Philadelphia Gas Works

Essay

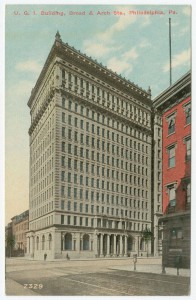

The Philadelphia Gas Works (PGW), founded in 1836, was in 2015 the largest municipal-owned utility in the United States. While supplying residents with fuel for heating and cooking, PGW also became a flashpoint of controversy over whether such a utility should be owned by the city or operated by a private corporation. Although a number of cities in the United States own public utilities to provide electricity, Philadelphia is one of the few that sells gas to its citizens. A plan to sell PGW in 2014 stalled in City Council.

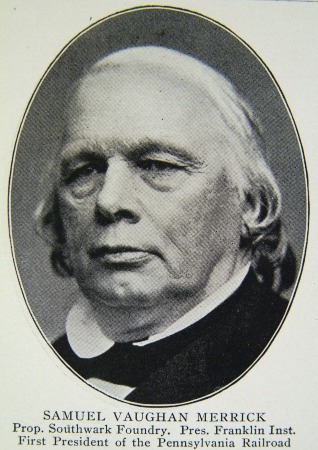

PGW originated in the 1830s from Philadelphia’s desire to catch up with other cities in providing gas lighting for streets, businesses, and homes. Although Philadelphia was the fourth-largest city in the country in 1837, it lacked a municipal gas works. In 1835, voters elected Samuel Vaughan Merrick (1801-70), an engineer and entrepreneur, to the Common Council to push Philadelphia towards building a gas works. Deeply involved in the city’s development, Merrick was one of the founders of the Franklin Institute and the first president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. After traveling to Europe to investigate municipal gas works, Merrick persuaded Council to charter a private company to build the works, but the Council retained the right to acquire it. Thus the experiment was to be started with private funds, but if it worked out, the municipal government could claim the gas works.

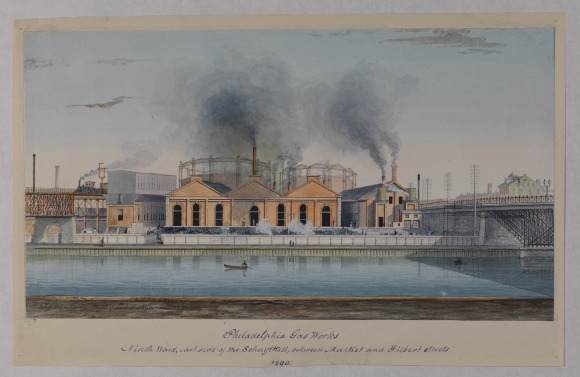

Merrick designed the plant himself for a location on the Schuylkill River near Market Street. Opened on February 8, 1836, the facility used Pennsylvania coal to produce gas. PGW delivered this gas within Philadelphia’s original boundaries, the area between Vine Street and South Street and between the two rivers. In the first few years of operation, PGW installed cast iron pipes about two feet below the city’s surface to bring gas to many of the outdoor lamps lining Philadelphia streets, giving a distinct look that came to define nineteenth-century cities. Hotels, stores, and other public places also quickly installed gas, which rapidly replaced oil for illumination. Private use of gas lighting grew more slowly because the cost of lighting homes was beyond the reach of the city’s working class.

City Assumes Ownership

Convinced of the gas works’ growing profitability, in March 1841 the Philadelphia government took over ownership of PGW. After Philadelphia’s consolidation with the county in 1854, PGW acquired the local companies in the annexed territory, extending its reach fully into the 129.7 square miles that made up the new city. By 1890, 1,500 public lights lit Philadelphia’s streets and two million lights lit private homes.

After 1860 PGW’s problems came not from the need to add customers, but from political changes in Philadelphia. Between 1860 and 1951, Republican political bosses controlled city government and used PGW’s board of trustees as a source of patronage. James McManes (1822-99), as head of the city’s gas commission, took kickbacks from contractors and employed a large number of the gas works’ 1,000 employees as election workers, allowing him to gain control over the Republican Party. Under his rule, PGW operated inefficiently, fell into debt, and as a consequence charged higher prices for gas to private customers than any other city.

By the late 1880s PGW’s operations had almost completely broken down. The Gas Commission was an independent agency, but its members, who were appointed by Council, were either Republican ward leaders or subservient to ward leaders. The commission refused to adopt numerous technical improvements in the production and distribution of gas. Costs to consumers were high for what proved to be an inferior product. Safety was not a priority, and accidents frequently happened. The status of the works became a national disgrace as journalists wrote about the “gas house gang” and the greedy politicians who ran the city through their control of PGW. The situation was not entirely unique to Philadelphia, as other cities such as St. Louis had political bosses who ran local public utilities for personal gain. However, when the journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote about bad government in American cities, he found Philadelphia among the most corrupt. During the Progressive Era, reformers in a number of cities removed ward leaders from control over public utilities.

Ownership Compromise

Trying to remedy the situation, in 1897 a broad movement among consumers and good-government groups in Philadelphia proposed selling the gas works to a private company. But political opposition to a sale resulted in a compromise. Philadelphia leased the system to the United Gas Improvement Company (UGI) for 30 years, renewing it every ten years thereafter until 1972. Under the arrangement, UGI sold the gas, maintained the production plants, and paid the city an annual rental fee, which averaged about $1.5 million through the first quarter of the twentieth century, rising thereafter with each new contract. UGI remained a Philadelphia corporation, whose leaders included a number of businessmen also involved in building the city’s transportation system. The company owned a number of local gas companies along the East Coast and during the 1920s was one of the largest utility holding companies in the United States.

Although Republican bosses who controlled Philadelphia politics during the early twentieth century made several attempts to gain control over the gas works, PGW remained largely immune to corruption during its 70 years of operation by UGI. Gas usage expanded greatly. Even as more homes converted to electricity for lighting, they adopted gas for cooking, refrigeration, and heating water. Nevertheless, controversy periodically erupted over whether the city should take back control of this vital asset. The leaders of the Republican machine such as Boies Penrose (1860-1921) and William Vare (1867-1934) wanted more access to the gas works patronage and its valuable construction contracts. The most politically charged attempt to take over the gas works occurred in 1938 when Mayor S. Davis Wilson (1881-1939) tried to seize the company’s facilities despite a vote by the Council granting UGI a new lease. Before the dispute ended with an injunction from the state Supreme Court, Wilson sent the police to take over the gas works buildings. Hundreds of people, including PGW employees who were defending the plants against the police, were involved in the near-riot. After the court’s decision, UGI’s contract remained in place. Ironically, with the city unable to pay its operating expenses in 1938 because of the Depression, the Council used the gas works as collateral to borrow $40 million from a federal agency.

After World War II, PGW grew rapidly, with revenue of over $100 million by 1970. Change occurred as most residents and businesses adopted gas heating to comply with new pollution regulations, which largely eliminated coal for winter heating. To meet demand, PGW expanded its services by maintaining retail stores, operating a fleet of repair trucks, automating its billing system, and switching production in its own plants from coal to natural gas. Financially, PGW’s relationship with the city was complicated by Philadelphia’s dire budget needs. In 1965 the Council again used the gas works as collateral for a loan, and a few years later it secured an advance on payments from UGI.

Political Pressure to End Lease

Whenever the contract between the city and UGI came up for renewal, politicians used the occasion to urge the end of the lease. After 1951, the pressure came from Democrats, the new majority party in the city. In the 1960s, Controller Alexander Hemphill (1922-86), with considerable support within Council and among leading Democrats, led the opposition to granting a new contract.

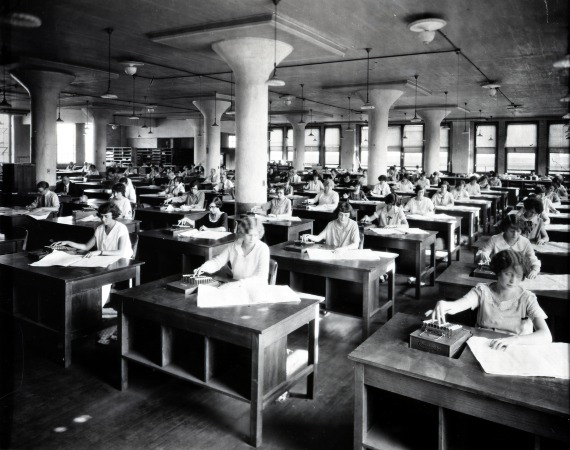

In 1972, Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91) decided to end the contract with UGI and replace it by creating the Philadelphia Facilities Management Corporation to run PGW. The new municipally-run company served 556,000 customers and delivered the gas through 2,932 miles of gas mains. In its first days, the new company’s top managers were people who had worked for UGI before the lease expired, and the board included a number of distinguished Philadelphians.

From the start of PGW’s new status, it faced serious problems because of inflation, rising natural gas prices, and high interest rates on bonds for capital construction. Philadelphia also had serious fiscal difficulties and relied on the $15 million fee paid by PGW to meet its obligations. On several occasions, some of Philadelphia’s leaders suggested selling the facility. One major point of contention was gas rates, which many consumer groups believed were too high. Costs for the average homeowner rose from about $180 a year to $894 during the first 20 years of city control. Part of the rise in rates occurred because of inflation during the 1970s and part because of the disruption of energy supplies during the same period. But these national causes did not help ensure a smooth transition for the gas works to public operation.

After 1972, controversies over PGW became a regular part of Philadelphia’s political landscape. An additional concern about rates was the inability of persons living near the poverty level to secure heat during the winter. When City Council prohibited the termination of gas for such individuals, the loss of income was great enough to push the gas works close to bankruptcy and prevented its annual payment to the city. On several occasions, the city had to bail out PGW to help it pay its bonded indebtedness. Even when the $15 million annual fee materialized for the city’s benefit, PGW remained a source of controversy, such as the board’s decision to build a gas generating plant in the 1970s and 1980s that never was used.

The end of the UGI contract in 1972 further politicized PGW’s operations. One of Rizzo’s initial actions was to shift the law firm representing the gas works to a political ally. Additionally, the Gas Commission, composed of the controller, representatives of the mayor, and the Council, assumed control over PGW. Patronage began to play a part in the makeup of the workforce once again, and allies of mayors gained the business of sales of bonds and the contracts for legal work. In 1986 this mixing of politics with gas led the two most important officials from PGW to resign in a dispute with Mayor Wilson Goode (b. 1938). About the same time, PGW hired ex-mayor Frank Rizzo as its security director when he was attempting to regain his old office, a situation that prompted considerable controversy.

Over the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century, further political problems surfaced. Several major scandals led to the resignation of top leaders, and the question once again emerged: Could the city effectively run a public utility, or should it be sold to a private corporation? Mayor Edward Rendell (b. 1944) explored the issue in the 1990s, and Mayor Michael Nutter (b. 1957) in 2014 opened bidding to secure a sale. UIL Holding Company of Connecticut won the rights to buy PGW for $1.86 billion. Mayor Nutter proposed that the money be used to fill a very large hole in the city pension fund. But the Council rejected the offer as members expressed fears about the loss of control over what had been a source of patronage and funds for the city. Workers at PGW feared what a change in ownership would mean for their jobs. More generously, some expressed concern that poor city residents would lose their protection from having their gas turned off because of nonpayment of bills during the winter.

For almost two centuries, PGW remained a major institution in Philadelphia. But political disputes throughout its history often overshadowed PGW’s usefulness as a city-owned municipal facility. During the same period, cities such as New York and St. Louis sold off their gas works, which often were combined with electric companies as a means of providing easy billing for customers and clear regulatory control over rates. Philadelphia during this era faced a constant conundrum: Would its residents be better served by a gas works run by a city run utility or by a private company?

Herbert B. Ershkowitz is Professor Emeritus at Temple University and the author of three books and numerous articles on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American history. He wrote a 150-year history of PGW that is available in the PGW archives.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- PGW paying $500,000 to settle civil action after 2011 Tacony explosion (WHYY, July 17, 2013)

- Philly Council President accepts petitions against PGW sale (WHYY, May 27, 2014)

- Deal to sell Philadelphia Gas Works still alive, for now (WHYY, July 16, 2014)

- Pa. officials want PGW sale to move forward (WHYY, October 29, 2014)

- Philly council introduces resolution instead of PGW sale (WHYY, October 30, 2014)

- PUC pushes Philadelphia to ramp up replacement of leaky gas pipes (WHYY, January 13, 2015)

Links

- Philadelphia Information Locator Service: Philadelphia Gas Works (Philly.gov)

- Lincoln Steffens, Excerpts from "Philadelphia: Corrupt and Contented," July 1903. (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Philadelphia Gas Works (PDF, Mueller Record, 1976)

- It's a Gas! Mayor Dilworth Extinguishes Philadelphia’s Last Municipal Gas Streetlight