Salt Making

Essay

Colonial Americans depended on Great Britain for many necessities. Primary among them was salt, the essential ingredient in curing meats and preserving foods through the winter. At the start of the American Revolution, the British Navy blockaded American ports and largely shut off the supply of imported salt. In Philadelphia, salt prices shot upward. Starting in July 1775, the Continental Congress passed resolutions designed to hold down salt prices and spur domestic salt-making. By early 1776, several states passed measures to fund salt works on their coasts.

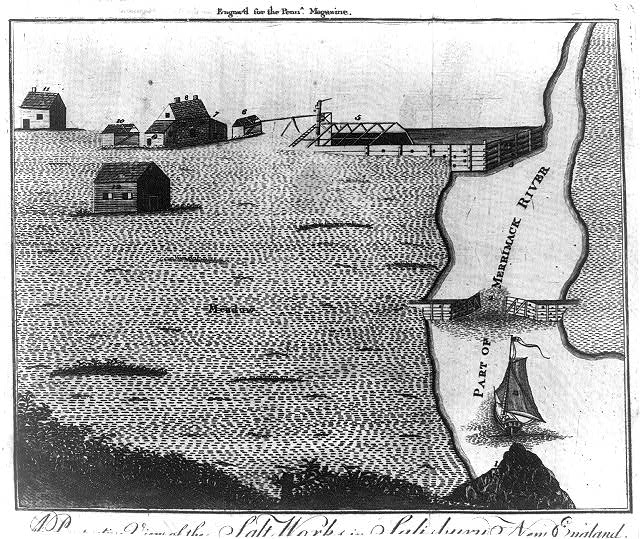

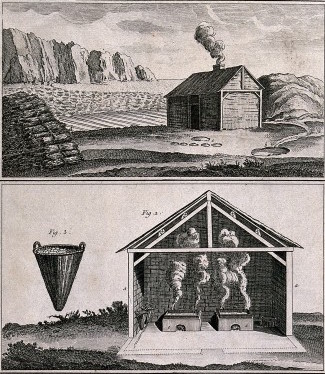

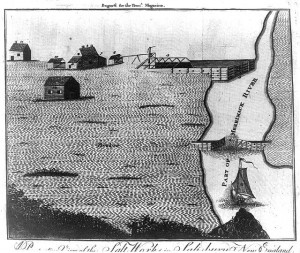

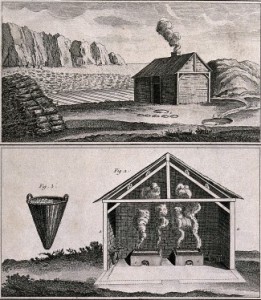

Lacking their own coast, Pennsylvanians looked to the nearby New Jersey shore for salt-making opportunities. In May 1776, Thomas Savadge (d. 1779), a Philadelphia merchant who had failed at iron mongering a decade earlier, proposed to the Pennsylvania Council of Safety a plan for a large-scale salt works on the Jersey shore. Even before the council agreed to underwrite the plan, Savadge went to New Jersey and purchased 500 acres of salt marsh near Toms River. Within a few weeks, he hired more than twenty laborers and started constructing the Pennsylvania Salt Works. The men constructed gated canals for trapping sea water, brought in pumps for moving the water into drying vats, and built “houses” lined with large kettles for boiling salt brine into usable salt. In October, Savadge reported back to Philadelphia on his considerable progress, and hinted that the salt works were nearly ready to begin large-scale salt production.

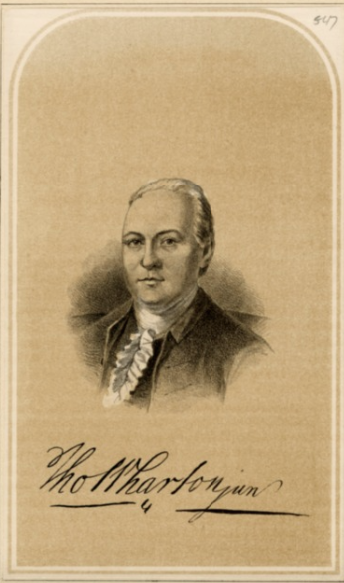

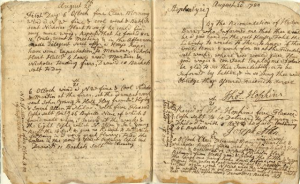

However, Savadge was overoptimistic. In December 1776, the Continental Army withdrew from New Jersey and emboldened Loyalists assumed control of the state. Fearing the works would be attacked, Savadge rode out to meet a John Morris, the Loyalist colonel in charge of the area. Savadge convinced Morris not to burn down the salt works, but Savadge had to leave the works. When the Continental Army retook central New Jersey in January 1777, Savadge returned, but the workers had abandoned the site. In a series of letters to Philadelphia in early 1777, Savadge complained about lacking laborers, lacking funds, and being vulnerable to enemy attack. Throughout 1777 he asked Pennsylvania for greater support and its government responded with additional funds and a 25-man guard. It also pressured the New Jersey government to grant militia exemptions for salt-works laborers. Despite this support, the Pennsylvania Salt Works were still not producing salt by the end of 1777. Communications between Savadge and his benefactors became strained. Thomas Wharton (1735-78) of the Council of Safety warned: “We have been most egregiously disappointed and are almost induced to give up the matter.” Savadge responded that he expected the salt works to produce 30,000 bushels of salt in the next year.

In April 1778, a Loyalist raiding party razed the competing salt works at Manasquan and Shark River, prompting Savadge to again request a new guard and additional money. This time, the Pennsylvania Council of Safety was unsympathetic. In a terse letter on behalf of the council Thomas Wharton refused Savadge’s request and called the salt works “long in the hand” and “altogether fruitless.” The council appointed James Davison to inspect the salt works. By the end of 1778, Savadge was removed from managing the salt works and back in Philadelphia. He died while waiting on the Pennsylvania government to settle his accounts. There is no evidence to suggest that the Pennsylvania Salt Works ever produced any salt. The Pennsylvania Salt Works were sold at public auction in November 1779 to New Jersey investors who were able to produce modest amounts of salt from the failed works. But once the salt works at Toms River were razed by Loyalist raiders in March 1782, they were never rebuilt.

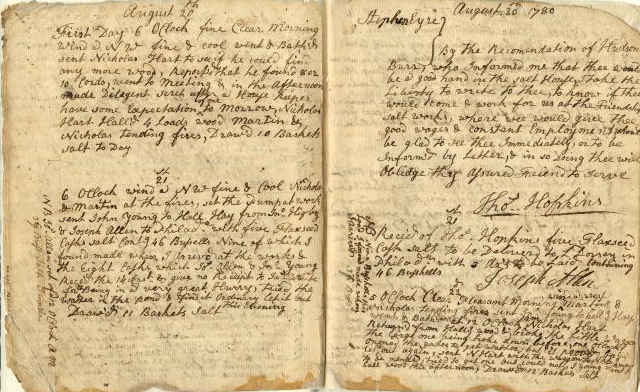

The Pennsylvania Salt Works and the comparably-large Union Salt Works, at Brielle, were both failures. Up and down the Jersey shore, nine of eighteen known salt works were destroyed during the war. But several of the smaller operations, including the Friendship Works owned by Thomas Hopkins of Philadelphia, were successful. However, the salt-making boom of the Revolutionary War years was temporary. By war’s end, imported salt from Europe returned to the American market and pushed the domestic salt-makers into retirement. The Jersey shore was never again a salt-making hotbed. In the late 1700s, Americans discovered inland salt deposits, including some minable sources in northwestern Pennsylvania near the New York border. But competing salt licks near the Cheat River in present-day West Virginia and the Ohio River in eastern Kentucky were closer to major navigable rivers and became more significant suppliers. Salt-making never took hold as a major industry in Pennsylvania.

Michael Adelberg has been researching the American Revolution in New Jersey for twenty-five years. He is the author of “ ‘Long in the Hand and Altogether Fruitless’: The Pennsylvania Salt Works and Salt-Making on the New Jersey Shore during the American Revolution” in Pennsylvania History, and articles published in The Journal of Military History and The Journal of the Early Republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- "The Capture of the Block House at Tom's River, New Jersey, March 24, 1782" read at the memorial service at Toms River May 30, 1883 by William S. Stryker (Google Books)

- Thomas Hopkins Journal, 1780 finding aid (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Journal of Thomas Hopkins of the Friendship Salt Company, New Jersey, 1780 (Google Books)