Co-Working Spaces

Essay

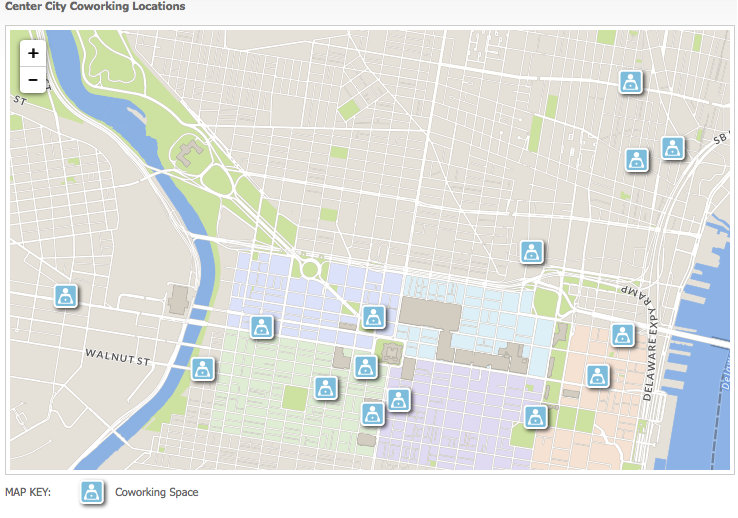

In the 2000s and 2010s, nearly thirty co-working spaces opened in the Philadelphia area. Co-working offered flexible, shared office facilities to freelancers, technology start-ups, entrepreneurs, and nascent businesses that did not require or could not afford private workplaces. These spaces were designed to foster a collaborative atmosphere, where clients could share innovations and resources. A related type of facility—so called “maker spaces”—offered artisans and small-scale manufacturers communal access to industrial equipment at a low cost. By 2015, co-working spaces occupied 190,000 square feet of office space in Center City. Several spaces were located in outlying neighborhoods like Fishtown and Kensington, and still others operated in Philadelphia’s suburbs.

Co-working was part of Greater Philadelphia’s broader transformation from an industrial to a post-industrial economy. In the late 1970s, the number of jobs in management, service, and technology-based sectors surpassed manufacturing for the first time. The co-working model was created to accommodate this new breed of post-industrial worker. Mostly well-educated, the majority worked in new media, technology, or creative fields. While some were recent college graduates, many were middle-aged: In 2015, the median age for Philadelphia’s 30,000 to 35,000 freelancers and self-employed workers was 47. An increasing reliance on technology freed these workers from traditional office arrangements. Entrepreneurs and freelancers needed little more than a laptop and an Internet connection for their jobs. Others were part of the growing ranks of Americans working from home, a figure that increased 37 percent from 1997 to 2010. Even if they were freed from commuting to offices, some sought part-time conference space for client meetings. And many yearned for the sense of community and collaboration that conventional offices had offered.

In 2007, Philadelphia’s first co-working space, Old City’s Indy Hall, opened to meet the demands of this growing sector of post-industrial workers. Like many co-working spaces, Indy Hall moved into a renovated loft building—a repurposed industrial-age relic with a flexible open-plan interior. Co-founders Geoff Di Masi (b. 1970) and Alex Hillman (b. 1983) designed Indy Hall to offer a sense of community for Philadelphia’s freelancers and tech-industry workers. Hillman believed that workers would flock to Indy Hall “because they [were] lonely and unproductive in isolation.” In order to encourage cooperation, Indy Hall hosted after-hours parties and art shows.

Encouraged by the success of Indy Hall and buoyed by the growth in creative and tech-based fields, other co-working spaces soon opened in Philadelphia. Their business models diversified to appeal to different types of workers. Some, like the South Philly Co-Op Workspace, filled storefront spaces with neighborhood freelancers and small-business owners. Benjamin’s Desk, near Rittenhouse Square, pursued a more traditional corporate market, attracting architects, digital advertisers, and web designers. In Old City, The Hive (later closed) was the first co-working space exclusively for women entrepreneurs. Tribe Commons in Midtown Village promised co-working “rooted in Jewish cultural values.” Culture Works Greater Philadelphia offered a hybrid model, with rentable office space, mentoring, and philanthropic support for emerging arts and culture organizations.

Some co-working spaces provided more than desks and an Internet connection. So-called “makers’ spaces” offered artists, fabricators, and manufacturing startups shared access to expensive equipment. Makers’ spaces occupied formerly abandoned industrial buildings, capitalizing on Philadelphia’s rich history of manufacturing. Dr. Evan Malone founded NextFab, the first of these spaces, in the University City Science Center in 2009 as a “gym for innovators.” Malone hoped that his design and fabrication space would “help counteract the extensive offshore outsourcing of U.S. manufacturing and decline of manufacturing education and knowledge-base.” In 2012, NextFab moved into a renovated industrial space on Washington Avenue, where it offered its members access to welding, 3-D printing, wood milling, and computer-controlled machining equipment. Similar makers’ spaces followed. A 250,000-square-foot space, the Loom at Richmond Mills, opened in a converted textile mill at Frankford and Allegheny Avenues. The Sculpture Gym in Kensington, started with a $20,000 grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation’s Arts Challenge, provided shop facilities and training for artists working with wood, metals, and ceramics.

In the 2010s, co-working spread to Philadelphia’s suburbs. HeadRoom ran a 3,000-square-foot office space in Media in Delaware County. Kings Hall converted three adjacent historic buildings into a co-working space in downtown Haddonfield, New Jersey. Other suburban co-working spaces, however, struggled to attract enough workers. In November 2012, Business Casual Coworking opened in Bristol, Pennsylvania—but it quickly shuttered. Phoenixville’s Skylight Coworking opened in 2012; one year later, it moved and rebranded as the Dream Factory. Ultimately, it was unclear if suburban towns had the density of independent workers and start-ups to support the co-working model.

Closures were not limited to the suburbs. Several co-working spaces in Philadelphia folded in the 2010s. The Transfer Station, which opened in 2013 in a former retail space on Main Street in Mannayunk, quickly closed; its plans to reopen in a second location also fizzled. The space known as 3rd Ward, which had operated a successful co-working space in Brooklyn, New York, opened a 27,000-square-foot co-working and events space in Olde Kensington in 2013. But it unexpectedly ceased operations later that year, citing high operating costs. (Its original Brooklyn site also folded.) Other co-working ventures remained open but were forced to change their business models when faced with funding shortfalls. CityCoHo, at Twenty-Fourth and Walnut Streets, shifted from a communal space for individual workers towards private offices for more established companies. When it opened in 2015, Industrious followed CityCoHo’s model, devoting most of its 21,000 square feet at South Broad and Chestnut Streets to private offices.

In spite of these closures and worries about oversupply, co-working spaces continued to open in the 2010s, offering low-cost office space to a growing number of start-ups and technology-focused companies. By 2015, there were twenty-five spaces within Philadelphia alone. While the Philadelphia area’s transition to a post-industrial economy was by no means complete, co-working spaces intimated what that future might look like: decentralized, tech-driven, flexible, and helmed by well-educated workers.

Dylan Gottlieb is a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University where he works on recent American urban history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University