Medicine (Colonial Era)

Essay

In colonial Philadelphia, physicians and other medical practitioners contended with a difficult disease environment. The best medical efforts of the day were often inadequate or even harmful in the face of chronic illness and epidemic disease.

The health of the colonial population varied by race and region. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, as in the rest of the colonies, Native Americans were struck by epidemic diseases introduced from the Old World, including smallpox and measles. Africans and African Americans also suffered, facing overwork, malnutrition, and a new disease environment. European migrants brought European diseases with them, but they also encountered diseases imported from Africa, including yellow fever and a deadly form of malaria. Beyond these patterns, other variables also affected colonial health. Cities were less healthy than rural regions, as local and international trade networks facilitated the spread of disease and as crowding and improper disposal of wastes led to sickness. European immigrants often suffered from higher death rates than native-born colonists. Disease environments also changed over time. In general, the seventeenth century was healthier than the eighteenth. As the population grew and trade expanded, diseases spread more easily.

Philadelphia and the surrounding region stood at the intersection of these patterns. As a multiethnic city, Philadelphia had a population that included Native Americans, Blacks (both free and enslaved), and European immigrants from Britain, Germany, and elsewhere. In the colonial period, the city saw both chronic and epidemic threats to health. All colonial cities suffered from overcrowding and problems with waste disposal. At the same time, as a major port, Philadelphia was subject to epidemic diseases imported from Europe, the West Indies, and Africa. Local officials (in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey) tried to impose quarantines when infectious disease was known to exist, but such quarantines were of limited effectiveness. Even when human beings respected a quarantine, the mosquitoes that carried malaria or yellow fever would not. By the end of the seventeenth century, Philadelphia’s death rate exceeded its birth rate, and the city grew only because of continuing migration. Major killers in the region included chronic threats like dysentery and respiratory illnesses as well as epidemic diseases like smallpox and yellow fever.

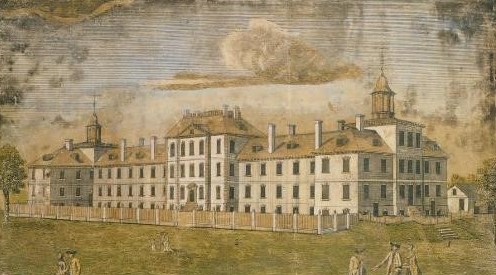

Pennsylvania Hospital

In confronting this disease environment, residents of the city turned to a wide variety of medical practitioners. Philadelphia was the site of one of the first hospitals in the British colonies, Pennsylvania Hospital, founded in 1751. Still, university-trained physicians were rare, and their services might be expensive. One historian estimated that in the 1770s, only about 200 physicians with medical degrees lived in all of the American colonies combined. These doctors had studied in Europe, as there were no medical schools in America until the first, the Medical Department of the College of Philadelphia, opened in 1765, drawing students from Pennsylvania and elsewhere. This school closed during the Revolution, but reopened in the 1790s. No medical school was founded in New Jersey in the colonial period, but New Jersey doctors formed the New Jersey Medical Society in 1766 in an attempt to professionalize the practice of medicine in the colony. Whether in Pennsylvania or New Jersey, most colonial doctors did not study medicine at school. Rather, they trained through an apprenticeship with a local physician, often studying and observing his medical practice for a three-year period.

But Pennsylvania and New Jersey residents also turned to other practitioners. Ministers commonly attempted to aid the sick with physical as well as spiritual help. In Elizabethtown, New Jersey, for example, the Reverend John Dickinson acted both as pastor and medical practitioner. Ordinary men and women might grow herbs, gather medicinal plants, or trade time-honored remedies with each other. Midwives aided women in childbirth, a realm of health care from which men were largely excluded. The belief that each land and climate produced both its own sicknesses and its own remedies led some colonists to seek advice from Native American healers, and American plants like guaiacum, sassafras, tobacco, and ipecacuanha (often called “Indian Physick”) had long been incorporated into colonial medicine. Colonists might also attempt to treat themselves or their families with the aid of medical handbooks. Major works printed or reprinted in Philadelphia included John Tennent’s Every Man His Own Doctor, first published in Virginia in 1734 and reprinted in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin in 1734, 1736, and (in German) 1749; William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine, first published in Edinburgh in 1769 and reprinted in Philadelphia in 1771, 1772, and 1774; and the theologian John Wesley’s Primitive Physick, first published in London in 1747 and reprinted in Philadelphia in 1764 and 1770 and in Trenton in 1788.

Popular medicine seldom had a strong theoretical basis. Plants or other remedies were popular because they worked (or seemed to work), often by causing powerful physical reactions. Those who read Every Man His Own Doctor, for example, would have found many remedies advising that the sick person be dosed with “Indian Physick” (ipecac) to cause vomiting or suggesting that a medicine made from mallow (an imported herb) and peach-blossom syrup would cause purging. Buchan preferred milder remedies, though noting that bleeding and purging could sometimes be useful. Wesley, on the other hand, was far more suspicious of doctors. In Primitive Physick, he maintained that temperate habits and moderate exercise could ward off many diseases, and that drinking water could treat many illnesses effectively. Doctors, he thought, had made medicine unnecessarily complicated in order to gain money and honor for themselves.

Theories of Medical Procedure

University-trained physicians deplored the lack of system in such popular remedies. The Philadelphia physician John Morgan (1735-89) was among the first professors in Philadelphia’s medical school. In his Apology for Attempting to Introduce the Regular Practice of Physic (published in Philadelphia in 1765) he proudly declared that he had studied with “the most celebrated masters in every branch of medicine” in Europe. The human body, he wrote, was so complex that long years of education were necessary to understand its workings. Formal medical training was vital, for an untrained or half-trained physician was as likely to inadvertently poison a patient as heal him or her.

Morgan and other university-trained physicians were profoundly influenced by the ideas of leading European physicians, including the Dutch doctor Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) and the British physician William Cullen (1710-90). Boerhaave had theorized that the human body was made up of “solids” and “fluids,” which must be kept in balance. Disease resulted from imbalances in the solids and fluids, which could often be remedied by bleeding or purging the patient to restore balance. Cullen’s theory of medicine was somewhat different, as he believed that diseases might be caused by contagion from another person or by breathing infected air (a miasma). Their remedies, however, were much the same. Eighteenth-century doctors in Philadelphia, as in Europe, generally believed that the best cures had dramatic effects on the body. Medicines that caused vomiting and purging (including ipecac and jalap) were popular, as was mercury (to cause salivation). Such treatments were intended to restore balance to the body by drawing off corrupt or excessive matter. Doctors also relied on bleeding, which might have the additional benefit of lowering a fever or even causing a suffering patient to lose consciousness. For those who trusted these doctors, the dramatic effect of their medicines testified to their strength. Skeptics argued that such powerful drugs could only weaken a sick person. One satirical poem summed up the remedies of the day: “Piss, Spew, and Spit, / Perspiration and Sweat; / Purge, Bleed, and Blister, / Issues and Clyster.”

Philadelphia was at the center of a major medical controversy during the American Revolution, when a smallpox epidemic ravaged the colonies between 1775 and 1782. A process for inoculation for smallpox had been known for much of the 1700s. It involved taking pus from the sores of a smallpox victim and introducing the infected matter into an incision in a healthy person. That person would then contract smallpox, but usually in a milder form. Inoculation was controversial in the 1700s, not least because an inoculated person, while sick, was fully contagious. Since inoculation was quite expensive, poorer citizens resented the idea that the wealthy, by inoculating themselves, put the larger community at risk. Nonetheless, inoculation was quite common (and unregulated) in colonial Philadelphia. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Patrick Henry (1736-99), and Martha Washington (1731-1802) were all inoculated there. During the American Revolution, George Washington (1732-99) ordered soldiers inoculated. In Pennsylvania, military inoculations took place in Philadelphia, Newtown, and Bethlehem.

Colonial Philadelphia’s status as a growing city and a major port led to a dangerous disease environment. Its institutions (including the first American medical school and Pennsylvania Hospital) were among the first of their kind in the colonies, but in the end, most of the medical treatments of the day could do little to slow or stop the spread of sickness.

Martha K. Robinson is Associate Professor of History at Clarion University of Pennsylvania. Her publications include “New Worlds, New Medicines: Indian Remedies and English Medicine in Early America,” Early American Studies 3 (Spring 2005): 94-110. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- "Pick Your Poison: Intoxicating Pleasures & Medical Perscriptions." Digital Exhibit (U.S. National Library of Medicine)

- "And There's The Humor of It: Shakespeare and the Four Humors." Digital Exhibit (U.S. National Library of Medicine)

- "Every Necessary Care and Attention: George Washington and Medicine." Digital Exhibit (U.S. National Library of Medicine)

- "Emotions and Disease." Digital Exhibit (U.S. National Library of Medicine)

- "Under the Influence of the Heavens: Astrology in Medicine in the 15th and 16th Centuries." Digital Exhibit (Historical Medical Library of of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia)

- Past Exhibitions of the Mütter Museum (Mütter Museum)