Diners

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

With its origins in late-nineteenth-century street vending and transient “quick lunch” operations such as horse-drawn food carts, the diner emerged as one of the most popular and successful restaurant genres in the United States. Although diners entered a period of protracted decline after World War II with the arrival of fast food restaurants, changing consumer tastes, and patterns of suburbanization, they also experienced later periods of rebirth and cultural nostalgia in both cities and suburbs. Many of the Philadelphia area’s diners, which once numbered several dozen, survived into the early twenty-first century or were refurbished with new concepts.

The birth of the diner is traced to Rhode Island, where in the 1870s, a vendor named Walter Scott parked his food cart in front of the offices of the Providence Journal. Noticing that night shift workers had few dining options (the city’s restaurants closed by 8 p.m.), Scott initially sold sandwiches, pies, and coffee from his “pioneer wagon” and later added hot dogs, oyster stew, and egg dishes. By the late 1880s, other operators expanded the concept throughout New England and as far west as Denver, Colorado. To accommodate more customers and comply with health and zoning regulations, by the 1890s quick-lunch operations became permanent, around-the-clock establishments, with many shaped like railroad dining cars. “White House Cafés,” with their frosted glass and artistic embellishments, made by T.H. Buckley Co. in Worcester, Massachusetts, set new standards for cleanliness and efficiency. By 1900, the firm had built and shipped more than 275 units around the country.

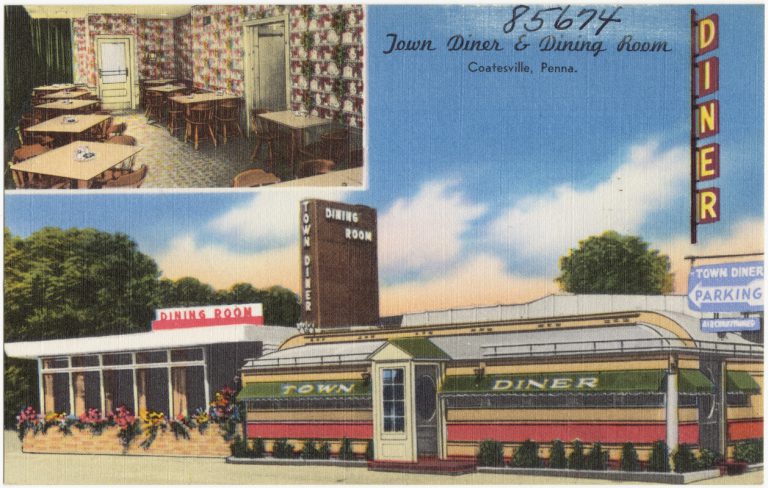

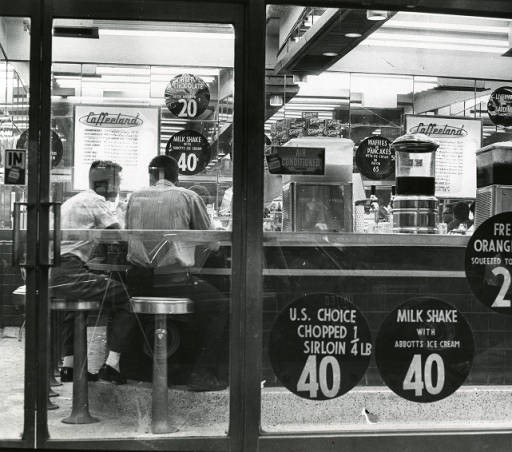

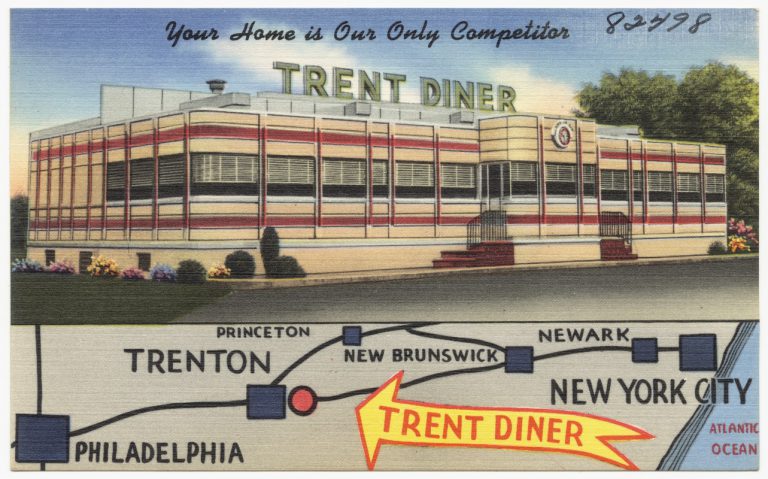

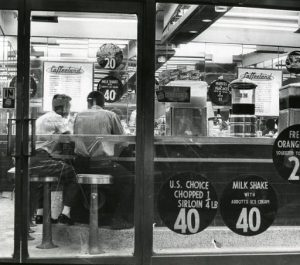

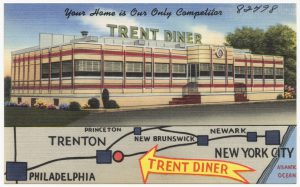

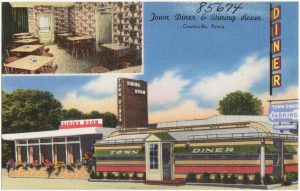

Diners continued to thrive during the 1920s as the nation basked in postwar economic prosperity. In 1924 a T.H. Buckley competitor, the Jerry O’Mahony Company based in Bayonne, New Jersey, became the first manufacturer to employ the term “diner,” shortened from “dining car,” in its sales catalog. Over time, New Jersey hosted several diner manufacturers, including the Silk City Co., the Mountain View Co., the Paramount Co., and the Fodero Co. Though located mainly in the northern portion of the state, these builders assembled many of the diners that appeared in greater Philadelphia by the end of the 1920s. In 1927, the Philadelphia-based J.G. Brill Co., then the world’s largest streetcar builder, opened a diner manufacturing division; its “Brill Steel Diners” rolled off the assembly line at one unit per week. Diners in this period were far larger than those built by the industry’s pioneers and contained stainless steel counters and tiled floors and walls to promote cleanliness. Most, such as the Mayfair (established 1926), the Melrose (1935), and the Ace (1936) operated in close proximity to factories and other industries in Philadelphia and Camden. Others, including Kennett Square’s O’Mahony-built Creekside Diner (c.1928), opened in small rural towns. During the Great Depression, as more expensive restaurants suffered declines in business, diners thrived due to their affordable fare and wide variety of menu items. Attempting to match diners’ appeal, in the 1930s a number of Philadelphia’s opulent hotels, including the Bellevue-Stratford and the Stenton, closed their luxury dining rooms and opted for cheaper “lunch counter” fare.

After World War II, with the onset of the Baby Boom and a healthy economy, the diner industry experienced impressive growth. Into the 1960s, companies such as Fodero continued to manufacture new units, including Philadelphia’s Broad Street Diner, the Red Robin Diner in Mayfair, and Old City’s Continental. Some, including the Mayfair, enlarged their spaces and exchanged their stainless steel aesthetic for stone, stucco, or brick. With increases in car ownership and large-scale suburbanization, diners appeared in areas beyond the region’s urban centers. Nowhere was the postwar diner more ubiquitous than in New Jersey, which contained not only the nation’s highest concentration of diner builders but also more diners and highways, per capita, than any other state. From the 1950s through the mid-1960s, dozens of new diners opened in South Jersey, including the Salem Oak in Salem (established 1955), Olga’s in Marlton (1959), Angelo’s in Glassboro (1964), the USA Country Diner in Windsor (1964), and Ponzio’s in Cherry Hill (1964). Philadelphia’s suburban towns saw several new diners, including Hank’s Place in Chadds Ford (1948), which became a favorite haunt of artist Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009); Downingtown’s Cadillac Diner (1954), where scenes for 1958’s The Blob were filmed; Upper Darby’s Llanerch Diner (1968), which appeared in the 2012 film Silver Linings Playbook; and the Sun Gate Diner (1959) in Marcus Hook. Wilmington, Delaware, and its environs also became home to many postwar diners such as The Charcoal Pit (1962) and Lucky’s Coffee Shop (1965), both located on the heavily trafficked Concord Pike (U.S. 202).

By the 1970s, many of the region’s diners closed due to declining business and the retirement of owners. Others survived but felt shopworn when compared with national chains, fast food outlets, and shopping mall food courts. Yet during the 1980s and 1990s, diners enjoyed a nostalgia- and kitsch-fueled revival as consumers rediscovered them. In 1987, the original Melrose, after having moved in 1959 from south Philadelphia to Robbinsville, New Jersey, was selected by the Smithsonian as representative of the American diner; due to exorbitant costs, the museum’s proposal to move the structure to Washington as an exhibit was shelved the following year. Influenced by the success of San Francisco’s upscale Fog City Diner (established 1985) and the Empire Diner in Manhattan, entrepreneur Stephen Starr (b.1956) in 1995 purchased and reopened the Continental Diner in Philadelphia’s Old City as a global tapas restaurant and cocktail lounge. Three years later, Starr opened his successful Jones near Jewelers Row, a diner-inspired comfort food establishment with retro-1970s décor.

In the early 2000s, as some neighborhoods declined or changed demographically, their long-operating diners closed. Several were owned by Greek immigrants who arrived in the region after World War II. Olga’s, owned by the Stavros family since 1959 and once hailed by the Newark Star-Ledger as the “queen of south Jersey diners,” closed in 2008 due to redevelopment plans while the Country Club Diner in Voorhees, New Jersey, owned and operated for fifty years by the Kokolis family, shuttered in 2011. Philadelphia’s West Oak Lane Diner closed in 2011 after a fire, the Aramingo Diner in Port Richmond reopened as an urgent care clinic, and the American Diner in West Philadelphia was renovated in the 2010s as Kabobeesh, an Indian-Pakistani eatery. Other area diners adapted to changing tastes, such as Geet’s in Williamstown, New Jersey, which expanded to include a sports bar with flat-screen TVs.

While Greater Philadelphia’s diners changed significantly since their introduction in the 1920s, their transformations over several decades demonstrated a certain flexibility that reflected customers’ cultural, culinary, and residential preferences. Having evolved from the food cart and rail-car styles, diners by the 2010s catered to urban, suburban, and shore town residents while still maintaining elements of affordability, efficiency, and popularity.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University, Moore College of Art and Design, and the Pennsylvania State University-Abington. A contributor to numerous books and journals, he is currently at work on a project about the history of Puerto Rico’s Levittown community. He received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Back in business: Broad Street Diner reopens (WHYY, December 27, 2011)

- Farm-to-fork trend challenging the traditional diner menu in South Jersey (WHYY, March 30, 2012)

- 'Silver Linings Playbook' draws diners to special booth at Llanerch (WHYY, January 10, 2013)

- Diner featured in Silver Linings Playbook novel damaged by fire (WHYY, June 2, 2014)

- Eagles defensive end Brandon Bair visits Trolley Car Diner (WHYY, January 9, 2015)

- A sampling of Philly's distinctive diners (WHYY, September 2, 2015)

Links

- The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia's Diners (HiddenCity Philadelphia)

- J.G. Brill Company Photographs (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Mt. Airy residents reflect on Trolley Car Diner (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- New Jersey Diners (NJTV)

- Menu, Town and Country Diner, New Castle, Del. (New York Public Library)