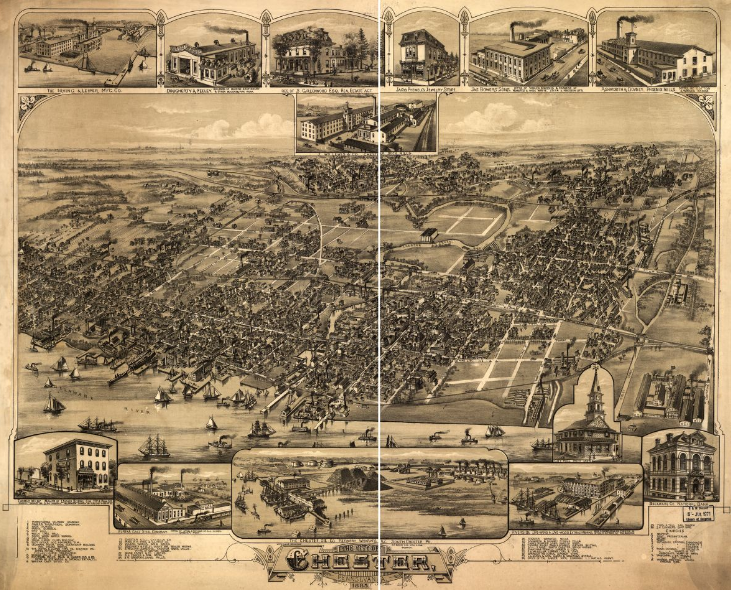

Chester, Pennsylvania

Essay

Located 30 miles down the Delaware River from Philadelphia, the small but once industrially mighty city of Chester emerged in the latter part of the twentieth century as but a shadow of its former prominence in the county and the region. The municipality’s fortunes shifted many times over the 334 years of its existence, evolving from a small Swedish settlement to the near-capital of the Pennsylvania colony to a neglected village to a manufacturing powerhouse and then into dire post-industrial decline.

Initially dubbed Upland when it was settled in the 1600s by Swedish and, then, Dutch traders who lost control of the area after the Anglo-Dutch War of 1674, the town was renamed Chester by William Penn, who rechristened the village upon his arrival in 1682. He held Pennsylvania’s first General Assembly there, and even tried to make it his capital. But when local landowners objected, Penn instead chose a site farther north that became Philadelphia. As a consequence, Chester remained a lightly populated village throughout the eighteenth century (although it remained the seat of what was then Chester County until it was split in 1789 to create Delaware County).

Chester finally began to grow in the 1800s, especially after the Civil War, establishing itself as the economic and social heart of Delaware County. Beginning in the 1870s, its working-class population swelled with Irish, Polish, Italian, and African-American migrants attracted by plentiful work along the waterfront (notably John Roach’s iron shipyards) and in the city’s textile industry. In 1889 the independent borough of North Chester amalgamated with the city, and South Chester followed in 1897, giving the city its present physical geography.

The early decades of the twentieth century cemented Chester’s status as a factory town, beyond textiles, with a burgeoning base in heavy industry. The number of industrial jobs tripled between 1910 and 1920 as new industries began to dominate the waterfront—most prominently in the form of the Pew family’s Sun Ship shipyard and Sun Oil Company (located in Marcus Hook). Among other notable industrial employers nearby were Scott Paper, Ford Motor Company, the Baldwin Locomotive Works, and Westinghouse Electric Company. The city’s population jumped by almost 20,000 people during this period to 58,030.

The Wild Side of Chester

The early twentieth century also established Chester’s reputation as a wild town, home to dozens of bars, brothels, drug dens, and gambling halls, with a thriving red-light district in the Bethel Court section. All of this activity was abetted by the local political machine, which won power with funds largely derived from organized vice while sustaining the loyalty of its constituents with patronage and social services. In addition to the daily pulse of vice and corruption, the city was periodically wracked by mass violence. A 1908 streetcar strike lasted from April through August and was punctuated by dynamite bombings, gunfights, and mob attacks. In the summer of 1917, during the peak of the wartime population boom, a series of race riots convulsed the city, featuring running battles between Black and white residents that resulted in twenty-eight shootings and seven deaths.

During the 1920s Chester contained roughly a third of Delaware County’s residents, but as the first wave of suburbanization occurred new population centers began to form on the western border of Philadelphia (especially Upper Darby). Still, the industrial and political heart of the county remained to the south. Even though Media had replaced Chester as the county seat in the mid-nineteenth century, Chester was home to the powerful Republican political boss John McClure. He ruled the city from 1907 until 1965, despite being sentenced, although not imprisoned, in 1933 for bootlegging. The machine’s power was near total, with his favored candidates easily winning elections with the help of police officers who served as political agents and payments made to those who voted Republican.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Pews’ industrial interests in and around Chester were the focal point of social and political tensions in the city. In 1936, the family offered control of employment at the shipyards and the oil company—which never suffered layoffs, even at the height of the Depression—as patronage to lure McClure out of his post-scandal retirement. The family wanted his help in defeating New Deal Democrats and their allies in the unions affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which were locked in bloody conflict with Sun Ship. The campaign culminated in the CIO-affiliated workers winning the right to unionize in 1943 after nearly a decade of organizing. After the beginning of World War II, as work at the shipyards increased by tens of thousands, Sun Ship became the largest private-sector employer of African Americans in the nation—even controversially segregating many of its Black workers into Yard No.4.

That influx of African-Americans, most of whom were the first to be laid off from industrial work after the war, and federal postwar housing and veterans’ policies that specifically excluded African-Americans, eventually transformed Chester into a majority-Black and impoverished island cut off from a more prosperous majority-white region. Even as the elite population largely decamped for the suburbs, the construction of Interstate 95 blatantly severed the poorest sections of the city from the surrounding area. In 1950, Upper Darby became the most populous municipality in the county, and over the following decade Chester’s population shrank for the first time. Although McClure continued to rule from a mansion in the city, where Richard Nixon visited him during the 1960 political campaign, his political machine increasingly drew its strength from the growing suburban townships.

Educational Desegregation

Within the city, African-Americans fought long, hard campaigns to desegregate public accommodations, public housing, and public education. The education campaign would not come to fruition until after 1964, when huge protest marches, sporadic violence, and a lengthy boycott of downtown merchants finally forced integration of the schools.

But these victories were bitter, as industry abandoned the city at the same time. In 1950 over 50 percent of the city’s workforce was employed by manufacturing firms, but by the early 1960s many of the area’s biggest employers had already closed, including Baldwin Locomotive and Ford. Sun Ship dramatically downsized to 4,000 workers from a peak of 35,000 during the Second World War. Plentiful jobs could be found in the suburbs, but most of the surrounding municipalities bitterly, and successfully, resisted attempts by Chester’s African-Americans to move closer to employment opportunities.

By the 1980s Chester was a city bereft of industry, although the Crozer-Chester Medical Center and Widener University remained in the city. (The Crozer Theological Seminary, which Martin Luther King Jr. attended, left Chester in the early 1970s.) Saddled with the remnants of McClure’s Republican machine numerous bottom-rung projects opened in Chester, including a trash incinerator, a sewage treatment plant, and a prison. McClure’s mansion became a substance abuse treatment center. More promising, it seemed, were the arrivals of Harrah’s Casino in 2007 and the PPL Park soccer stadium in 2010. Despite their potential for spurring further development, that prospect was compromised by a scarcity of full-time jobs for local residents and the separation of these institutions from the city by a large road and vast parking lots. The school district was intermittently run by the state, and close to half the students attended charter schools, innovations that did nothing to improve the district’s abysmal performance or sustained budget crises. Chester’s downtown was largely abandoned, its neighborhoods scarred with blight, and the population in 2010 roughly half the 1950 number.

Jake Blumgart is a reporter, editor, and researcher based in Philadelphia. He is a contributing writer at Next City and Flying Kite. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Controversial choice to turn Chester Upland schools around (WHYY, August 20, 2012)

- Food desert no more, Chester welcoming first grocery store in years (WHYY, September 27, 2013)

- Chester city government battles 'epidemic' violence (WHYY, July 3, 2014)

- Harrah's Casino an economic boost, but not a cure, for ailing Chester (WHYY, July 22, 2014)

- Crozer-Chester nursing strike continues into day two (WHYY, September 22, 2014)

- A park? A bench? Chester gets grant to crowdsource ideas for beautifying downtown (WHYY, May 11, 2016)

- Chester, a city working on a new narrative (WHYY, September 28, 2016)

Links

- Baldwin Locomotive Works Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Francis D. Tyson, on the 1917 Chester Race Riots, 1919 (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Pearls Of The Delaware (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- African American residents of Chester, PA, demonstrate to end de facto segregation in public schools, 1963-1966 (Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College)

- Chester Artists Revitalizing Corridor on Their Own Terms (Next City)