Campbell Soup Company

Essay

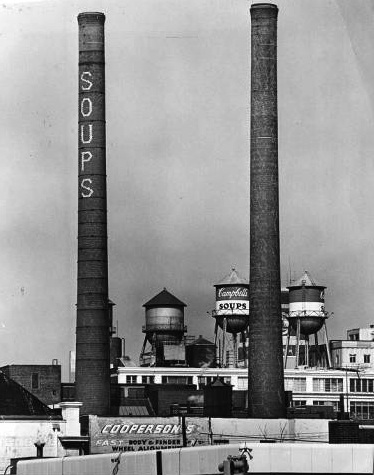

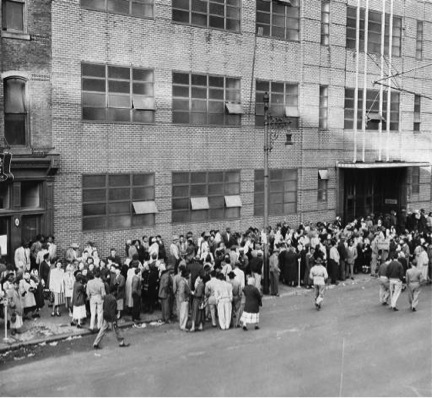

Anyone crossing the Benjamin Franklin Bridge from Philadelphia to Camden during most of the twentieth century saw one of the best-known icons of American consumerism, the giant Campbell-Soup-can water towers looming over the company’s flagship cannery. Campbell Soup may have been “America’s Favorite Food,” as the title of the company-sponsored history claims, but it was also much more to residents of the Delaware Valley. South Jersey’s farmers grew the tomatoes that went into the cannery, and at its height in the middle of the century it employed five thousand production workers year-round at its Camden plants. Thousands more high school students, housewives, and temporary workers newly arrived from Puerto Rico or elsewhere swelled the workforce at peak harvesting time. By 1991 no evidence of the cannery remained, though the company continued to maintain corporate headquarters in the city of its birth.

When a tinsmith and a vegetable merchant joined forces to form the Anderson & Campbell Preserve Company in Camden in 1869, there was little to differentiate their establishment from the dozens of other small canneries scattered among the towns and fields of South Jersey. But after the wealthy Dorrance family of Bristol, Pennsylvania, invested in the company and the young John T. Dorrance (1873-1930) carved out a new niche for the firm in convenience foods–condensed soup–it rapidly outpaced all other canneries in the region. Dorrance also aggressively experimented with new forms of advertising, placing placards in streetcars and ads in popular magazines, and later was among the first to advertise on radio (Amos ‘n’ Andy) and television (Lassie). Campbell Soup became one of the most recognizable brands in America. In painting American icons, Andy Warhol famously chose the Campbell Soup tomato can as his commercial subject.

A Focus on Detail

But sales and marketing were dependent on the continued availability of good-quality but low-cost products. Dorrance devoted extraordinary attention to controlling every detail in the production of his soups. He employed agronomists to develop the perfect seed for his tomatoes and dictated to farmers how much fertilizer to apply and when. In the soup factory Dorrance’s industrial engineers closely observed each task performed by workers, decreed the optimal procedure to be followed, and calculated the precise wage to be paid for each subtask. His efforts at “scientific management” and automation yielded impressive results. The Camden cannery turned out ten million cans per day during peak season and generated fabulous wealth for the Dorrance family.

The pressure to produce took its toll on the cannery workers. Employees labored long hours for low pay in hot, noisy, and often dangerous conditions, and their frustrations eventually erupted in a spontaneous strike in 1934. Workers succeeded in winning union recognition in 1940, and over the next several decades work stoppages and other industrial actions were regular features in area newspapers. The company countered by bringing in new sources of low-wage labor and by building canneries elsewhere. Although Camden and Chicago union locals won a united strike in 1946, an attempt at a multi-plant strike in 1968 eventually ended in failure.

End of Line for Camden Plant

When Campbell stopped using South Jersey’s famous tomatoes in 1979 in favor of industrially produced tomato paste from California, the company was free to move production to newer and, it hoped, less contentious rural plants. The last can rolled off the line in Camden in 1990, and the plant was imploded a year later.

Campbell Soup Company remained, however, an important corporation nationally and in the Delaware Valley. By continuing to aggressively cut costs and make innovations in its product portfolio, the company consistently delivered profits of about a billion dollars annually on sales of some eight billion dollars in the early twenty-first century. In Camden, where 1,200 white-collar employees continued to work at the firm’s world headquarters in an expansive campus setting, Campbell remained one of the region’s most important and visible local companies.

Daniel Sidorick has taught history at Temple and Rutgers Universities and the College of New Jersey. His book Condensed Capitalism: Campbell Soup and the Pursuit of Cheap Production in the Twentieth Century (Cornell University Press) was awarded the Richard P. McCormick Prize by the New Jersey Historical Commission. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History