Fries Rebellion

Essay

In 1798, while Philadelphia served as capital of the United States, a new federal tax and the Alien and Sedition Acts sparked resistance in rural Bucks, Montgomery, and Northampton Counties of Pennsylvania. The reputed ringleader John Fries (1750-1818) was twice convicted of treason but received a presidential pardon. Beyond local disruption, the rebellion played a national role in helping to fracture the Federalist Party and contributed to the first (and only) impeachment of a Supreme Court justice, Samuel Chase (1741–1811).

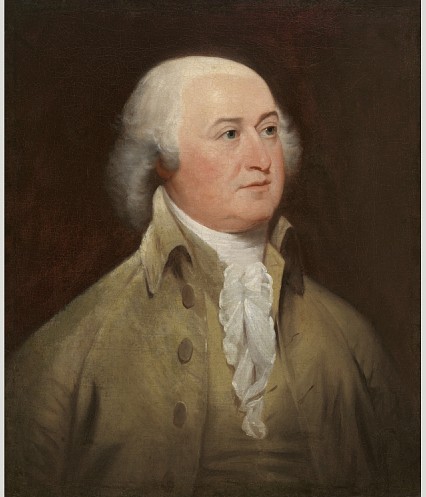

In response to growing tensions with France and confiscation of American ships, the Federalist administration of John Adams (1735-1826) expanded the American military to prepare for a potential war. To fund this expansion, on July 9, 1798, the Fifth Congress of the United States, meeting in Congress Hall, passed the House Tax Law, which imposed a direct tax on lands and dwelling houses. The Federalist government also passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, a set of four laws that curtailed the rights of immigrants and punished critics of the Federalist government.

Similar to the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-94, rural Pennsylvanians during the Fries Rebellion resisted federal legislation, resulting in mobilization of troops, imprisonment, and trial for treason in Philadelphia. In this case, the House Tax and Sedition laws angered many citizens in Northampton, Montgomery, and Bucks Counties, particularly the Germans, who viewed these acts as unconstitutional and designed to rob them of their property and liberty.

Resistance Commences

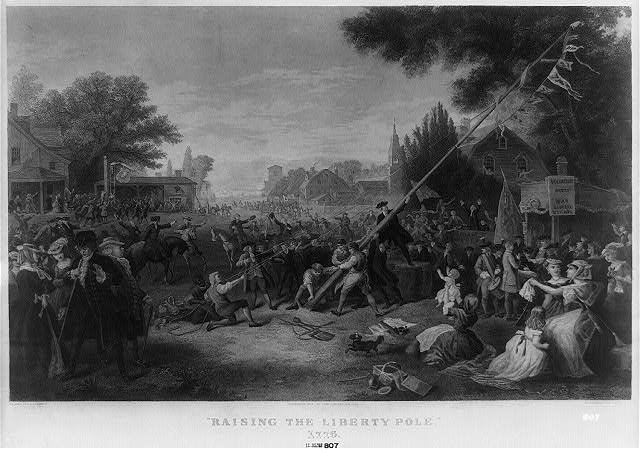

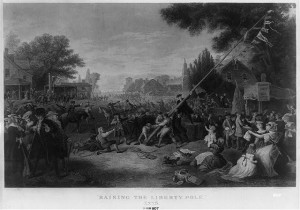

Resistance began in August 1798 less than fifty miles from Philadelphia, primarily in Northampton, Montgomery, and Bucks Counties, and increased through December with public denouncements of the acts and the erection of liberty poles. Through 1798, the rebels threatened violence against the tax assessors sent to these regions, but did little physical violence. In January 1799 the federal government issued arrest warrants for obstructing assessment of the House Tax. U.S. Marshal William Nichols left Philadelphia on February 25 to serve the warrants, which required resisters to appear for trial in Philadelphia. Nichols arrived in Northampton County on March 1, took twelve men into custody the next day, and served the remainder of his warrants over the next three days. He then retired on March 6 to his new headquarters and temporary jail for his prisoners, the Sun Inn in Bethlehem.

The next day nearly four hundred armed resisters entered Bethlehem in an attempt to free the prisoners. As the highest-ranking militia officer present, John Fries assumed command of the men. Once they reached the Sun Inn, Fries began negotiations with Nichols. As the negotiations dragged late into the day the uneasy crowd grew anxious. Nichols finally agreed to release the prisoners in order to calm the crowd and also to protect his deputies. In response to this event President Adams issued a proclamation from Philadelphia urging all insurgents to retire peacefully by March 18, 1799. The insurgents complied with Adams’ proclamation by March 18, but by that point Adams had already set the military into motion.

On March 22 the Philadelphia Aurora printed a notice from Secretary of War James McHenry (1753–1816) calling for Pennsylvania militia to assemble to put down the insurrection. In the same issue Aurora editor William Duane (1760–1835) severely criticized the Adams administration for its use of military force, a bold move when the Sedition Act was in place. The troops left Philadelphia on April 4 to quell the insurrection, meeting little resistance as they marched into Northampton County. They promptly arrested thirty-one insurgents, including John Fries, and returned to Philadelphia on April 20.

Fries and Two Others Face Trial

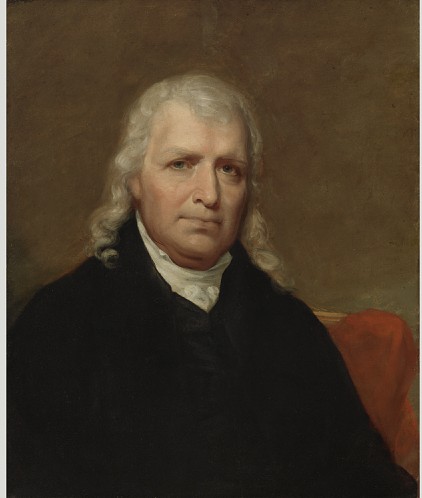

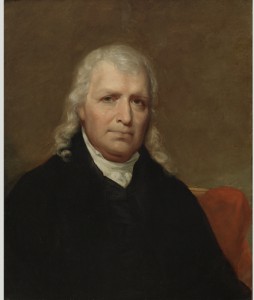

Fries and two others faced trial under the expanded definition of treason that Philadelphia lawyer William Rawle (1759–1836) put forth during the Whiskey Rebellion trials. Rawle, the lead prosecutor in the trial, had argued in 1795 that combining to defeat or resist a federal law was the equivalent of levying war against the United States and therefore was an act of treason. Fries’ trial began on April 30,1799, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Pennsylvania, which sat in City Hall (later known as Old City Hall, Fifth and Chestnut Streets). The jury convicted Fries of treason on May 9 and he was sentenced to death, but on May 17 a mistrial was declared when evidence surfaced that a juror had expressed a desire, before the trial began, to see Fries hang.

The second trial opened on April 16, 1800, with Judge Richard Peters (1744-1828) and Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase presiding. To expedite the trial Justice Chase issued a legal brief upholding the expanded definition of treason. The House of Representatives in 1804 cited Chase’s brief and actions during this trial among the articles of impeachment, of which the Senate acquitted him.

Fries was again found guilty of treason on April 25, 1800, and sentenced to hang on May 23. President Adams issued a presidential pardon for Fries and the two other men convicted of treason on May 21. This pardon was the last straw in a developing dispute between Adams and Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), who wrote to colleagues that the pardon was the “most inexplicable part of Mr. Adams’ conduct.” When published, this letter created a schism in the Federalist Party, helping Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) to defeat President Adams in the 1800 election. More generally, the harsh Federalist prosecution of the Fries insurgents and enforcement of the Alien and Sedition Acts encouraged Pennsylvania Germans and other voters to shift their allegiance to the Democratic-Republicans.

Patrick Grubbs is an advanced Ph.D. student at Lehigh University and is currently writing his dissertation entitled “Bringing Order to the State: How Order Triumphed in Pennsylvania.” He has also been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania History there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

National History Day Resources

- Alien and Sedition Acts, 1798 (National Archives)

- John Adams Proclamation 9 - Law and Order in the Counties of Northampton, Montgomery, and Bucks, in the State of Pennsylvania, March 12, 1799 (University of California - Santa Barbara)

- William Rawle Sr. Fries' Rebellion documents, 1799 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The two trials of John Fries, on an indictment for treason (Internet Archive)

- John Adams Proclamation - Granting Pardon to Certain Persons Engaged in Insurrection Against the United States in the Counties of Northampton, Montgomery, and Bucks, in the State of Pennsylvania, May 21, 1800 (University of California - Santa Barbara)

- Correspondence concerning Fries Rebellion (National Archives)