Cholera

Essay

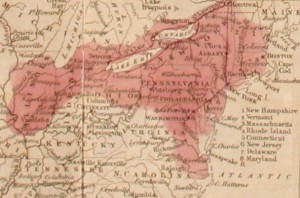

The cholera epidemics that struck Philadelphia in 1832, 1849, and 1866 provided a catalyst for transforming the health and hygiene standards of the city. Asiatic cholera, endemic to India, escaped the sub-continent in 1817. It reached Western Europe in 1831, and was carried to North America in 1832 aboard immigrant ships, breaking out in Philadelphia in July of that year. The disease is characterized by extreme pain and dehydration from violent diarrhea and vomiting, often leading to death.

The prestigious College of Physicians of Philadelphia, dominated by sanitarians, presumed it was not a new disease but an “epidemic phase” of indigenous summer diarrhea caused by miasmic vapors emitted from the ever-present filth in nineteenth-century cities. Rejecting the theory that cholera was spread by contagion, the fellows of the college believed predisposing conditions made the poor, the profligate, the immoral, those with weak constitutions, and especially certain ethnic groups, the most likely victims of the disease. To combat the epidemic, they advised the Board of Health to clean the city of filth, set up local hospitals, and educate the populace to avoid dangerous foods and habits they believed led one to be susceptible to the disease. These recommendations were put into effect when cholera broke out in the city in July 1832. Meanwhile, to help the afflicted private charity and church groups provided nurses and places for recovery. The Catholic church especially responded to the challenge of aiding the Irish and other Catholic immigrants, with some nuns coming from as far away as Emmitsburg, Maryland, to meet the crisis. By mid-September the epidemic had run its course, leaving a death toll of 935.

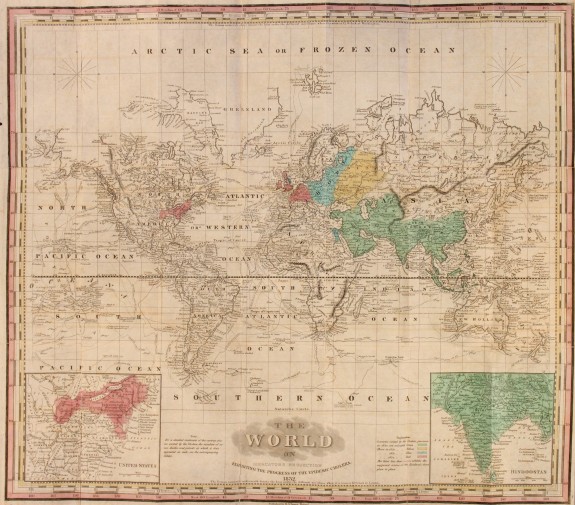

Far in excess of 141 deaths took place in the state-owned Arch Street prison and the city almshouse where inmates suffered from overcrowding, appalling hygienic conditions, and generally poor health, which the fellows of the College of Physicians saw as proof of the validity of their theory of the etiology of the disease. In an attempt to stop the carnage at the prison, the authorities released inmates who had not been convicted of major crimes. Many fled to Chester, Berks, Lancaster, and other neighboring counties, spreading cholera as they went. Citizens fleeing the city also spread cholera to surrounding areas.

Philadelphia’s Lower Death Rate

Philadelphia’s death rates were one-quarter those suffered in New York City and one-twelfth those of Montreal. Medical authorities attributed the city’s good fortune to the use of water from the Fairmount Reservoir to cleanse filth from the streets, inspiring cities such as New York and Boston to create municipal water supplies modeled on that of Philadelphia. Unbeknownst to the medical profession, the disease was caused by a bacterium and was spread primarily through feces-contaminated drinking water. It was not clean streets but drinking water from the reservoir, uncontaminated by the cholera bacilli, which accounted for the city’s low death rates. In the Black and Irish districts south of South Street, the death rate from cholera was three to four times greater than in the city. While the College of Physicians attributed these deaths to the poverty and “racial” character of the population, in reality, these areas had very limited access to Fairmount drinking water and consequently suffered far more affliction than those with such resources.

Cholera returned to Philadelphia in 1849. Despite a 50 percent increase in population, only 747 people died from the disease. Medical officials again concentrated on eliminating filth and building neighborhood hospitals, but in fact this radical reduction in the death rate from cholera was due primarily to the expansion of the Fairmount water system. Again the largest concentration of deaths was in the almshouse, where at least 228 died. Lesser cholera outbreaks occurred from 1850 through 1854.

Evidence Points to Contagion as Cause

Although fellows of the College of Physicians continued to advocate the miasma theory at mid-century, doctors trained in the city were challenging its validity. In Columbia, Lancaster County, 75 miles west of the city, cholera broke out in September 1854, killing at least 127 people. Immigrants traveling west from Philadelphia on the railroad brought the disease to the city. Dr. T. Heber Jackson, of Philadelphia, attended victims and concluded that transmission of the disease was best explained by contagion, not miasma. He also questioned the prevailing belief in predisposing causes, pointing out the disease had struck rich and poor, Black and white, alike.

Philadelphia-trained Dr. John Atlee of Lancaster reinforced this criticism. He observed that an outbreak of cholera in Lancaster in the summer of 1854 had not developed spontaneously but had been brought to the city by infected people and spread by contagion. His discovery of microscopic particles in the effluvia of the Lancaster cholera victims gave credence to the germ theory that soon become medical orthodoxy. The analyses of these two physicians mirrored the research linking cholera to polluted water being done by Dr. John Snow of London. Although their work remains little known, it is illustrative of the richness of medical research and enquiry in mid-nineteenth-century Philadelphia.

Lesser cholera outbreaks occurred in 1866, 1891, and 1899. While many in the city’s medical community still advocated the miasma theory in 1866, they had come to believe that the disease was also spread by contact with fluids emitted by the victims. The Board of Health’s use of disinfectants greatly reduced deaths during that epidemic and marked another major step towards the acceptance of the germ theory of medicine. Typhoid epidemics and recurrences of cholera in the 1890s led the Board of Health to install water filtration systems for the city. No subsequent outbreaks of cholera occurred after the city expanded and improved sewage disposal and water treatment in the twentieth century.

John B. Osborne is an Emeritus Professor of History at Millersville University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2010, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History