yet competition and changing dining tastes as well as the company’s diversification, labor troubles, and expansion spelled trouble. Urban renewal also abetted the Automat’s demise. In 1965, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority forced Horn and Hardart to close their commissary to make way for Thomas Jefferson University’s dormitories. The following year, the Sixteenth and Chestnut building was demolished and replaced with a movie theater. In May 1969, the original Automat at 818 Chestnut Street was auctioned and its interior donated to the National Museum of American History. In 1981, Horn and Hardart filed for bankruptcy and many of its restaurant buildings were converted into McDonald’s, Burger King, and Gino’s Hamburgers, and other fast food outlets. Finally on May 12, 1990, Greater Philadelphia’s last Automat, located in Bala Cynwyd, shut its doors.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Rowan University, and Moore College of Art and Design. He has written for Buildings and Landscapes, Environmental History, Planning Perspectives, and other publications. He received his M.A. in history from the University of Nevada and his Ph.D. in history from Temple. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.