Spiritualists and Spiritualism

By Barbara Franco | Public Nomination

Essay

The Philadelphia area became a center of Spiritualist activity in the mid-nineteenth century, appealing to radical Quakers reformers, who supported progressive ideals of racial and gender equality, individualism, progress, and scientific approaches, and to grieving families anxious to communicate with the spirits of departed loved ones. The First Association of Spiritualists of Philadelphia met in January 1852, making it the first in the country. By the 1870s, national conventions met annually, often in conjunction with women’s rights groups. Three local Spiritualist societies were reported in Philadelphia in 1871 as well as organized groups in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and southern New Jersey. Over time, spiritualism lost its appeal and adopted a more conventional organizational model, including ministers, but continued with local circles into the twenty-first century.

Beginning in the 1820s the writing of Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), an eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and mystic, attracted intellectuals seeking alternatives to the constrictive predestination of Calvinism and searching for a more universal religion. Swedenborg’s ideas of an “inner church,” communication with spirits, and harmony with nature directly influenced Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82) and the New England Transcendentalists, as well as other American intellectuals, writers, and artists. In self-induced trances through breath control, Swedenborg envisioned and described a complex afterlife that included an interim world of spirits and successive levels of heaven or hell. German physician Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) proposed that in a “mesmerized” hypnotic state magnetic forces could restore health. Animal magnetism gained popularity in the United States by the 1840s and some who awakened from trances reported visions of spirits. Andrew Jackson Davis (1826-1910) combined elements of Swedenborgianism and Mesmerism to promote his own American form of spiritualism based on individual spiritual progress through various levels of knowledge and the existence of a parallel spirit world that he named “Summerland.” After practicing magnetic healing in 1844-45, he published The Principles of Nature: Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind in 1847, based on his own self-described clairvoyant powers.

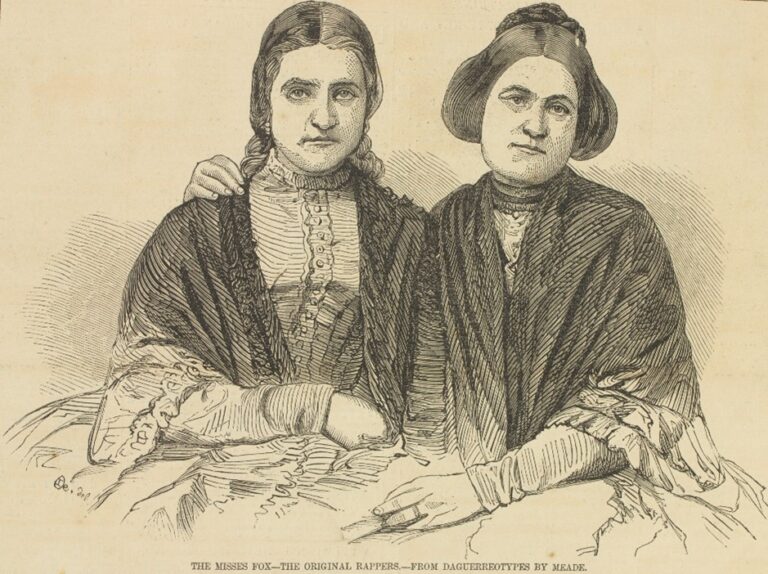

In 1848 Maggie (1833-93) and Kate (1837-92) Fox, two young sisters living near Rochester, New York, claimed to interpret rapping noises that they attributed to spirits. Davis enthusiastically wrote, “Behold, a living demonstration is born.” The success of the Fox sisters launched a Spiritualism movement that attracted both believers and skeptics to seances and demonstrations led by a growing number of mediums who offered to connect grieving families to deceased loved ones and share the wisdom of spirits through rapping noises, trance writing, spirit paintings, magnetic healing, and eventually physical materializations.

Radical Quakers involved in abolition and women’s rights were among the first to adopt and promote the Fox sisters. Isaac (1798-1872) and Amy Post (1802-89) of Rochester, New York, Hicksite Quakers involved in social reform movements, played a key early role in promoting the experience of the Fox sisters and the authenticity of spiritualism. The Posts undoubtedly influenced the adoption of spiritualism among Philadelphia’s radical Quaker community, and especially Dr. Henry Teas Child (1816-90), a prominent physician, abolitionist, and close associate of Lucretia Mott (1793-1880). Radical reformers and feminists in several planned communities in southern New Jersey-Vineland (Cumberland County), Ancora (Camden County), and Hammonton (Atlantic County)–also organized active Spiritualist societies.

Spiritualists in the Philadelphia Area

According to an account published in 1851, Philadelphia had more than fifty circles made up of “Presbyterians, Quakers, Unitarians, Baptists, Methodists, Come-outers, Infidels and Atheists.” Circles were formed with ten to eighteen individuals, often family or friends of both sexes, equally divided between masculine and feminine natures, corresponding to positive and negative. Meetings held in homes opened with vocal or instrumental music followed by readings on spiritual philosophy from Davis or other authors. Seated around a table, perfect harmony was necessary for the designated medium to establish contact. Spiritualists resisted any central ruling church body or creed; national, state, and even local societies provided only a voluntary association of autonomous individuals and groups. In addition to private and public circles, some societies rented or purchased buildings for lectures and operated educational Lyceums for children. Beginning in 1879 the First Association of Spiritualists held annual camp meetings near Neshaminy Falls in Bucks County. Spirit contacts progressed from simple rapping to written messages, and finally material apparitions. As demonstrations of materializations became more theatrical, seances attracted new audiences as well as critics.

From the beginning, Spiritualists invited skeptics to investigate the authenticity of spirit communications through scientific observations and experiments. In 1874 Philadelphia mediums Nelson and Jennie Holmes began presenting seances that included spirit materializations of Katie King and her father, supposed to be the pirate captain Henry Morgan. Henry Teas Child, his friend the utopian socialist Robert Dale Owen (1801-77), and other prominent Spiritualists at first endorsed the authenticity of the materializations, but they had to admit their deception when the young woman who portrayed Katie King published her confession in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Despite the evidence of fraud among some mediums, Spiritualism continued to maintain loyal followers. Philanthropist Henry Seybert (1801-83) left money to the University of Pennsylvania to scientifically investigate modern spiritualism, hoping to prove its authenticity. The Seybert Commission, consisting of prominent clergymen, doctors and scientists, nevertheless concluded in its 1887 report that there was no scientific evidence for spirit contacts.

Spiritualism lost its radical foundations as temperance and women’s rights advocates increasingly turned to mainstream Christianity for support in the twentieth century. The Church of Christ, Scientist, founded by Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910) in 1879, began to compete with Spiritualism among those seeking a new alternative faith. Some Spiritualists responded by adopting more orthodox practices such as ordained ministers, Sunday services, and camp meetings. Spiritualists continue to worship in various locations within the city and surrounding area, and in 2022 the National Spiritualist Association of Churches listed one affiliated church in Philadelphia and one in Westville, New Jersey.

Barbara Franco is an independent scholar focusing on nineteenth-century social and cultural history. She formerly served as executive director of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and founding director of the Gettysburg Seminary Ridge Museum. She is coauthor of Interpreting Religion at Museums and Historic Sites.

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.