Slovaks and Slovakia

Essay

Slovak migration to the Philadelphia region was no less a part of the Slovak experience in the United States than the larger Slovak migrations to Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, or Chicago. Although much smaller and often overlooked in larger migration accounts, Slovak-speaking workers contributed to Philadelphia’s reputation as a “Workshop of the World” through their contribution to many artisanal trades and commerce as well as their employment as laborers in heavy industry and domestic service.

Little is known about Slovak speakers in eastern Pennsylvania and the surrounding region during the colonial period as early American Republic immigrants were not required to identify their native language with authorities, only their country of origin. Slovakia did not exist, and migrants listed Hungary, Austria, or Germany as their country of origin or last residency when required. Despite the difficulty in identifying them, Slovak speakers were present in North America at least since the seventeenth century, and their numbers gradually increased throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The earliest Slovak speaker in colonial Pennsylvania on record, Isaac Ferdinand Saroschi (also known as Isaacus Sharoshi or Izák Šároši), left a teaching position as dean of students in Bavaria under Tobias Schumberg (1627-1713) and travelled to Germantown in April 1695 to devote himself to teaching and religious ministry as a Lutheran pastor within the new colony. Nearly fifty years later, Anton Schmidt (1725-93) of Pressburg left Hungary with his parents and settled in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 1746 as a member of the Moravian Church or Unitas Fratrum. A tinsmith by trade, Anton and his wife, (Anna) Catharina (1727-62), were active missionaries among the Iroquois in Shamokin (later Sunbury), Pennsylvania, where his smithing was in great demand.

As industrialization developed and the need for labor grew during the nineteenth century, Philadelphia served as an entry port and transit point for many Slovaks heading for the anthracite and bituminous coal regions farther inland and westward; the iron and steel mill cities of Bethlehem and Pittsburgh; and textile mills in Clifton Heights and nearby Camden as well as farther north in Bayonne and Passaic in New Jersey. Not all Slovaks saw Philadelphia and the nearby area as a merely a transit point, however.

Wirework in Demand

As early as the 1840s, wireworkers set up businesses in Philadelphia despite the anti-immigrant tension within the city. Decorative and functional wireworking was much in demand, and members of the Komada family of Veľké Rovné in the Trenčin region of Upper Hungary were the first to offer their services in the city. The Komadas maintained businesses in many cities in Europe and America, and a branch of this family settled in the Quaker City permanently by 1876. In addition to the Komada family’s wireworks, the Berko brothers, also of Veľké Rovné, were the first to build a wireworks and ironworks factory, located at Randolph and Wood Streets. Adam Nekoranik (1887-1963) of Vysoká was also an early wireworker from this time. Other families followed, setting up businesses on streets around the future site of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge: the Raysik wireworking firm, c. 1885, Marčis, Babušik, and A. Halgas, to name but a few.

Immigration was not exclusively limited to wireworkers, however, and artisans who specialized in leatherworking, cigar-making, and textile production settled in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia and eventually throughout the city and nearby New Jersey. Together with the wireworkers, these skilled entrepreneurs and artisans were known as Hričovci after Dolny Hričov, a main settlement in the Trenčin region where many of these immigrants originated.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, Slovaks came under increasing financial, cultural, and political pressure in their native lands. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 gave complete autonomy to the Hungarian ruling class to govern their kingdom. While provisions stipulated for non-Hungarians to remain within the country, a change in political leadership in the early 1870s prompted Magyarization policies to close Slovak schools and social organizations and discourage the Slovak language. High birthrates, poor agricultural yields, malnutrition, and a cholera epidemic in 1873 exacerbated living conditions. With limited opportunities in a country dominated by agriculture cultivated on large aristocratic estates, individuals and later whole communities sought their livelihood elsewhere, both throughout Europe and the Americas. Many planned to stay long enough to generate capital to support their families back home and eventually purchase land or start businesses in Hungary. During this migration period, which lasted until World War I, approximately one-third of Slovaks eventually returned to Hungary/Slovakia having achieved some means of financial stability.

It was during the 1870s that another Slovak group migrated to Philadelphia from the regions of Zemplín, Spiš, and Šariš in eastern Hungary. Originally from the village of Hutka and its surroundings, they were known as Hutoráks or more generally as Zemplínčania to the earlier Hričovci migrants. Hutoráks worked and lived near the industries that employed them: in Southwark, as day laborers, stevedores, and deliverymen; in Nicetown as laborers in factories like Midvale Steel, Budd Car, and Link Belt as well as the Pennsylvania Railroad; in Point Breeze, as workers in the Philadelphia Gas Works and the Atlantic Refining Company. Farther afield, they worked in oil refineries in Paulsboro, New Jersey. Hutoráks spoke an eastern dialect of Slovak, which was not always mutually comprehensible with the western or central dialect of the Hričovci.

Slovak Women and Household Income

Wherever they settled, Slovak women from both regions worked both inside and outside the home as laborers in textile mills, as domestics, housekeepers, and launderers, and for many married women as landladies who took on boarders or lodgers in their homes. Often when work was slow or unavailable for Slovak husbands, the incomes of Slovak wives kept families from total impoverishment. Some ran their family businesses, such as Anna Raysik (1885-1968), who operated the main branch of the family wireworking firm in Philadelphia until 1917, or Mary Lehota (1876-1952), a midwife who offered her services from her own professional practice in the city.

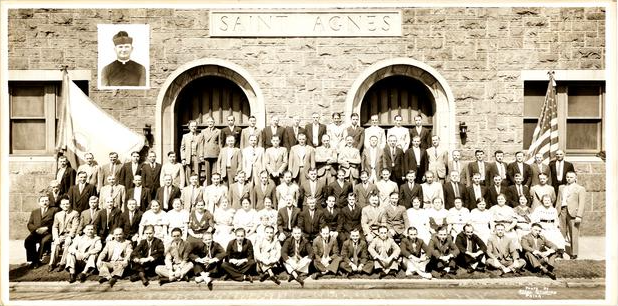

Slovaks lived in multiethnic neighborhoods in Philadelphia and no one place became distinctively Slovak, not even Point Breeze, which had a large Hutorák community. Because they did not plan to stay in the United States for very long, they worshipped at churches throughout the city depending on their confessional beliefs. As time passed, they formed their own churches, starting with Holy Ghost Greek Catholic Church (1891) at Nineteenth Street and Passyunk Avenue, Holy Trinity Slovak Evangelical Lutheran (1900) at 609-611 N. Franklin Street then later at 721 N. Fifth Street, St. John Nepomucene Roman Catholic Church (1902) at Ninth and Wharton Streets, later the breakaway St. Agnes Roman Catholic Church (1910) at Fourth and Brown Streets, and Assumption of the Holy Virgin Russian Orthodox Church (1913), a breakaway from Holy Ghost located at Twenty-Eighth and Snyder Streets. Philadelphia’s trolley system made it possible for a Slovak family in Nicetown to worship at St. John Nepomucene eight miles away or Clifton Heights Slovaks to travel to St. Agnes for Sunday service. For the small number of Slovak Protestants, Holy Trinity Slovak Evangelical Lutheran Church served the Philadelphia-Camden-Pottstown regions some forty miles apart.

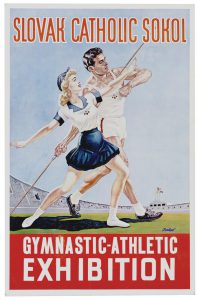

Itinerancy permeated Slovak lives and continued as second and third generations settled outside the city core yet kept ties to their churches. They maintained community less through proximity to other Slovak residences and more through familial and social memberships in churches, fraternal-benefit societies, National and Catholic sokol and soedinenie or gymnastic unions, private clubs, bars, and workplace ties that spanned political, religious, and geographic boundaries. Cultural and religious events such as live theater or divaldo and traveling Christmastime shepherd plays or jasličkari (also known as gubis) among the eastern Slovaks were some ways that a dispersed community found cohesion. Ultimately these ties helped Hričovci and Hutoráks realize their shared Slovak identity in the early twentieth century. From an economic perspective, many networks provided information on employment opportunities that allowed Slovaks mobility within Philadelphia and throughout the country. Likewise, those networks brought Slovaks into Philadelphia when times were difficult in the coal mines or other extractive communities.

By 1900, some Slovaks had moved beyond the main areas of first settlement to live in Bridesburg, Burlhome, Fairhill, Kensington, Manayunk, and Richmond in North Philadelphia and farther afield into Bucks County; Grays Ferry in South Philadelphia; and westward into Delaware County. In 1910, they numbered about two thousand within the city of Philadelphia.

Catholic Groups Split

The difference in spoken dialect created tension between the two main groups of Slovaks and led to a split between Hričovci Roman Catholics, who left Saint John Nepomucene Church to found Saint Agnes Church apart from the Hutoráks, who remained parishioners at the first Catholic Church. Written forms were less contentious, especially as written Slovak became important to the cause of nationalism and separation from Hungary. For those eastern Slovaks who could read and write their native language, the eastern written form created from Hungarian was quickly replaced in the few publications that used it, and central Slovak was adopted as the literary language in secular newspapers, bulletins, religious hymnals, and sermons. Due to the significance of Philadelphian Slovak community, The Society of Slovak Roman Catholic Priests met in Philadelphia in 1903 and concluded that all preaching was to be done in the central dialect to further the cause of Slovak nationalism and eventual independence from Hungary.

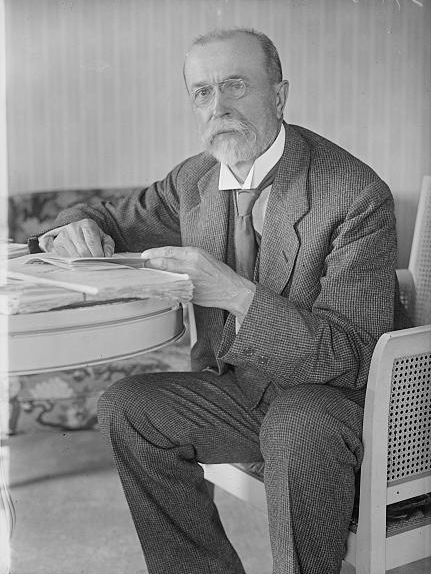

When war broke out in Europe, Hričovci and Hutorák alike monetarily backed the Cleveland Agreement of 1915, which obligated expatriate Slovak leaders to support the Bohemian National Alliance’s independence movement for Czech and Slovak lands from Austria-Hungary. Fundraising activities helped Slovak communities perceive themselves as independent of their countries of origin, and animosity toward anything German or Austro-Hungarian in the United States during the war years helped many Slovaks disassociate from these nations. Putting aside mutual indifference, Slovaks and Czechs of the region rallied behind the nationalist cause. Members of both Slovak Roman Catholic churches plus delegates of the Svatopluk Slovak Club sent a contingent to Independence Hall in 1918, where Czech delegate Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937) joined delegates from twelve other Central and East European nations to deliver a Declaration of Common Aims that asserted independence from Austro-Hungary and Prussia. By war’s end, Hričovci and Hutoráks buried their old regional differences to identify as Slovaks and to support the new Republic of Czechoslovakia.

When the census was taken in 1920, around eight thousand Slovaks lived throughout Philadelphia with an additional one thousand in nearby cities such as Clifton Heights and Camden, New Jersey. To help ameliorate the problem of meeting space for the many Slovak groups throughout the Philadelphia region, Slovak Hall was built in 1921 after nine years of planning and deliberation. Located at Fifth Street and Fairmount Avenue, the hall replaced a previous meetings space created by the Svatopluk Slovak Club and included a bar, dance floor, meeting rooms, and a gymnasium. Many groups contributed their labor and their finances to its construction, chief among them being the wireworkers.

Slovak Hour Radio

By 1930 between eight thousand and ten thousand Slovaks were living in Philadelphia, a city then of over 1.8 million residents. Although there were no local Slovak newspapers of note, in 1932 the Slovak Federation of Philadelphia sponsored a radio program known as the “Slovak Hour.” By 1934, the program aired over WDAS-AM along with other ethnic programs in Polish and Yiddish. The program’s announcer Karol or “Charlie” Valach (1892-1952) with his niece, Emily Valach (b. 1922), invited musicians and vocal groups to provide live music on air. As musicians union rules changed, live performances gave way to recordings. Upon Valach’s death, Michael Sas (1907-75), recording secretary for the Slovak Federation, became the program’s announcer and served until his death.

Prior to the 1930s, religious and fraternal groups were the only support that many Slovaks had outside of their family when difficulties arose. As New Deal legislation became reality, however, the need for benefit and fraternal societies diminished. The National Housing Act of 1934 coupled with the Wagner and Social Security Acts of 1935 addressed many of the critical issues that these groups and other political and union groups raised in previous decades. A number of Slovak laborers drawn to radical, anarchist, and communist causes in the first part of the twentieth century saw their influence diminish as Slovak labor sought to conform and Americanize, particularly as World War II ended and the GI Bill of 1944 offered new avenues into the middle class. Although uncommon, federal agents questioned members in suspect groups along with their reading habits throughout the Greater Philadelphia area. For those who continued to agitate, the external pressure placed on them by the McCarthyite press, fellow Americans, the U.S. attorney general, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation made their message less viable during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Also during the 1950s and 1960s, the proliferation of televisions and television programming provided a new American cultural norm that Slovaks and other white ethnics adopted as they moved physically and professionally into the middle class suburbs. Professional football legend Chuck Bednarik (1925-2015), who played for the Philadelphia Eagles from 1949 to 1962, and Major League Baseball player Johnny Kucab (1919-77), who played for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1950 to 1952, made Slovak-Americans household names and were as much a part of professional American sports and popular culture as they were of the Slovak communities of their upbringing. The appeal of the Philadelphian social and religious events as well as live performances at Slovak Hall and other clubs seemed quaint by comparison, and many distinctly ethnic venues closed during this time, including Slovak Hall in 1967. The tension that once caused a split among Roman Catholics evaporated in the face of declining memberships and church consolidations, leaving St. John and St. Agnes to merge in 1980 and Trinity Evangelical Lutheran to close in 1988. The Slovak Radio Program gradually ceased operations at this time as WTEL-AM increased its sports coverage, and Slovak businesses downtown that operated at prime real estate sites saw opportunities to sell their properties as the trend toward adaptive reuse through Historic Preservation Tax Credits was introduced in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Wirework factories were converted into luxury condominiums in desirable upscale communities. Even the Komada wireworks succumbed, closing its business in 2009.

Despite assimilation and Americanization of the twentieth century, new Slovak organizations formed, even as a number continued to operate. In 2008, the Greater Philadelphia Czech and Slovak Meetup Group began an online social networking site to share cultural activities happening in the region such as the Mikulasska Nadilka, or St. Nicholas Party, and in 2010, Comenium, a Czech and Slovak School for Greater Philadelphia, began offering language classes and performance and recital venues for children of both communities. Whether these groups represented a renewed interest among longstanding Slovak descendants in their cultural heritage or a desire for more recent Czech and Slovak immigrants to form a sense of community, Slovaks remained a visible part of Philadelphia and the greater region into the early twenty-first century.

J. A. Reuscher is an Associate Librarian with the Pennsylvania State University Libraries and holds degrees in history and library science. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Anton Schmidt: The Lost Village of Christian's Spring (Lehigh University)

- Friends of Slovakia

- Pittsburgh Agreement Historical Marker (Explore PA History)

- The Shamokin Diaries 1745-1755: The Moravian Mission to the Iroquois (Bucknell University)

- Slovak Catholic Sokol

- St. Agnes-St.John's Nepomucene Roman Catholic Church (PhilaPlace)