Child Labor

By Maia Silber

Essay

Young people have worked as long as families’ expenses have exceeded adults’ incomes. In the Philadelphia region’s preindustrial, industrial, and postindustrial eras, children sought work for the needed earnings it brought them and employers sought children for the lower pay they commanded. But the nature of youthful occupations changed along with the economy, and so too did attitudes about the employment of minors. Over the course of three centuries, local policymakers and the public alternately condemned children’s work as a consequence of poverty and a mechanism of exploitation, and encouraged it as a means of alleviating poverty and inspiring virtue.

In eighteenth-century Philadelphia, the children of working families sold twigs for fuel, tended cattle, cleaned chimneys, hauled dairy products from the countryside, and apprenticed themselves to craftsmen. State coercion, as well as economic necessity, drove poor children to work in an era when most authorities saw youthful employment as a means of combating dependency and vice. Under the system of “pauper apprenticeship,” local magistrates could require destitute families to “bind out” children to households that would provide for their maintenance and sometimes education in exchange for their labor. Meanwhile, enslaved children—about a third of the colonial city’s total enslaved population was under the age of twelve —were forced to work in occupations ranging from domestic service to craft trades.

When Philadelphia emerged as a leading industrial city in the mid-nineteenth century, children made up a significant minority of its labor force. Entire families wove cloth with simple handlooms and performed other outwork in the cottage industries that coexisted with the new factories into the 1850s. And when adults went to work for wages in the mills, they brought their children with them. An investigation conducted by the Pennsylvania Senate in 1837 found that about one-fifth of the state’s cotton workers were children under the age of twelve.

It was the mass entrance of children into factories that inspired the early movement to regulate what was first labeled “child labor.” Protestant revivalist millhands in Manayunk petitioned Pennsylvania lawmakers for a minimum age of employment of 12 and a ten-hour day for all workers. After a protracted legislative debate, the law that finally emerged banned children under twelve from working in cotton, woolen, silk, and flax mills, but permitted children over fourteen and adults to work longer than fourteen hours through “special contracts.”

Beyond Factory Work

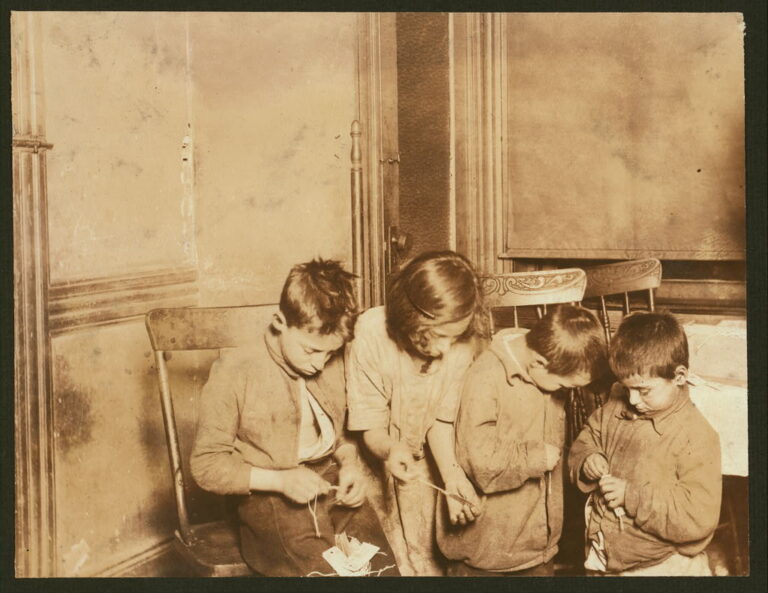

Nineteenth-century Philadelphians defined child labor as full-time, wage-earning, and specifically industrial employment for minors under the age of twelve or fourteen. Yet children also continued to work outside of factories and even outside of the formal economy after industrialization. The incomes that children earned from peddling and other “street trades” provided a crucial source of support when injury, illness, or a bout of cyclical unemployment resulted in the loss of adults’ wages.

The industrial focus of reformers persisted as child labor reform became a full-fledged movement in the early twentieth century. “That the industrial pursuits of to-day are, with all their efficiency and prosperity, attended by certain deplorable conditions, most of us recognize,” wrote the editors of one pamphlet distributed at a 1906 Philadelphia exhibition on contemporary social problems. Of the conditions that concerned the exhibition’s organizations—crowded tenements and the communicable diseases that spread within them, the low wages and long hours that characterized “sweated” work—none provoked as much moral outrage as “that great and spreading menace,” “child labor.” The exhibition’s organizers and participants included the Eastern Pennsylvania Child Labor Committee (an affiliate of the National Child Labor Committee), the Consumers’ League of Philadelphia, and the White-Williams Foundation, three of the leading groups devoted to the issue.

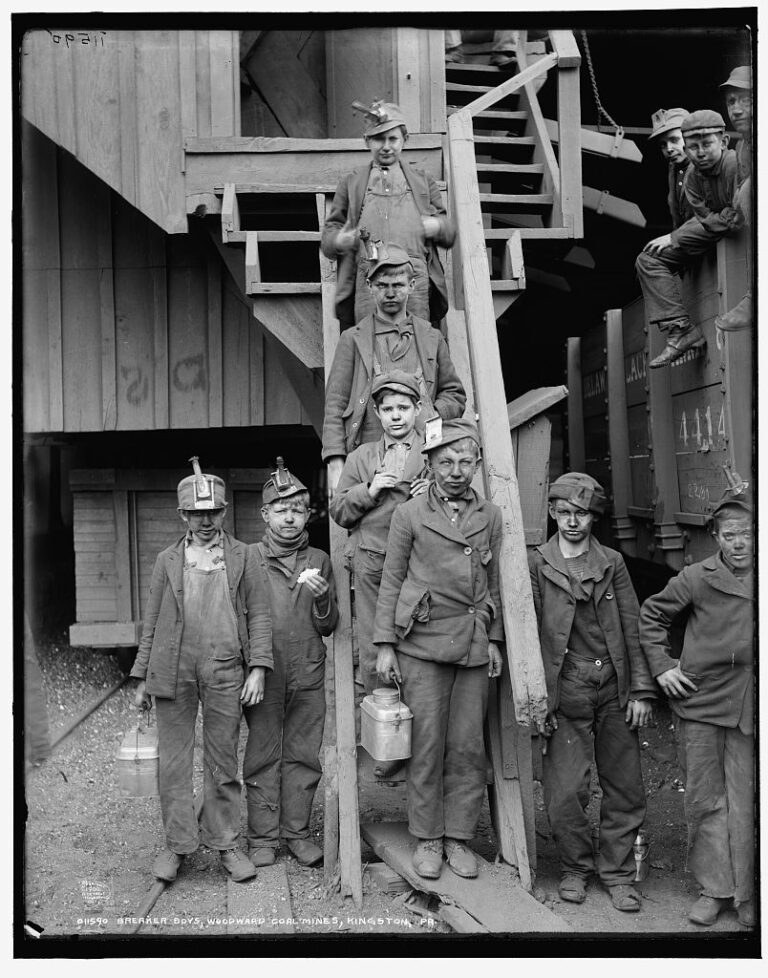

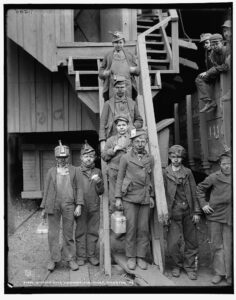

Child labor—typically defined in the Progressive Era as waged employment for minors under sixteen—was a concern of Progressives nationwide, but local reformers had particular cause for alarm. In 1900, Pennsylvania counted more children under the age of sixteen employed than any other state with the exception of Alabama. As the pace of mechanization, urbanization, and immigration accelerated, employers sought “little people” for “little pay” in nearly all of the major industries of Philadelphia and its environs: from the “cracker-off boys” who broke the cooling glass from the end of the blowpipe in glass factories, to the “breaker boys” who separated impurities from anthracite coal by hand, to the “bender-up girls” who folded the edges of pre-scored cardboard in paper box factories. As late as 1924, the city’s famous textile mills employed more than half of all children who worked in manufacturing establishments, according to one study based on more than three thousand employment certificates.

Like other turn-of-the century Progressive Era reform movements, the women-led campaign against child labor directed maternalistic concern for the plight of the vulnerable toward the end of state regulation of industry. Organizations such as the National Consumers League and its local affiliates leveraged women’s control over household budgets, urging shoppers to boycott companies known for the employment of children and other abuses.

Resistance to Reform

Seeking to protect children from the hazards of industrial labor, Progressive Era reformers encountered opposition not only from employers but also from working-class parents who relied on children’s incomes. Young people themselves often associated labor with autonomy and pride rather than danger. Those attitudes shifted gradually over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in concert with the rise of compulsory schooling and new forms of recreation, the automation of many unskilled youthful jobs, and the increasing physical risks of employment in the industrial workplace. By the time the NCLC celebrated its tenth anniversary in 1914, the District of Columbia and thirty-seven states, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, had passed laws establishing a minimum age of employment.

Pennsylvania’s law, passed in 1909, prohibited employing children under sixteen in mines, children under fourteen in other manufacturing and commercial settings, and boys under twelve from selling goods in public places (girls were prohibited from peddling in 1901). Although a 1915 revision to the law extended a minimum employment age of fourteen to all establishments, agriculture and domestic service were still exempted. The law’s varying standards reflected the long-standing focus of reformers on the abuse of child labor in mills and mines. After all, these were establishments that employed children in particularly dangerous conditions: two in every ten accidents to working children in Pennsylvania occurred in anthracite and bituminous coal mines, where children operated heavy machinery in underground shafts.

But laws enforced by factory inspectors did little to regulate labor performed outside of the workplace. Employers of “errand boys”—the most common occupation for the Black male children whom manufacturing employers typically discriminated against— easily escaped state supervision. And despite the 1922 extension of the state’s child labor laws to industrial home work, common among eastern and southern European immigrant families, one 1926 study found that half of all home-working households in Philadelphia and surrounding counties still included an illegally employed child.

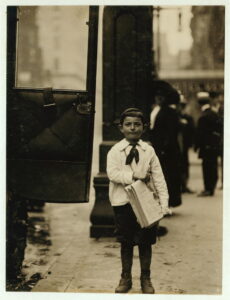

Likewise, reformers found that the law had little effect on the “street trades.” Scott Nearing (1883-1983), an economist and secretary of the Pennsylvania Child Labor Committee, attributed what he saw as an epidemic of moral vice among working-class boys working late nights in unwholesome places to “newsboy-ism.” Even as newspaper sellers became critical to the operations of rapidly consolidating commercial newspapers, publishers claimed that their young charges were not their employees at all but rather “little merchants” engaged in entrepreneurial endeavors of their own.

Outside the City Limits

Reformers became even more alarmed when they turned their attention to child labor outside of the city limits. In 1923, Janet McKay (1881-1959), a field worker for the Public Education and Child Labor Association of Pennsylvania, investigated the seasonal migration of Philadelphia families, mostly Italian, to New Jersey truck farms and cranberry bogs. Boys and girls as young as twelve scooped berries by hand from the bogs, carried sacks of fruit to the roadside for sale, and drained ditches. Employers in rural canneries also relied on the transiency of their workers to evade compulsory education that did not apply to interstate migrants. Cannery investigators in 1926 identified 250 underage children skinning tomatoes and husking corn during school hours in forty-one canneries, but estimated that the true number was higher. Many “little figures” simply fled into the woods when the state officials arrived.

By the 1920s, Philadelphia reformers were increasingly convinced that even the strictest state legislation was not only inadequately enforced but flawed in its design. After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned two federal laws that would have regulated child labor on a nationwide basis, they launched a campaign for a constitutional amendment. Passed by Congress in 1924, the Child Labor Amendment would have given the federal government the power to regulate and prohibit the labor of persons under eighteen years of age, in any industry—reflecting the movement’s adoption of a far more expensive definition of child labor than ever before.

But as the proposed twentieth amendment moved to the states for ratification, its opponents launched a campaign for its defeat. In Pennsylvania, newly formed groups such as the Republican Women of Pennsylvania and the State Council of Pennsylvania Order of Independent Americans had industry ties but mobilized grassroots support. A coalition of manufacturers, rural farmers and working-class urban Catholics—who feared that the amendment would license government interference with religious education—characterized the federal regulation of child labor as an undue and “socialistic” encroachment on the traditional autonomy of the family and household.

Pennsylvania and New Jersey both effectively rejected the amendment in the initial push in 1925, and then joined twelve other states that finally voted to ratify it in 1934 amid Depression-era pressures to reduce labor-market competition. But by then, national policymakers had turned their energy toward passing child labor reforms as part of New Deal recovery efforts. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA, 1938) exempted children involved in agriculture, service, communication, transportation, and the street trades—some four-fifths of all working youth, the very same majority also exempted by Pennsylvania’s and other state laws.

With War, a Shift in Attitude

While the Child Labor Amendment languished in state legislatures, the nation’s entrance into World War II dramatically increased the demand for young workers. Employers across industries faced a tight labor market, and state legislatures acceded to their pressure to relax regulations to meet the demands of wartime production. Pennsylvania passed laws increasing the maximum hours and lowering the minimum age requirements for minors who worked “directly or indirectly in furtherance of the war effort,” while New Jersey’s 1942 Student Service Act allowed school officials to relax attendance requirements for youth working as agricultural laborers. Over the course of the war years, the number of Pennsylvania children who annually left school for work increased from 19,143 to 118,655.

The exigencies of wartime production enabled employers and sympathetic policymakers to recast child labor as a patriotic necessity. Farmers in southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey recruited teenaged day haulers transported on trucks between public schools in Trenton and work sites in its rural environs. Through its Victory Farm Volunteers program, the federal government recruited high school students for farm employment marketed as a wholesome and healthful experience for poor urban youth who otherwise lacked opportunities for outdoor recreation.

Laws and standards changed to meet the wartime emergency had a lasting effect, even in industries that never had much to do with defense. A year after the war ended, Philadelphia’s bowling alleys still routinely employed “pin boys” under the age of fourteen, often in violation of state labor laws. Agriculture remained the greatest offender through the postwar years. In 1961, an undercover journalist found children under ten carrying 100-pound potato sacks on a farm in Hastings, New Jersey. A 1949 amendment to the FLSA prohibiting agricultural employers from employing children during school hours didn’t interfere with their labor, performed between 3 p.m. and midnight.

New Focus in the 1950s

Though the Consumers League of New Jersey and other reform organizations continued to advocate for regulating migrant agriculture, the campaign against child labor shifted its focus in the 1950s. In 1959, the NCLC changed the name on its letterhead to the National Committee on Employment of Youth (NCEY).

The organization defined its new focus as the promotion of opportunities for vocational education, job training, and part-time and summer employment for poor urban youth. As an exemplary model, the organization cited the Philadelphia School-Work Program, which allowed high school students to work for part or attend job-training sessions for part of the school day. Similarly, the Philadelphia Youth Conservation Corps encouraged boys to leave school early for temporary work assignments clearing brush, removing parasitic vines, and chopping dead trees in the Fairmount Park.

Progressive Era reformers fighting for a Child Labor Amendment had sought to increase the ages and expand the list of occupations that fell under the category of “child labor.” Their postwar counterparts now redefined teenagers’ part-time work as “youth employment.”

The Twenty-First Century

In July 2022, the New Jersey General Assembly voted to pass a bill increasing the number of hours that minors in the state can work and eliminating a requirement for children to obtain a separate work permit for each job they seek. The state legislators who proposed the bill pitched it as an emergency remedy to the service industry’s post-COVID pandemic labor shortage. Days before the vote, U.S. Labor Department investigation had found that the Manasquan-based business Jersey Mike’s Subs employed 14- and 15-year-olds beyond permitted hours. “With all the real problems threatening the future of this country’s survival, they’re going after a sub shop that employs teenagers,” lamented one local radio host.

The nature of minors’ employment changed over the years since twelve-year-olds accompanied their parents to the mill. But just as importantly, so did understanding of who counts as a child and what counts as labor. Those categories expanded and contracted across contexts of industry, service, and agriculture; during times of peace, war and pandemic; in the summer and after school. The kids are still at work.

Maia Silber is a PhD candidate in American history at Princeton University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- An Illustrated Handbook of the Industrial Exhibit Held Under the Auspices of the Pennsylvania Child-Labor Committee (1906)

- Armstrong Association of Philadelphia, A Comparative Study of the Occupations and Wages of the Children of Working Age in Potter and Durham Schools, Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Board of Education, 1913.

- McKay, Janet S. Pennsylvania Children on New Jersey Cranberry Farms. Philadelphia: Public Education and Child Labor Association of Pennsylvania, 1923.

- Evans, Eileen F., Lauder, A. Estelle, and McConnell, Beatrice, Accidents to Working Children in Pennsylvania in 1923. Philadelphia: Consumer’s League of Eastern Pennsylvania, 1925.

- Griscom, Anna Bassett. The Working Children of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: White-Williams Foundation, 1924.

- Bureau of Women and Children, “A History of Child Labor Legislation in Pennsylvania,” Department of Labor and Industry Special Bulletin No. 27

- Fairchild, Mildred and Kindred, Leslie, “Child Labor inn Pennsylvania,” The Bulletin of the National Association of Secondary School Principals 30.137 (1946)

- Wright, Dale. “The Forgotten People,” New York World-Telegram 10 October 1961- 23 October 1961

- Benjamin, Judith G, Freeman, Marcia K., and Lash, Seymour. Youth Employment Programs in Perspective. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1965.